I: Introduction

My commentary below is just a personal interpretation of the symbolism of the Buddha myth; furthermore, the focus here isn’t on the historical Buddha, of which little can be known for sure, but on the legendary narratives. I am neither a Buddhist, nor am I anywhere close to being an expert on the study of Buddhism. The following is just my thoughts on the meaning behind his legendary life story, for what they’re worth, so take it with a generous dose of salt.

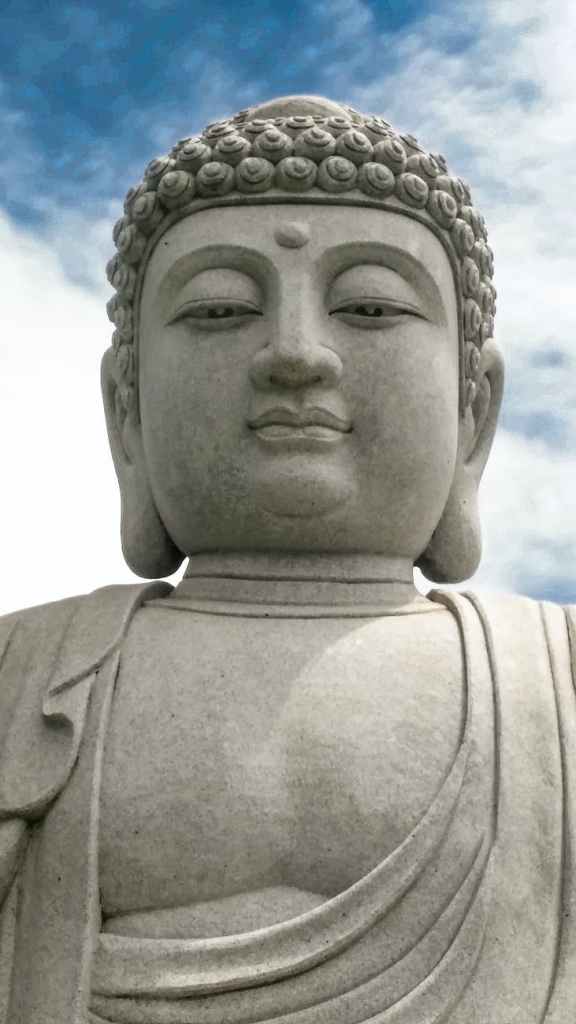

The Buddha was known by many names, including Shakyamuni, “the sage of the Shakyas.” The Shakya people had a small kingdom, Kapilavastu, just south of the Himalayas in India; this was around the sixth century BCE.

Kapilavastu was a peaceful kingdom ruled by King Suddhodana and Queen Maya. Later legend claims that the Buddha was born into a royal family (though modern scholars doubt this), which should give us some idea of the political agendas behind such legends. The close association thus assumed to exist between those of high birth and those who are spiritually advanced is another example of how religious traditionalism is used to justify and perpetuate class differences and authoritarianism.

II: Queen Maya

One full-moon night, Maya dreamed of a white elephant with six tusks coming down from the heavens and entering her womb from the right side, prophesying the birth of a great man. The white of the elephant suggests spiritual purity, the god Indra has such an elephant (the animal being seen as a symbol of greatness), and one has often seen wealthy men riding in howdahs on elephants; so we see again the association of high spirituality with a high social position.

Pregnant Maya left the king and returned to her parents’ home, as was the custom of the time. On the way, she stopped in a garden in a park in Lumbini. Here, among the beautiful flowers, she gave birth to the prince under a sal tree. He would be named Siddhartha (“the All-Successful One,” or “He Who Achieves His Aim”) Gautama.

Soon after Siddhartha’s birth, a wise hermit named Asita came from the mountains to the palace to congratulate the king and queen for their new child. Yet he was sad, because as an old man, Asita knew he’d never live to see the baby grow into the greatness he was destined to have: to be a king of kings, or to be a Buddha.

III: Joy and Sadness

Again, we see the association of spiritual greatness with regal nobility, a justification of the caste system that allows the rich to stay rich and keeps the poor in squalor. Asita’s sadness also reflects the dialectical relationship between happiness and sadness: a great child was born, but the hermit would never see that greatness come to fruition. One is reminded of Verse 58 in the Tao Te Ching: “Misery is what happiness rests upon./Happiness is what misery lurks beneath.”

Added to this juxtaposition of joy and sorrow was the death, only seven days after Siddhartha’s birth, of his mother, Queen Maya. Though he was too young to remember her, he in his great spiritual development was greatly affected by her loss. Maya is Sanskrit for “illusion.” Illusion dialectically gives birth to enlightenment. The brief flowering of the sal tree symbolizes impermanence, so this combined with her death emphasizes the association between birth, death, illusion, and impermanence. The young prince would have felt all this.

Not being able to have the Oedipally-desired mother, Lacan observed, is a lack giving rise to desire for anything to replace her, a replacement that never satisfies, the objet petit a. The prince, in his wisdom, knew he’d never have that satisfaction, so he’d soon learn to give up desiring altogether.

IV: Growing Up

He and his cousin, Devadatta, were skilled at archery. When the latter shot down a flying swan, though, the prince was full of sadness to see it in pain. Devadatta claimed it belonged to him, but Siddhartha, having pulled out the arrow and rubbing its wound to heal it, wanted it. They went to the court of a sage to decide what would happen to the animal. The sage, wisely knowing that the one who saves an animal has more right to it than the one who tries to kill it, favoured the prince, so it was his. Devadatta would resent this, and the cousins would be spiritual rivals later in life.

When the prince came of age, he wanted to know what the world outside his palace walls was like. His father, the king–worried that he would want to be a spiritual teacher rather than his successor to the throne–tried to distract him with indulgence in worldly pleasures: beautiful dancing girls, wealth and finery, etc. Siddhartha still wanted to go outside.

Here, instead of seeing the association between high spirituality and high social rank, we see the contradiction between the two. The prince would resolve this contradiction, to an extent, by marrying his cousin Yaśodhara and, by her, fathering a son, Rāhula; but he would still go outside.

V: His Four Trips Outside

On his first trip out, through the East Gate, he would see an old man. On his second trip, through the West Gate, he’d see a sick man. On his third, through the South Gate, he’d see a dead man’s funeral. This must have brought out feelings of his dead mother, his unattainable objet petit a.

Suffering is universal…especially for the poor.

On his fourth trip, out the North Gate, the prince saw something encouraging, for a change: he saw a holy man sitting in peace. This gave the prince hope that suffering can be ended…even in a world of poverty.

VI: Giving Up His Power

The contradiction between high social rank and high spiritual attainment is highlighted once again when we see the prince having made the Great Renunciation, giving up his position of regal power to help humanity and end suffering. Siddhartha’s decision to do this should be an inspiration to all in positions of political or financial power: give it up, and end class conflict. Sadly, far too few of them heed the message this inspiring renunciation gives us.

Siddhartha was twenty-nine years old when he chose to go from prince to mendicant, going from holy man to holy man for spiritual guidance, and practicing strict asceticism. None of the teachers had the answers he sought.

His asceticism grew more extreme; first, he ate only one grain of rice a day, then he stopped eating altogether. Five men became his disciples. It had been six years since he’d left the castle. His extreme self-denial was harming his physical health.

VII: From Suffering to Enlightenment

Just as Siddhartha’s ventures outside the castle walls showed him visions of increasing suffering, then a glimpse of holy inspiration, so would the increasing suffering he felt from his extreme asceticism lead to the holy inspiration of discovering the Middle Path.

The dialectical relationship between this increase of suffering, leading to greater spiritual awareness, can be compared to the points on a circular continuum that I’ve used the ouroboros to symbolize: the point of departure is the serpent’s biting head, the increasing suffering is movement along the length of its coiled body towards its bitten tail, and the enlightenment is a return to the biting head. I’ve written of the ouroboros as a symbol of the dialectical relationship between opposites (which meet where the serpent’s head bites its tail) in many other blog posts.

A girl named Sujata gave almost-dying Siddhartha some rice pudding and milk, and helped restore his health. His five followers, though, disappointed at his ‘weak resolve,’ left him.

VIII: Meditating Under the Bodhi Tree

Now better, he sat at the foot of the Bodhi Tree to begin meditating. He was determined not to get up until he’d attained enlightenment. This hard resolve of his is an interesting parallel to his previous, self-starving effort, with the crucial difference being one of success instead of near self-destruction. Of course, nirvana is a kind of destruction…that is, of an illusory self.

Mara the demon tried to tempt Siddhartha from finding enlightenment through pleasure (i.e., the devil’s three beautiful daughters) and through guilt (i.e., from having abandoned his kingdom). He resisted these temptations.

He was assailed with the temptations of Mara again, whose devils rained arrows on him; yet in his growing power, Siddhartha either transformed the arrows into flowers or had the arrows fly back at the devils. Turning arrows into flowers symbolizes the wise way to deal with hate: to turn it into love; one is reminded of Verse 197 in the Dhammapada: “Indeed we live very happily, not hating anyone among those who hate; among men who hate we live without hating anyone.” Also, there is Verse 5: “For hatred does not cease by hatred at any time: hatred ceases by love, this is an eternal rule.” The arrows flying back at the devils symbolize bad karma.

Mara claimed that only he could be the greatest, and that Siddhartha had no claim to greatness. Siddhartha responded by touching the earth, an appeal to the mother goddess, who acknowledged him as a great sage. Mara knew he lost.

IX: Becoming the Buddha

Finally, at the age of thirty-five, Siddhartha Gautama attained enlightenment. From now on, he would be known as Buddha (“the Enlightened One”), Shakyamuni (“the Sage of the Shakyas”), the World-Honoured-One, or Tathāgata (“the One Thus-gone”).

He now understood the Four Noble Truths: the universality of unhappiness in the world; the cause of unhappiness, being desire; the way to end unhappiness, being the extinguishment of desire; and the following of the Eightfold Path to end unhappiness.

He got up from the Bodhi Tree and went to Benares to teach others how to end suffering, for his compassion for all–those who didn’t know the Dharma–necessitated his helping them. Mara tried to tempt him away from sermonizing, too, but of course the demon failed.

X: His First Sermon

The Buddha found his five old followers who’d thought he’d given up on trying to find enlightenment. They quickly realized how wrong they were about him, and they became his disciples again. To them, he preached his first sermon, in the Deer Park in Benares.

He taught that one must avoid the extremes of indulgence in pleasure, on the one hand, and of self-mortification, or enduring extreme pain, on the other. Doing neither is useful or worthwhile. The Middle Path, avoiding the extremes, is useful and worthwhile. He also taught the Four Noble Truths.

One must follow the Noble Eightfold Path, in which each part builds on and reinforces the preceding and succeeding parts: right understanding, right intention, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

One cannot have the right intentions without the right belief system, or understanding of the world, as a foundation for those intentions. Of all the good deeds one can do, speaking the right way (i.e., with kindness and honesty) should be the easiest. Good deeds should lead naturally to doing honest work (i.e., non-exploitative work, and not cheating people).

Right effort (i.e., resisting temptations before they arise, abandoning sin when it has arisen; also, arousing and maintaining wholesome states of mind) should grow from this living of a good life, and in turn that effort should lead to right mindfulness (i.e., always keeping one’s mind on the goal of liberation). Right concentration, that is, meditation, is an extension of mindfulness to every second of one’s thoughts.

XI: No Gods, No Self

Since the gods are part of the phenomenological world of pain and suffering, they cannot help us attain nirvana, which is a state of no-thing-ness, of a fluid, ever-changing reality that is unlike any perceived ‘fixed’ state of being. Our attachment to previous forms of being, wishing them never to go away, is what causes our suffering.

Without the aid of the gods, we must rely on ourselves. As daunting a task as this is, to attain enlightenment on our own, we nonetheless have Three Jewels to take refuge in: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

When one speaks of ‘self’-reliance, though, one must use the word self with caution; for the Buddha taught that there is no self (anattā, or anātman), in direct contrast with the Hindu concept of one’s eternal soul, Atman, being one and the same as Brahman, or the eternal oneness behind the whole universe. If all is impermanent (anicca), there can be no soul; karma is what binds people to the cycle of reincarnation.

How can one reconcile the contradiction between the Hindu conception of Atman with the Buddhist concept of anātman? I use the dialectical relationship between opposites to do that. Impermanence is, paradoxically, the one permanent reality. Self and other are unified, as I see them; Atman and Brahman are one. Brahman is an infinite ocean of perpetual change, ever flowing from one temporary state to another, from one dialectical opposite to the other, and we are a part of that endless flowing, though we think we each have a self. Lacan recognized what a lie the notion of a fixed, permanent self is, in our experience of the mirror stage.

In any case, the Buddha was not interested in speculation about theological or philosophical matters; he just wanted to end suffering, and thus to focus on what would help end suffering. These issues were recorded in the Lesser Mālunkyāputta Sutra.

XII: The Fire Serpent

He went to the Kingdom of Magadha, where he stayed overnight in the hall of the sacred fire of Agni, worshipped by the three Kasyapa brothers. There, a fire snake emerged to attack him, but he used his radiant power to charm, calm, and defeat it. The three brothers were so impressed (and repentant that they’d tried to have the Buddha killed) that they and their many disciples joined the Sangha. (The story is represented on a fragment of a stone slab from Gandhara.) He would teach them the Fire Sermon.

The vanquishing of the fire serpent symbolizes the defeating of the fires of desire. In this story, I also see, in the calming of the snake, an illustrative example of what in psychoanalytic circles is Bion‘s theory of containment. Normally something a mother does to pacify her agitated baby, or what a psychotherapist does for his or her psychotic analysand, containment involves receiving the agitation of a distressed person (this agitation and distress being known as the contained) and being a container for it. One detoxifies the contained distress and returns it to the upset person, but it’s now in a tolerable, acceptable form. (See here for more on Bion and other psychoanalytic ideas.)

The Buddha made himself the container of the fire snake’s ferocity (the contained). He used what Bion called alpha function to soothe and calm the snake. The ‘heart of the Buddha,’ that is, his calm, loving, compassionate way replaced the ferocity with calmness and returned this now-soothing energy to the serpent. This kind of soothing and pacifying, reflected in the Christian tradition by the notion of ‘turning the other cheek,’ is the ideal way to deal with the hostility of other people. If only it weren’t so difficult to do…

XIII: Spreading His Message

The Buddha’s message spread so far that it was received by followers of all social classes, from the poorest and hungriest to the richest of kings, including King Bimbisara of Magadha, who donated a garden of squirrels to the Sangha, the Bamboo Grove Monastery.

The Buddha returned to the Shakyas to see his father, King Suddhodana, his wife, Yaśodharā, and his son, Rāhula. The king had hoped he’d be dressed better, but the Buddha knew he didn’t need fine clothing. Purity of heart is more important. Soon, all the Shakyas became Buddhists.

These incidents, including the donation of the Prince Jeta Monastery through the (unnecessary) covering of the ground with thousands of gold coins, show how the Buddha’s message of love, compassion, and conquering of desire can win over even the wealthy and powerful.

XIV: The Three Poisons

Still, conquering our passions is never easy, even for committed monks. The three poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion must be constantly guarded against; and even monks can miss the mark, as the Buddha noted in the quarrel among the monks of Kosambi, which even he couldn’t resolve (over a fairly minor problem, unclean water that mosquitoes might breed in), and threatened a rending asunder of the congregation.

Suffering isn’t caused only by wanting to keep things we cannot keep (greed) because of the reality of impermanence; it’s also caused by not accepting the unpleasant things that must be (hatred), even if just temporarily. The delusion behind all of this is the belief in a permanent pleasure and permanent non-existence of pain. All things, both good and bad, flow to us and away from us, like ocean waves.

XV: Devadatta

Speaking of sinful Buddhist followers, we mustn’t forget the Buddha’s envious cousin, Devadatta, who as a fellow Buddhist monk formed a splinter group to rival the Sangha. According to the Theravada Vinaya, Devadatta persuaded Prince Ajātasattu to have his father, King Bimbisara, killed (or jailed?); then he hired mercenaries to kill the Buddha.

But the mercenaries couldn’t bring themselves to do so horrible a deed, and they joined the Sangha instead. Devadatta made other attempts on the Buddha’s life, such as throwing a huge rock from up high on a mountain to crush him (it missed), and releasing an intoxicated elephant to trample him (as with the fire serpent, the Buddha used his powers of love and compassion to tame the elephant).

Devadatta eventually repented of his sin, but karma would have its way, and when he approached the Buddha, the earth opened up and sucked him into the Niraya Hell.

XVI: Angulimāla

There are sinners who pretend to be good, like Devadatta; then there are those who are unabashedly bad, like Angulimāla, a robber who murdered hundreds, having cut off a finger from each victim to wear on a necklace (hence, his name).

When he encountered the Buddha, Angulimāla had already murdered 999 victims and was craving his thousandth, to fulfill a demand made by his old teacher for a thousand fingers. So wicked had Angulimāla become that he was actually considering murdering his own mother! Karma would never support such a crime, hence the Buddha’s intervention.

When he appeared on the road through a forest in Kosala, Angulimāla began chasing after him. Strangely, the killer was running as fast as he could, with his sword drawn, but the Buddha was just calmly walking. Even more strangely, instead of catching up with the Buddha, Angulimāla found the distance between himself and his prey lengthening!

The killer yelled at the Buddha to stop, to which he replied that he’d already stopped, and it was his pursuer who needed to stop. The killer repented and became a monk, who then had to endure the wrath of the families and friends of all of his murder victims; the Buddha told him to endure their hatred with patience, for such was his karmic burden.

This story demonstrates the superiority of calm over the passions; it also teaches how even the worst of people can be redeemed and made good.

XVII: The Buddha Enters Parinirvana

The Buddha spread his message for almost fifty years before finally falling ill and dying at about the age of eighty. He was going from Rajagaha to Savatthi. He reached a forest bordering Kusinara and rested between two large sala trees.

His disciple, Ananda, made a bed for him under the shade of the two trees. Subhadda, the Brahmin, came to see him, and he became the Buddha’s last disciple. He lay on the bed, reclining.

As he lay dying, the Buddha consoled his mourning disciples by saying that all things arise and pass away. “All compound things are transitory,” he said. “Seek out your liberation with diligence.” Then he died.

He went into the state of parinirvana, the end of his last physical life and into nirvana. Twentieth century scholars gave his dates as 563 BCE to 483 BCE, but recent scholarship considers the following dates as more accurate: from about 480 to about 400 BCE.

XVIII: Prodigal Sons

There is a story in the Lotus Sutra, about a young man who runs away from home, then, destitute, accidentally finds himself returned to the city of his (unrecognized) father, now a wealthy old man who recognizes his son and wants to ensure the boy inherits his wealth when he dies. Christians sometimes misinterpret this story, thinking that when the father gives his son work, he is making the boy do penance for his former unfilial ways. Part of the motive for such a misinterpretation is to present the forgiveness of the father in the Christian parable as proof of the ‘superiority’ of Christianity over Buddhism. Apparently, only Christianity offers grace; other religions require atonement.

The father in the Buddhist story, however, already forgives his son, and would eagerly have him back; but the boy, in his shame and impoverishment, would never accept being taken in as the son of such a rich man. The father accepts this mistaken feeling of his son, and employs him only to ensure that the boy is always nearby. He will tell his son the truth when the boy is ready to hear it. He also goes over to his son in filthy clothes and works with him.

When the son eventually learns who the rich old man really is, and that he is to inherit his father’s wealth, he is overjoyed to receive so unexpected a fortune, one unearned and given as a free gift. His job of cleaning away dung was not penance, but just something he did because of his inability to comprehend that he already had his father’s favour.

The father represents the Buddha as understood in the Mahayana tradition; the son represents those Theravada arhats who would never believe themselves capable of attaining Buddhahood. The purpose of the story is to tell Theravada Buddhists that, while they may continue practicing Buddhism in their usual way, they may become Buddhas just as Siddhartha did.

In an extended sense, this story can be interpreted to mean that we all have potential Buddha-nature. The Mahayana tradition sees no distinction between nirvana and samsara, two opposites that I would consider dialectical in nature. These things put together can be seen as a kind of grace, encouraging us, as the dying Buddha advised us, to seek our liberation with diligence.

A part of the life of the Buddha. Thank you 😊

The mythical part, anyway. Thanks for reading! 🙂

You are welcome!