In this analysis, I’ll be focusing on the George Lucas films, not the Disney debacle (my reasons for this are given below). As inferior as the prequels were to the trilogy of undeniably good films, at least they were a part of Lucas’s vision, not merely a grab for money.

I am saddened by the fact that, in all likelihood, I won’t live to see Lucas’s original idea for the sequel trilogy presented on the screen. All I can do is speculate and use my imagination as to how the Whills are in the drivers’ seats, controlling everything, behind every life form.

Nonetheless, there is enough material in Lucas’s six films to explore how he weaved a narrative–as clunky as his dialogue often was–to combine myth, mysticism, film lore, and (for me, the most exciting part) anti-imperialism.

Here are some famous quotes…and a few infamous ones:

Star Wars (1977)

“The Force is what gives a Jedi his power. It is an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us; it binds the galaxy together.” –Ben (Obi-Wan) Kenobi, to Luke

Luke: I can’t get involved! I’ve got work to do! It’s not that I like the Empire, I hate it, but there’s nothing I can do about it right now. It’s such a long way from here.

Obi-Wan: That’s your uncle talking.

Motti: Any attack made by the Rebels against this station would be a useless gesture, no matter what technical data they’ve obtained. This station is now the ultimate power in the universe! I suggest we use it.

Vader: Don’t be too proud of this technological terror you’ve constructed. The ability to destroy a planet is insignificant next to the power of the Force.

Motti: Don’t try to frighten us with your sorcerer’s ways, Lord Vader. [Vader walks toward Motti, then slowly raises his hand] Your sad devotion to that ancient religion has not helped you conjure up the stolen data tapes or given you clairvoyance enough to find the Rebels’ hidden fortr––[grasps his throat as if he is being choked]

Vader: I find your lack of faith disturbing.

Tarkin: Princess Leia, before your execution, I would like you to be my guest at a ceremony that will make this battle station operational. No star system will dare oppose the Emperor now.

Leia: The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.

Obi-Wan: Remember, a Jedi can feel the Force flowing through him.

Luke: You mean it controls your actions?

Obi-Wan: Partially, but it also obeys your commands.

“Don’t underestimate the Force.” –Vader, to Tarkin

Vader: I’ve been waiting for you, Obi-Wan. We meet again at last. The circle is now complete. When I left you, I was but the learner. Now I am the Master.

Obi-Wan: Only a master of evil, Darth.

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Gen. Maximilian Veers: My Lord, the fleet has moved out of lightspeed. Com-Scan has detected an energy field protecting an area of the sixth planet of the Hoth system. The field is strong enough to deflect any bombardment.

Vader: The Rebels are alerted to our presence. Admiral Ozzel came out of lightspeed too close to the system.

Veers: He felt surprise was wiser–

Vader: [angrily] He is as clumsy as he is stupid. General, prepare your troops for a surface attack.

Veers: Yes, my Lord. [bows and leaves quickly][Darth Vader turns to a nearby screen and calls up Admiral Kendel Ozzel and Captain Firmus Piett.]

Ozzel: Lord Vader, the fleet has moved out of lightspeed and we’re preparing to– [begins choking]

Vader: You have failed me for the last time, Admiral.

The Emperor: The Force is strong with him. The son of Skywalker must not become a Jedi.

Vader: If he could be turned, he would become a powerful ally.

The Emperor: [intrigued] Yes… He would be a great asset. Can it be done?

Vader: He will join us or die, master.

Han Solo: You like me because I’m a scoundrel. There aren’t enough scoundrels in your life.

Princess Leia: I happen to like nice men.

Han Solo: I’m a nice man.

Princess Leia: No, you’re not…[they kiss]

“Yes, a Jedi’s strength flows from the Force. But beware of the dark side. Anger, fear, aggression; the dark side of the Force are they. Easily they flow, quick to join you in a fight. If once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your destiny, consume you it will, as it did Obi-Wan’s apprentice.” –Yoda, to Luke

Luke, having seen his X-wing sunk into the bog: Oh, no! We’ll never get it out now!

Yoda: So certain, are you? Always with you, it cannot be done. Hear you nothing that I say?

Luke: Master, moving stones around is one thing, but this is… totally different!

Yoda: No! No different! Only different in your mind. You must unlearn what you have learned.

Luke: All right, I’ll give it a try.

Yoda: No! Try not. Do… or do not. There is no try.[Luke tries to use the Force to levitate his X-wing out of the bog, but fails in his attempt.]

Luke: I can’t. It’s too big.

Yoda: Size matters not. Look at me. Judge me by my size, do you? Hmm? Hmm. And where you should not. For my ally is the Force, and a powerful ally it is. Life creates it, makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. You must feel the Force around you; here, between you, me, the tree, the rock, everywhere, yes. Even between the land and the ship.

Luke: You want the impossible. [sees Yoda use the Force to levitate the X-wing out of the bog and gets flustered when he does it] I don’t… I don’t believe it!

Yoda: That is why you fail.

Darth Vader, after choking Captain Needa to death: Apology accepted, Captain Needa.

Luke: I feel the Force.

Obi-Wan: But you cannot control it. This is a dangerous time for you, when you will be tempted by the dark side of the Force.

“Only a fully trained Jedi Knight with the Force as his ally will conquer Vader and his Emperor. If you end your training now, if you choose the quick and easy path as Vader did, you will become an agent of evil.” –Yoda, to Luke

“Luke. Don’t give in to hate. That leads to the dark side.” –Obi-Wan

Leia Organa: I love you.

Han Solo: I know.

“The force is with you, young Skywalker, but you are not a Jedi yet.” –Vader

Vader: If only you knew the power of the dark side. Obi-Wan never told you what happened to your father.

Luke: He told me enough. He told me you killed him.

Vader: No. I am your father.

Luke: [shocked] No. No. That’s not true! That’s impossible!

Vader: Search your feelings; you know it to be true!

Luke: NO!!! NO!!!

Vader: Luke, you can destroy the Emperor. He has foreseen this. It is your destiny. Join me, and together, we can rule the galaxy as father and son! Come with me. It is the only way. [Luke lets go of the projection and falls into the shaft]

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Luke: Obi-Wan. Why didn’t you tell me? You told me Vader betrayed and murdered my father.

Obi-Wan: Your father was seduced by the dark side of the Force. He ceased to be Anakin Skywalker and became Darth Vader. When that happened, the good man who was your father was destroyed. So what I told you was true, from a certain point of view.

Luke: [incredulously] A certain point of view?

Obi-Wan: Luke, you’re going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view. Anakin was a good friend. When I first knew him, your father was already a great pilot. But I was amazed how strongly the Force was with him. I took it upon myself to train him as a Jedi. I thought that I could instruct him just as well as Yoda. I was wrong.

Luke: There is still good in him.

Obi-Wan: He’s more machine now than man. Twisted and evil.

Leia: But why must you confront him?

Luke: Because there is good in him, I’ve felt it. He won’t turn me over to the Emperor. I can save him; I can turn him back to the good side. I have to try. [kisses Leia on the cheek, then leaves]

Luke: Search your feelings, father. You can’t do this. I feel the conflict within you. Let go of your hate.

Vader: It is… too late for me, son. The Emperor will show you the true nature of the Force. He is your master now.

Luke: [resigned] Then my father is truly dead.

“I’m looking forward to completing your training. In time, you will call me ‘Master’.” –the Emperor, to Luke

“It’s a trap!” –Admiral Ackbar

The Emperor: Come, boy, see for yourself. From here, you will witness the final destruction of the Alliance and the end of your insignificant rebellion. [Luke’s eyes go to his lightsabre] You want this, don’t you? The hate is swelling in you now. Take your Jedi weapon. Use it. I am unarmed. Strike me down with it. Give in to your anger. With each passing moment you make yourself more my servant.

Luke: No.

The Emperor: It is unavoidable. It is your destiny. You, like your father, are now mine.

Stormtrooper: Don’t move!

Han Solo, glances nervously at Leia…who subtly reveals the blaster hidden at her side: I love you.

Princess Leia: [smiles] I know.

The Phantom Menace (1999)

“Exsqueeze me…” –Jar Jar Binks

Maul: At last we will reveal ourselves to the Jedi. At last we will have revenge.

Sidious: You have been well trained, my young apprentice. They will be no match for you.

“How wude!” –Jar Jar Binks

“Yippie!” –Anakin

Palpatine: [Whispering to Queen Amidala] Enter the bureaucrats, the true rulers of the Republic. And on the payroll of the Trade Federation, I might add. This is where Chancellor Valorum’s strength will disappear.

Valorum: The point is conceded. Will you defer your motion to allow a commission to explore the validity of your accusations?

Padmé: I will not defer. I’ve come before you to resolve this attack on our sovereignty now! I was not elected to watch my people suffer and die while you discuss this invasion in a committee! If this body is not capable of action, I suggest new leadership is needed. I move for a vote of no confidence in Chancellor Valorum’s leadership. [The Senators begin arguing over Queen Amidala’s decision, as Valorum sits down, stunned]

Mas Amedda: ORDER!!

Palpatine: Now they will elect a new Chancellor, a strong Chancellor. One who will not let our tragedy continue.

Mace Windu, after Darth Maul’s defeat: There’s no doubt the mysterious warrior was a Sith.

Yoda: Always two, there are. No more, no less. A master and an apprentice.

Windu: But which one was destroyed, the master or the apprentice?

Attack of the Clones (2002)

“Why do I get the feeling you’re going to be the death of me?” –Obi-Wan, to Anakin

Barfly: You wanna buy some death sticks?

Obi-Wan: [executes a Jedi mind trick] You don’t want to sell me death sticks.

Barfly: I don’t wanna sell you death sticks.

Obi-Wan: You want to go home and rethink your life.

Barfly: I wanna go home and rethink my life. [leaves]

“I see you becoming the greatest of all the Jedi, Anakin. Even more powerful than Master Yoda.” –Palpatine

“Attachment is forbidden. Possession is forbidden. Compassion, which I would define as unconditional love, is essential to a Jedi’s life. So you might say, that we are encouraged to love.” –Anakin

“I don’t like sand. It’s coarse and rough and irritating and it gets everywhere. Not like here. Here everything is soft and smooth.” –Anakin, to Padmé

Mas Amedda: This is a crisis. The Senate must vote the Chancellor emergency powers. He can then approve the creation of an army.

Palpatine: But what Senator would have the courage to propose such a radical amendment?

Amedda: If only…Senator Amidala were here.

“Victory? Victory, you say? Master Obi-Wan, not victory. The shroud of the dark side has fallen. Begun, the Clone War has!” –Yoda

Revenge of the Sith (2005)

“Chancellor Palpatine, Sith Lords are our speciality.” –Obi-Wan

Anakin: My powers have doubled since the last time we met, Count.

Dooku: Good. Twice the pride, double the fall.

Palpatine: Have you ever heard the Tragedy of Darth Plagueis the Wise?

Anakin: No.

Palpatine: I thought not. It’s not a story the Jedi would tell you. It’s a Sith legend. Darth Plagueis was a Dark Lord of the Sith so powerful and so wise, he could use the Force to influence the midi-chlorians to create… life. He had such a knowledge of the dark side, he could even keep the ones he cared about… from dying.

Anakin: He could actually… save people from death?

Palpatine: The dark side of the Force is a pathway to many abilities some consider to be unnatural.

Anakin: What happened to him?

Palpatine: He became so powerful, the only thing he was afraid of was losing his power…which, eventually of course, he did. Unfortunately, he taught his apprentice everything he knew, then his apprentice killed him in his sleep. Ironic. He could save others from death… but not himself.

Anakin: Is it possible to learn this power?

Palpatine: Not from a Jedi.

“POWER!!!! UNLIMITED POWER!!!!” –Palpatine, then sending Windu flying out the window to his death

Anakin: I pledge myself… to your teachings.

Sidious: Good. Good… The Force is strong with you. A powerful Sith, you will become. Henceforth, you shall be known as Darth…Vader.

Palpatine: The remaining Jedi will be hunted down and defeated. [applause] The attempt on my life has left me scarred and deformed. But, I assure you, my resolve has never been stronger. [applause] In order to ensure our security and continuing stability, the Republic will be reorganized into the first Galactic Empire, for a safe and secure society. [the Senators cheer]

Padmé: So this is how liberty dies… with thunderous applause.

Vader: You turned her against me!

Obi-Wan: You have done that yourself!

Vader: YOU WILL NOT TAKE HER FROM ME!!!

Obi-Wan: Your anger and your lust for power have already done that. You have allowed this Dark Lord to twist your mind, until now- now, you have become the very thing you swore to destroy.

Vader: Don’t lecture me, Obi-Wan. I see through the lies of the Jedi. I do not fear the Dark Side as you do! I have brought peace, freedom, justice, and security to my new empire!

Obi-Wan: Your new empire?!

Vader: Don’t make me kill you.

Obi-Wan: Anakin, my allegiance is to the Republic, to democracy!

Vader: If you’re not with me, then you’re my enemy!

Obi-Wan: Only a Sith deals in absolutes. I will do what I must.

Vader: You will try.

“It’s over, Anakin! I have the high ground!” –Obi-Wan

[Obi-Wan Kenobi has cut off Vader’s legs and part of his remaining good arm on one of Mustafar’s higher grounds. Vader is struggling near the lava river]Obi-Wan: [anguished] You were the chosen one! It was said that you would destroy the Sith, not join them! Bring balance to the Force, not leave it in darkness! [picks up Anakin Skywalker’s lightsaber]

Vader: I HATE YOU!!!

Obi-Wan: You were my brother, Anakin. I loved you. [leaves as Vader, now too close to the lava river, catches on fire.]

“NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!” –Vader, after realizing he’s killed Padmé

Yoda: An old friend has learned the path to immortality. One who has returned from the netherworld of the Force… Your old master.

Obi-Wan: [surprised] Qui-Gon?!

Yoda: How to commune with him, I will teach you.

As my ordering of the above quotes indicates, I’m going through these films in the order they were made, rather than their order in terms of episodes. I’m doing this because, first, the above represents the order in which my generation and I experienced them, second, this is the order in which all the plot elements and characters were introduced for us, and third, anyone who hates the prequels so much that he or she doesn’t want to see them dignified with an analysis won’t have to scroll down to the good movies.

Star Wars

I’m also going by the original titles of the films, as you can see, rather than enumerating the “episodes.” It’s a nostalgia thing, as is my reason for giving minimal approval to the changes Lucas made to the original trilogy, most of which–in my opinion, at least–were unnecessary, self-indulgent, and even irritating at times.

Though the story takes place “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away,” its relevance to so much of what has happened in our world, up until now, shows the Unities of Time, of Space, and of Action, as I’ve described them elsewhere. These are universal themes, happening everywhere and at all times.

The opening crawl says, “It is a period of civil war.” Civil war, among the stars of the galaxy? By ‘civil,’ this means that members of the imperial senate are among those rebelling against the evil Galactic Empire. It’s a revolution from within, hence it’s a ‘civil war.’

Princess Leia claims she’s a member of the imperial senate on a diplomatic mission, when she’s actually behind the stealing of the Death Star plans. Later in the film, Commander Tagge, during a meeting of the imperial big brass on the Death Star, says “the rebellion will continue to gain a support in the imperial senate…”. The rebels are to a great extent made up of former members of the Empire…and what should we make of the Empire?

Note how they’re all Nordic-looking white men…not one of them is an alien, nor are any of them even non-white. We hear either British or American accents…or in the case of Darth Vader’s voice, the Transatlantic accent. The Galactic Empire thus can easily be seen to represent the Anglo-American imperialism of the past several hundred years.

Those dissidents who have left the Empire to join the rebellion are an inspiration to all of us living in the West, those who hate imperialism and late stage, neoliberal capitalism. It isn’t enough to hate the perpetrators of modern evils: we must fight them.

Fight the empire.

Granted, no one ever said it would be easy to fight them. That opening shot, of the tiny Tantive IV being chased and shot at by that huge Star Destroyer, coming from and dominating the top of the screen, establishes and emphasizes just how formidable an enemy the Empire is. Similarly, we in today’s world know who we’re up against, with not only a multi-billion-dollar funded American/NATO military, militarized cops, and their vastly superior technology, but also a trans-national corporate media that lulls us into submission.

Princess Leia’s iconic hairstyle, with its ‘cinnamon buns,’ was at least in part inspired by those of some of the Mexican women, called soldaderas, who fought in the Mexican Revolution. Darth Vader’s costuming, and that of the Jedi Knights, were inspired by that of the samurai, redolent of old, Japanese feudal times; for as benign as the Jedi are, they nonetheless represent a dogmatic, stodgy, conservative way of thinking that lends itself, despite the Jedi’s best intentions, to the authoritarianism of the Republic-turned-Empire.

Indeed, the Galactic Republic was always corrupt to some extent at least (more on that in the analyses of the prequels below); but in the emergence of the Empire, we see that corruption transforming into a kind of fascism. Before the rise of Naziism, the Weimar Republic was seen as a similarly corrupt democracy, hated by the German right and left. The Stormtroopers, whose name reminds us of the Sturmabteilung, wear uniforms that, appropriately, make them look like skeletons. Vader’s skull-like mask reinforces the Empire’s association with death. (Yes, note how masks represent conformity and hide individuality!)

R2-D2 and C-3PO, the only comic relief the franchise ever needed (Sorry, Jar Jar and BB-8), were inspired by two peasants from Akira Kurosawa‘s Hidden Fortress, as was so much of this movie. The first of these two ‘droids is the film’s MacGuffin, in its carrying of the Death Star plans to Tatooine.

In deleted scenes, Luke sees the Star Destroyer and rebel cruiser from his binoculars, then tells his friends, Deak, Windy, Fixer, and Camie, about it (see also Lucas, pages 16-19). Luke has had thoughts of joining the academy, since living on Tatooine is boring and depressing; but his friend Biggs tells him he’s leaving the Empire and joining the rebellion (Lucas, pages 24-27). This revelation gives Luke an important opportunity to begin questioning authority.

[In the deleted scene (link above) with Biggs and Luke, unfortunately Biggs says the Empire are starting to “nationalize” commerce; whereas in Lucas’s novelization, he says “they’re starting to imperialize commerce” (Lucas, page 26, my emphasis), which makes much more sense. How does one “nationalize” commerce in the context of “the central systems”? Also, nationalization isn’t exactly in keeping with imperialism.]

The contrast between feisty R2-D2 and polite and proper C-3PO is striking: the former defies authority, while the latter defers to it, except when the latter has no choice but to defy it. This contrast is emphasized when the two ‘droids part ways in the desert sands of Tatooine.

No analysis of Star Wars is complete without a discussion of Joseph Campbell‘s notion of the Hero’s Journey. Luke’s journey begins with his boring, ordinary world on Tatooine, the status quo. His Uncle Owen won’t let him leave and join the academy, rationalizing that he doesn’t yet have enough staff to replace Luke to work on the vaporators on his moisture farm; actually, Owen, knowing the fate of Luke’s father, doesn’t want the boy to suffer the same fate by getting involved in the conflict between the Empire and the rebels.

Luke’s call to adventure comes when he plays a fragment of a recording by Leia, who needs the help of Obi-Wan Kenobi. The boy is intrigued by two things in this recording: he recognizes the name Kenobi, wondering if she’s referring to old Ben Kenobi; Luke also notes how beautiful she is, not knowing she’s his twin sister (Did Lucas know she was his twin sister from the beginning? Some of us have our doubts about that, if you’ll indulge a little understatement on my part.).

Having tricked Luke into removing a restraining bolt attached to its side, R2-D2 sneaks away in search of Obi-Wan. Luke and Threepio chase after the twittering little ‘droid, only to be attacked by Sand People. Then Kenobi comes to rescue them, this moment being Luke’s meeting the mentor/supernatural aid.

In Kenobi’s home, two subjects under discussion between him and Luke are merged, one that has been of major emotional importance to the boy, and one that will be of major importance for the rest of his life: they are, respectively, his father and the Force. A mystery from Luke’s past, and a mystery to be unravelled in his future.

What’s particularly interesting about this juxtaposition of his father and the Force is that both have been divided into good and bad sides, though of course Luke doesn’t yet realize it. When Ben says, “Vader was seduced by the Dark Side of the Force,” Luke takes note only of, “the Force.”

Saying that Vader “betrayed and murdered” Luke’s father, instead of telling him what we all now know, the ret-con that Vader is his father, represents psychological splitting: Anakin is the good father, and Vader is the bad father. In fact, ‘Darth Vader’ is a pun on ‘dark father,’ or perhaps ‘dearth’ or ‘death (of the) father.’ Furthermore, ‘Vader’ can be seen as a near-homographic pun on the German word for ‘father’…Vater, which is appropriate, given the (unfortunate) stereotypical German association with fascism, and the Empire’s association with Naziism.

Just as there’s a duality in Luke’s father, so is there a duality in the Force; and while this film focuses on the dark side of Luke’s father (though Vader isn’t yet known to be him…and again, Lucas did not yet ‘know’ until after rewrites of Leigh Brackett‘s draft of The Empire Strikes Back), so does it focus on the good side of the Force.

…and what are we to make of this “ancient religion”? The mystical energy field has been compared to such ideas as the Chinese concept of ch’i, a knowledge of which helps the martial artist and samurai, to whom the Jedi can be compared. If one were religious, one might compare the Force to God, and its dark side to the Devil.

In order to defeat so intimidating an enemy as empire (be it the Galactic Empire of the Star Wars saga, or in our world, today’s US/NATO empire), one may find it helpful, at least in strengthening one’s sense of hope, to believe in some kind of Higher Power. For some, that might be God, the Tao, ch’i, or Brahman, as the Force can be seen to represent.

For me, the Force represents a kind of dialectical monism, the light and dark sides of which are sublated into the “balance” that is hoped for in the prequels. We Marxists, even though we’re generally not religious, can see the dialectical resolving of contradictions in history and economic systems as being symbolized by these yin-and-yang-like sides of the Force.

One interesting point made by Kenobi, in his description of the Force, is that it is “created by all living things,” rather than having created all life. This reversal is crucial in understanding how the Force is unlike any god. It’s useful for atheistic Marxists, too, who in our struggle against today’s imperialism, believe in dialectical materialism, in which the material world, and its dialectical contradictions, come first…then ideas come from the physical (i.e., through the brain). This conception is opposed to the Hegelian idea coming first (i.e., the Spirit), and physicality is supposed to grow from ideas.

So even if we’re atheists, we can derive hope from the dialectical materialist unfolding of history gradually resolving the contradictions of today and ending imperialism. This hope can give us the strength and resolve to carry on fighting our empire today, just as the rebels hope the Force will be with them. Even Han Solo, who doesn’t believe in the Force, uses its power, if only unconsciously.

We can also find inspiration in the Hero’s Journey, all the while understanding that it is no easy path to go on. Luke himself goes through his own refusal of the call when he tells Ben that he “can’t get involved.” Only the stormtroopers’ killing of his Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru will radicalize him into going with Ben to Alderaan and learning the ways of the Force.

This radicalizing of Luke is interesting in itself. During the “War on Terror,” we in the West have been propagandized into believing that “Islamists” are just crazed fanatics driven to violence by their ‘backward’ religion, rather than by such things as drone strikes from imperialists that kill Muslims’ families, thus radicalizing them, as Luke as been.

That Tatooine is a desert planet, symbolic of Third Word poverty, is significant. That desert poverty makes it easy to compare to life in the Middle East and north Africa, whose populations have been oppressed by Western imperialism (starting with the British and French empires, then Zionism and American neocons) for decades and decades. Recall that Lucas filmed the Tatooine scenes in Tunisia.

The killing of Luke’s aunt and uncle, pushing him to join Ben and learn how to be a Jedi, means that Luke is crossing the first threshold and beginning his hero’s journey. Those of the imperialist mentality would say Luke is becoming a terrorist…well, when hearing that, just consider the source.

The poverty and want of Tatooine, a planet among those in the Outer Rim (an area whose very name tells us already just how marginalized it is), indicates the economic aspect of oppression in the galaxy. The Empire in this context should be seen to symbolize the bourgeois state.

The role of any government, properly understood, is to represent and protect the interests of one class at the expense of the others. Coruscant–a planet that is one big city all over (a city of flying cars and night lights that visually remind us of the Los Angeles of Blade Runner), and that is the seat of the galactic state (in either its republican or imperialistic form)–is representative of the First World, with all of its wealth and privilege. The contrast of Coruscant against such desolate planets as Tatooine and Hoth should help us recognize the state in the Star Wars saga as the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.

Along with the desolation of Tatooine is the sense of alienation felt among its inhabitants. The aggression of the Sand People, gangsters like Jabba the Hutt, and the ruffians in the Mos Eisley cantina are indicative of such social estrangement as caused by the Galactic Empire. There’s so much needless fighting among them, a hostility that, if channeled properly, could be directed at the Empire instead.

Macho Han Solo, a cowboy without a hat, is yet another example of the “I’m alright, Jack” kind of rugged individualism in a world where solidarity against the Empire is needed far more. A deleted scene shows him with his arm around a pretty girl whom he calls “Sweetheart” when she leaves so he can meet Luke and Ben. Han’s involvement with the rebels, led by another “sweetheart,” will make a much-needed change in his character.

But for now, we just have the cocky he-man…so much so that, as a nod to all of us who saw the original version of this film, we can say that Greedo never fired a single shot before Han blew him away. Han, at this point in his life, wasn’t meant to be a good role model for children.

Another point needs to be made about Mos Eisley spaceport, as it was originally conceived: it originally had far fewer people, aliens, etc. That was the point–it was a lonely place where anyone trying to hide from the Empire could lie low and hope not to be apprehended. Adding all that CGI may have made the scenes more visually interesting (to those with shorter attention spans), but sometimes less is more.

While it’s interesting to see the scene with Han Solo talking with Jabba by the Millennium Falcon, in another way, it’s better without that scene, for its omission gave Jabba a sense of mystery (Who is he? What does he look like?) until we finally see his infernal sliminess in Return of the Jedi. Besides, Han’s calling him a “wonderful human being” (my emphasis), even if meant sarcastically, sounds rather out of place (He doesn’t even say that in the novel; instead, he says, “Don’t worry, Jabba, I’ll pay you. But not because you threaten me. I’ll pay you because…it’s my pleasure.”–Lucas, page 89).

There are many variations on how the hero’s journey can be told, depending on the story. Some steps may not be presented in the exact same order, and some may be combined into a single step, or into fewer steps, or omitted altogether. A hero different from the main one may fulfill a few of those steps, too. Depending on one’s interpretation of the plot structure of Star Wars, a number of such changes can be seen to have happened in this film.

The Millennium Falcon’s being pulled by the tractor beam into the Death Star, and the ensuing struggle to rescue Leia and get out, seem to be a combination of the belly of the whale, the road of trials, the meeting of the goddess, approaching the cave, woman as temptress, and the ordeal. Beautiful Leia is thus both the goddess and, in terms of her potential love triangle with Luke and Han, the temptress. Almost being crushed in the trash compactor would be the ordeal.

While many decry the dearth of female characters in the original trilogy, and to mention the only nascent progressivism of 1970s and 1980s movies is seen to be a lame excuse for this dearth; what these three films lack in quantity of strong women is more than made up for in quality of strong women. Iconic Princess Leia is, if anything, a parody of the damsel in distress.

Indeed, Lucas takes the traditional trope of the dashing male heroes rescuing the pretty girl in danger, and he subverts it, not only by showing Leia take charge in the detention area (blasting a hole in the wall leading to the trash compactor), but also by showing how inept Han and Luke are in their bumbling attempt to save her.

As the sparks fly between bickering Han and Leia, we’re already sure of one thing: they have the hots for each other.

One important thing to remember about Luke’s relationship with Ben, though, is that the old man has become the father the boy never had. Luke has transferred his filial feelings from mysterious Anakin onto Ben. With this understanding, we can know what to make of Luke’s watching of the light-sabre duel between Ben and Vader.

When Luke watches in horror at the two men fighting, he sees the symbolic good father versus the bad father. This brings us back to what I said above about psychological splitting. Luke’s rage at seeing Vader cut Ben down with his red light-sabre provokes in him what Melanie Klein called the paranoid-schizoid position, the persecutory anxiety felt as a result of the frustration felt towards the split-off bad parent. Luke fires his blaster at the stormtroopers, wishing he could hit Vader in revenge for having killed the good father…now, for a second time.

On the other hand, Ben’s allowing himself to be struck down is motivated, not only out of a wish to sacrifice himself so the others can escape (thus making his sacrifice to be symbolically a Christ-like one, resulting in Ben changing from a physical to, if you will, a kind of spiritual body); but also as a form of atonement for having failed to train Anakin to be strong enough to resist the temptations of the Dark Side, and for having dismembered him and left him for dead amidst the molten lava of Mustafar. In this sense, it is Ben, rather than Luke, who has made atonement with the father. In his changing into a Force ghost, Ben has also had a kind of apotheosis.

The ultimate boon or reward is achieved when Han and Luke get the Millennium Falcon out of the Death Star and return Leia to the rebels on Yavin. Han will be paid well for his services in rescuing her, but her and Luke’s disapproval of his mercenary attitude will push him to change his ways and receive the ultimate boon: the honour of being a true hero, what Luke has already achieved.

An analysis of the Death Star plans reveals a weakness in its design that the rebels can use to their advantage and destroy it. Here we see dialectics again: “the ultimate power in the universe,” as Motti boasts of the Death Star, “is insignificant next to the power of the Force,” as Vader corrects him.

Han’s refusal of the return, that is, to return to the fight against the Empire, prompts Luke and Chewie to guilt trip him to the point where he, at the last, crucial moment, rescues Luke from without, shooting at the three TIE fighters led by Vader, who is just about to destroy Luke’s X-wing.

Though for the sake of pacing, it was necessary to cut out most of the scenes with Biggs, these omissions were unfortunate; for their inclusion would have added emotional depth to when he is killed. The scene mentioned above, with Biggs on Tatooine telling Luke of his joining the rebels, establishes the two of them as best friends; then the added scene of the reunion of Luke and Biggs among the X-wing fighters, just before they fly off to confront the Death Star, further cements this friendship.

Han’s saving of Luke, though, just before he trusts his feelings and uses the Force to destroy the Death Star, means the boy now has a new friend…and friends are what we need to defeat imperialism.

The Empire Strikes Back

Just as the major planet for the first half of the 1977 film is a barren, hot planet, the major planet for the first half of the 1980 film is a barren, cold planet. Both planets, Tatooine and Hoth, are desolate places in contrast to the city-planet of Coruscant, symbolic of the contradiction between, respectively, the Third and First Worlds; the desert and ice planets are also dialectically opposed for self-explanatory reasons.

Luke’s face being mangled by the Wampa may seem to audiences to be the Star Wars plot’s attempt to explain the change in Mark Hamill‘s looks (he’d been in a car accident in early 1977), but in all likelihood, it wasn’t. Leigh Brackett’s first draft included the Wampa attack, which had the ice creature slash Luke “across the face,” leaving him with “one side of his face a mass of blood”; this was written as early as about 1978, and so thought up even earlier. Hamill wasn’t yet a well-known actor as of 1977, and he looked OK when filmed with Annie Potts in 1978’s Corvette Summer, so neither audiences nor Brackett (in the late 70s, just before she died) would have thought much of the change in his looks by the time of the 1980 film.

The hostility of the Wampas (some of which try to break into the rebel fortress, as seen in some deleted scenes), like the hostility of Tatooine’s Sand People and gangsters, reflects again the alienation felt among the life forms of the desolate, poverty-stricken planets in the Mid and Outer Rims, marginalized by the Empire.

Luke’s only way to save himself from the Wampa is to get to his light-sabre, which is lying in the snow on the ground, out of his reach (for Luke, hanging upside down, has his feet held in ice on the ceiling of the Wampa’s cave). He needs to use the Force, of course.

In Donald F. Glut‘s novelization, Luke imagines the light-sabre already in his hand (Glut, page 192). Just in time, it flies up from the snow and into his hand. This using of the Force involves acknowledging the links between oneself and the objects all around us. Acknowledging such links is part of the cure of alienation, which in turn helps us build the solidarity needed to defeat imperialism.

Speaking of such solidarity, Han is conflicted over leaving the rebels to pay off Jabba the Hutt and staying to help them; his decision to rescue Luke from the icy cold (not to mention his feelings for Leia) resolve his conflict.

The Disney producers of the “sequel trilogy” thought that all they needed to do to pique the interest of Star Wars fans was to have Han, Luke, and Leia involved on some level in the new stories. Those producers missed the point of what made the magic in the three heroes’ presence: their interaction with each other–the bickering, the love rivalry (before Lucas retconned the story to make Leia Luke’s sister, of course), and most importantly, the camaraderie of the three.

Camaraderie among heroic revolutionaries is crucial to defeating imperialism. This is part of the use of the word comrade among socialist revolutionaries. The word gives verbal expression to the solidarity needed as the cure for alienation, and the word also reinforces a sense of egalitarianism.

Contrast this mutual love and respect among the rebels with the mutual ill will and alienation felt among the officers in the imperial army. First, there’s the scowling and sneering between rivalrous Admiral Ozzel and Captain Piett; then there’s Vader’s Force-choking of Ozzel for having been “clumsy” and “stupid” enough to have come “out of light speed too close to the [Hoth] system,” and promoting Piett to admiral.

Luke is not the only one going through the hero’s journey in this movie. Han’s refusal of the call has Leia frowning at him, but their being chased in the Falcon by Vader and the Star Destroyers is his crossing the threshold and road of trials.

Luke’s trip to Dagobah, to be trained by Yoda, is his meeting with the mentor, whose lifting of his X-wing out of the swamp is an example of his supernatural aid. That swamp planet, just like the desert planet and the ice planet, is full of treacherous life forms whose hostility is symbolic of the alienation caused by imperialism. Luke is literally approaching the cave when Yoda tests his ability to control his fear with the Vader apparition.

Han, Leia, and Chewie are symbolically in the belly of the whale when in that giant slug among the asteroids, the chase through which having been a scene in Brackett’s first draft. Han’s growing romance with Leia is his meeting with the goddess, her beauty making her the woman as temptress.

As Luke learns about the Force, we finally learn about the nature of the Dark Side. The spiritually good are “calm, at peace, passive,” while the evil give in to “anger, fear, aggression.” The Dark Side is “quicker, easier, more seductive.” Yoda tells Luke that if you turn to the Dark Side, “forever will it dominate your destiny, consume you it will”…but that’s not entirely true, given that Anakin will redeem himself by the end of Return of the Jedi.

It would be truer to say that, “Once you start down the dark path,” it will be harder and harder to turn back, but not impossible. Yoda’s insistence, on the impossibility of returning to the good side after having gone down the dark path, seems to be an instance of the dogmatism of the Jedi clouding up the truth.

When Luke encounters the Vader apparition in the cave, Luke’s own version of the road of trials, his panicked parrying of Vader’s light-sabre and slicing off of Vader’s head is a wish-fulfillment, Luke’s getting revenge on Vader for cutting through Ben at the neck in their Death Star duel.

Since Vader is the bad father (as discussed above), Luke’s fear in fighting him represents the persecutory anxiety felt in the paranoid-schizoid position. But when the mask explodes and reveals Luke’s face, this represents how the bad father is an internalized object residing in Luke’s psyche. To kill off this introjection is to kill off a part of himself. Thus, Luke must integrate his splitting of good Anakin and bad Vader if he is to find spiritual peace and stay with the good side of the Force. This understanding is part of his atonement with father.

It is interesting to see how Luke, as he learns how to move stones around, is typically in postures reminding us of yoga asanas. In this connection, Yoda’s name (originally Minch in Brackett’s first draft) is an obvious pun on yoga, a philosophy that is all about finding the union, the oneness, in all things, a joining of the human spirit and the Divine spirit.

The energy of the Force “surrounds us and binds us,” as Yoda tells Luke. In the 1977 film, Ben has added that the Force also “penetrates us.” This penetrative aspect within us is the Living Force, existing in the spirit of each living thing, which is rather like Atman; the aspect of the Force that surrounds and binds us is the Cosmic Force, which is rather like Brahman. As an energy field in all things, the Force is thus that infinite ocean I’ve written of so many times–the Unity of Space.

After having tested Luke’s patience by pretending to be just an annoying little alien (a test Luke fails when he presumes that the “great warrior” could never be this “little fella,” an implied racial prejudice Luke quickly outgrows), Yoda scoffs at Luke’s longing for adventure, his having always “looked away to the future, to the horizon…never his mind on where he was, what he was doing.” If Luke wants to master the Force, he must focus on the Eternal NOW–or as I’ve called it, the Unity of Time–rather than the past or the future, which are just human constructs and have no basis in material reality.

Very little in these movies is overt about the capitalist basis of imperialism, but there are a few significant indications. Jabba the Hutt is a gangster, and as I’ve shown in a number of film analyses, mafias–criminal businesses–make a perfect metaphor for capitalism. Han owes Jabba for having dumped off spice, a narcotic many in the galaxy use recreationally as a manic defence against the despair they feel from their alienation. The Empire may disapprove of the trafficking of spice, but it sometimes has uses for gangsters and bounty hunters, too.

Later, when Boba Fett finds Han Solo, Darth Vader is content to let the bounty hunter take Han to Jabba the Hutt once Vader has Skywalker. Fett is worried that, if Han dies either through the torturing (to make Luke want to come to Bespin) or through the carbon freezing, Han’s great worth will be reduced to nothing. In other words, Han is being treated as no more than a commodity, a common problem those in the sex industry suffer under capitalism.

To get back to Luke, though, his training in the Force is moving him further away from alienation and closer to a linking with all things. As he moves stones around, Yoda’s soothing voice tells him to “feel” the Force, that is, the connections between all things that make moving things with one’s mind possible. When Luke can’t imagine how he can lift his X-wing out of the water with his mind, he is ignoring the microscopic wave-particles that are everything, and he’s ignoring how the Force links all things together.

On Bespin, a planet whose theme, oddly, is clouds and sky rather than land or water, Lando Calrissian has set up a business independent of imperial meddling. His business would seem to represent the right-wing libertarian ideal of capitalism without government interference. Up in the sky, among the clouds, Bespin is a heavenly utopia…

Let’s remember, though, that Lando isn’t exactly trustworthy. He’s been a “gambler, con artist, all-around scoundrel,” as Han describes him in the novelization (Glut, page 275); so we should be wary of Lando’s conception of utopia. He has won the ownership of a Tibanna gas mine in a sabacc match, or so he claims. He’s not part of the mining guild, which on the one hand would be a cartel regulated by the Empire, but on the other hand would be, in part, like a trade union. Free-market-minded Lando, with his lack of love for the Empire, would never want inclusion of his business in a guild.

In fact, in his desperate–and ultimately futile–attempt to protect his business from the Empire, Lando makes a deal with Vader to hand over Han, Leia, and Chewbacca. The fascist capitalist state that is the Empire, however, betrays Lando with the “altering [of] the deal” as cold-bloodedly as he has betrayed Han et al, in true Judas Iscariot fashion. Right-wing libertarians similarly pose as anti-government, yet they’ll support the state if it’s convenient for them. Just take note of the Koch brothers to see what I mean.

Right-wing libertarians fail to see the link between capitalism and the state, in part, because they imagine the old free-competition of the 19th century to be something they can revive as long as they minimize ‘pesky, intrusive’ government. But capitalism in its modern, imperialist stage is a concentrated, centralized, monopolistic form in which industrial cartels have been merged with the banks, resulting in finance capital. The need for markets to expand ever-outwards and take over foreign lands, as a counterweight to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, renders a return to the “free market” an impossibility. Capitalism without a state that’s protective of private property is also an impossibility.

The Empire’s takeover of Lando’s mining business is teaching him the reality of these impossibilities, and teaching him the hard way, so he quickly repents of his betrayal of Han, Leia, and Chewie. As a member of the vacillating middle bourgeoisie, Lando may be what Mao considered an enemy of the people if he shifts to the right, or he may be considered the proletariat’s friend if he shifts to the left. The Empire has pushed him to the right by making him betray our rebel heroes, but the imperial takeover of his business has pushed him to the left, so now he wants to help Han, Leia, and Chewie.

The suffering that Han, Leia, and Chewie are forced to endure is that part of the hero’s journey known as the ordeal. The freezing of Han in carbonite is, once again, the belly of the whale, with him as Jonah, who formerly didn’t want to do God’s work and preach to the people of Nineveh, and when freed from the “great fish,” Jonah had changed and would do the right thing. Han hasn’t committed himself to the cause of the rebellion, but being encased in carbonite will effect a spiritual transformation similar to Jonah’s.

Frozen Han, taken to be put aboard Slave I, looks like he’s the focus of a funeral procession. It’s as if he is dead, taken in a coffin. In James Kahn‘s novelization of Return of the Jedi, Han speaks of his experience of having been frozen in carbonite: “That carbon freeze was the closest thing to dead there is. And it wasn’t just sleepin’, it was a big, wide awake Nothin’.” (Kahn, page 370)

When he’s unfrozen in Return of the Jedi, his will be a Christ-like resurrection, Han’s apotheosis. Lando, as the Judas of this Passion, doesn’t even get his thirty pieces of silver from the Empire; instead, he has his business taken from him. He doesn’t hang himself in remorse: Chewbacca chokes him instead.

Meanwhile, Luke has had visions of a future in which his friends “are made to suffer.” (I wonder if Yoda has put the visions in Luke’s head, to test him again.) Nonetheless, Luke on Dagobah should be keeping his focus on the NOW, rather than be distracted by the future, which is “always in motion.” His fears of the future are a temptation to the Dark Side.

When Luke rushes over to Bespin to face Vader, it’s yet another example of the rebels fighting against formidable odds. One must fight the Empire, but Luke isn’t ready. He hasn’t learned how to control the Force. Though he’s controlling his fear and anger, he has revenge in his heart.

With the understanding that Vader is the bad father, Luke’s light-sabre duel with him is a dramatization of Luke’s experience of the paranoid-schizoid position. Vader–as the bad father using the Force to hurl objects at Luke, hitting him with them–is thus the ultimate abusive parent.

His causing Luke to lose his grip on his light-sabre, as well as cutting off the hand that holds it, makes Vader a symbolically castrating father as well. His revelation that he is Luke’s father, saying, “Search your feelings; you know it to be true,” means Luke can already feel, through the Force, that Vader really is his father. Only splitting and projection can cause Luke to feel any doubt that Vader and Anakin are the same man.

The wish to keep the good and bad fathers split means Luke cannot bear that Vader is telling him the truth, so he’d rather fall to his death. Hanging outside, below Cloud City, Luke is experiencing a kind of dark night of the soul, an existential crisis. Becoming a Jedi was supposed to be about Luke identifying with his father; such an identification gave his life meaning. But if his father is the very evil he has been trying to defeat, then what meaning can there be in his life?

Now, in order to achieve this identification, Luke has no choice but to experience reparation with the father, in his good and bad aspects as they exist in Luke’s psyche, a true atonement with the father. This is what Melanie Klein called the depressive position: Luke must also cope with the Dark Side of the Force to grow spiritually.

As I said above in the discussion of Luke’s father and the Force, these two are interconnected. A reconciliation of Anakin with Vader is intimately related with ‘bringing balance to the Force,’ or sublating the good and dark sides of it. Since, as I said above, the Force can be seen to represent the dialectic, which involves a resolving of such contradictions as the light and dark sides of the Force, a reconciling of Anakin and Vader, the good and bad father, is another such dialectical sublation.

In the fight against imperialism, we all–as a part of our own hero’s journey–must resolve dialectical contradictions such as those of the rich vs. the poor, the oppressors vs. the oppressed, the state vs. the people, etc.; but also we must make reparation, as best we can, with all those people in our lives whom we split into good and bad versions, then project their bad parts out, far away from ourselves, in an attempt never to have to deal with our shadows.

Luke must learn how to achieve such a reparation. When he has resolved and reunited the good and bad objects in his mind, he’ll be a true Jedi Knight. This ability to accept the Anakin in Vader, and the Vader in Anakin, is how he can have already learned all that he needs to learn, with no more need for training from Yoda by the time of the beginning of Return of the Jedi.

Return of the Jedi

Just as in Star Wars, the emphasis is on the good side of the Force and on Luke’s father as a good, but mysterious, man (we didn’t know Vader is Anakin, for the ret-con hadn’t happened yet); and in The Empire Strikes Back, the emphasis is on the Dark Side of the Force (Vader’s Force-choking of Ozzel and Needa to death, Luke’s failure in the cave, and the cliff-hanger ending) and Vader as Luke’s bad father revealed; in Return of the Jedi, we have a sublation of the light side thesis and dark side antithesis, and of Vader as having equal potential for evil and good.

And just as, in the original version of this trilogy, Jabba the Hutt was something of a mystery until the 1983 film, so was the Emperor largely only spoken of until this third film. (Though the switch from Clive Revill‘s Emperor to that of Ian McDiarmid in the later version of Empire Strikes Back was one of the few justified changes that Lucas made–for the sake of preserving continuity among all six films–I’ll always have a nostalgic place in my heart for the Revill performance.) The paralleled late emergence of these two villains suggests, in personified form, the dual mysterious cause of all our oppression (capitalism and its state) being discovered only at the end, after careful reflection frees us from our cultural brainwashing.

As I said above, gangsters like Jabba the Hutt represent the capitalistic aspect of oppression in the galaxy, and the Empire represents the statist aspect. Just because the Empire apprehends smugglers of spice (Jabba’s drug business), though, this doesn’t mean the capitalist and statist aspects are mutually exclusive, as the right-wing libertarians would have us believe.

Vader allowed Boba Fett to take Han Solo to Jabba rather than follow the bounty hunter to Tatooine and do a sting on the gangster in his palace, thus to eliminate a huge part of the spice trade once and for all and morally justify the Empire’s authoritarian rule. This inconsistency of the Empire to arrest some smugglers, but not go after their bosses, is in a sense comparable to the US government’s hypocritical “War On Drugs,” which was an excuse to target counter-culture types like the hippies and the Black Panthers (of whom the Star Wars equivalent would be miscreants like Han Solo), but also, through the CIA, subjected many non-consenting Americans to LSD.

Another similarity between what Palpatine and Jabba represent is the commodification of living beings. The Emperor wants Luke to replace Vader as his Sith apprentice; he would own Luke. As he says to Luke in that sublimely evil voice, “You, like your father, are now…mine.”

That Jabba commodifies others is so obvious that it scarcely needs going over, but I’ll do it anyway. Apart from keeping Han frozen in carbonite and hanging him on a wall like a work of art, a human being treated as a mere possession, Jabba has females chained up near him to dance for his pleasure…and if they don’t want to satisfy his lust (which, naturally, is invariably not wanting to), they can sate the Rancor‘s appetite instead.

When Han is released from the carbonite, not only is this a symbolic resurrection (and his time in Jabba’s infernal palace, with all of its horrors, is like a harrowing of hell), but it’s also rather like Saul’s conversion to Christianity, since Saul was blinded temporarily when encountering Christ on the road to Damascus. Now, instead of refusing the call to adventure (as Saul refused to be a Christian), Han, upon his rescue from Jabba, can commit to helping the rebellion (as Saul, renamed Paul, could commit to spreading the word of the gospel).

The contrast between alienation and solidarity is striking: Jabba and his fellow scum laugh at the suffering and death of others (even the Gamorrean Guard gets neither pity nor help when he falls into the Rancor’s pit); while Leia, Chewie, Lando, and Luke all work together to save Han, Luke even saying that Jabba may profit from a deal from releasing Han.

When Jabba dies, it’s ironic how Leia uses the very instrument of her enslavement and commodification by him–the chain–to strangle him to death with. His fat, slimy ugliness is a perfect image with which to present his licking lechery, for it is this very goatish, gluttonous expression of lust that makes such men so unattractive to the beautiful women they desire. It’s also fitting that his little pet is named Salacious Crumb.

The commodifying of Luke, Han, et al is carried further when they’re all punished for Luke’s killing of the Rancor (the only living being any of Jabba’s scum feel pity for). The Sarlacc is a giant mouth in the Dune Sea, in the middle of the Tatooine desert (a monster preferably without the added CGI); the throwing of victims into it, treating them as mere food, is the ultimate commodification of the living.

After rescuing Han, Luke returns to Dagoba, only to find Yoda dying of old age after having confirmed that Vader is Luke’s father. Now Luke, for sure, must reconcile the good father with the bad, an experiencing of the depressive position, a resolving of opposites, the dialectical sublation of the good and bad sides of the Force that will ensure that he is a true Jedi Knight.

Indeed, Luke’s wearing of black, and even having worn a black cloak when entering Jabba’s palace, make him look like a Sith Lord, though he is in no way surrendering to the Dark Side. The contrast of his clothing with his light-side leanings symbolically suggest such a sublation of the good and bad.

Still, resolving those dark and light contradictions doesn’t mean he won’t have to face Vader again. When opposites are sublated, the cycle of the dialectic begins again: the sublation becomes a new thesis to be negated, and these two contradictions must be sublated. Luke, with the integration of the internal objects of the good and bad father, must face evil and be tempted by it (his wearing of black in part symbolizes that temptation), as it’s personified in Vader and the Emperor.

Because of the integration of the good and bad father that Luke has experienced, he tells Ben’s Force ghost that there is still good in Vader, to which Ben replies that there’s “more machine than man” in Vader. Not only is this true in the sense that Vader is a cyborg (mechanical arms, legs, and breathing apparatus), but also in the sense that he is a slave to the imperial machine. With Luke’s love for Anakin, we begin to feel something we hitherto never thought we would: we pity Vader.

This ability to feel pity and love (as opposed to the heartless cruelty just seen among Jabba and his ilk), a pity extended even to a villain who is actually enslaved to the Emperor, is a crucial ingredient in the defeat of imperialism. Recall what Che once said about love: “the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.”

Ben imagines Luke’s pity and love to be excessive, as something ruining their hopes of defeating the Empire. Then Luke says that Yoda spoke of another hope…

…and as soon as I hear Ben say that the other Skywalker is Luke’s twin sister, I think of how moviegoers must have first reacted to this in theatres back in 1983. They must have been cringing and squirming in their seats, whispering to themselves, “Please, Lucas! Don’t make her Leia! Don’t make her Leia!” And then, when Luke says, “Leia! Leia is my sister!” those moviegoers must have reacted as Vader did when learning he killed Padmé: “NOOOOOOOO!”

…and somehow, Leia has always known Luke was her brother, which means she must have known when she gave Luke those kisses that got him so excited. And why didn’t Luke feel even private embarrassment at all that previous sexual innuendo with his “sister”? I can accept the ret-con of Anakin as Vader, but the incestuous implications of this new change make it more difficult to smooth over (especially since Leigh Brackett’s first draft had Luke’s sister as someone else, someone named Nellith). Yes, even the sacred original trilogy has its flaws.

Our heroes go to the moon of Endor to knock out the new Death Star’s deflector shield. The theme of this moon is all forest, suggestive of the jungles of Vietnam: I make this comparison because Lucas, in a discussion of Star Wars with James Cameron, stated explicitly that the Ewoks, with their primitive weapons going up against the Empire and its vastly superior technology, were meant to represent the Viet Cong and their resistance to US imperialism. The rebels are also “Charlie.”

As you can see, Dear Reader, I’m not merely imposing a Marxist agenda on Star Wars. There is real evidence to back up my interpretations. Lucas, having begun filmmaking during the antiestablishment 1970s, was a left-leaning liberal back in the days when that modification, “left-leaning,” actually meant something, even if used among bourgeois Hollywood liberals whose political ideals are far removed from mine.

Though Lucas’s egregious fourth Indiana Jones movie fashionably vilified the Soviet Union, to be fair to him, he also acknowledged, in an interview, the greater artistic freedoms given to Soviet filmmakers, if not the freedom to criticize the government. The capitalist compulsion to maximize profits has always stifled artistic freedom.

Though the Ewoks represent the North Vietnamese, their physical form, as space-age teddy bears, was another fault of the film. “Dare to be cute,” Lucas said. Speaking of capitalism, the Ewoks–whose name we knew even though ‘Ewok’ is never said in the movie–were a toy to be sold and profited from, to say nothing of the Ewok movies and cartoons. At the risk of contradicting myself with my above preaching of pity, I must acknowledge that we Ewok-haters can comfort ourselves when we, at least, get to see a few of them die during the Battle of Endor.

To elaborate again on the hero’s journey, as it is manifested in Return of the Jedi, Yoda and Ben telling Luke he must face Vader again is his call to adventure. We see Luke’s refusal of the call when he says he can’t bring himself to kill his own father. Luke’s interacting with Yoda and Ben’s Force ghost is his meeting with the mentor and supernatural aid. Luke’s giving himself up to the Empire on Endor is his crossing the threshold and the beginning of his road of trials. His going with Vader to the new Death Star is his approaching the cave. Inside the Death Star with Vader and Palpatine is Luke in the belly of the whale, and his agony at watching the rebel fleet attacked by the imperial fleet is his ordeal.

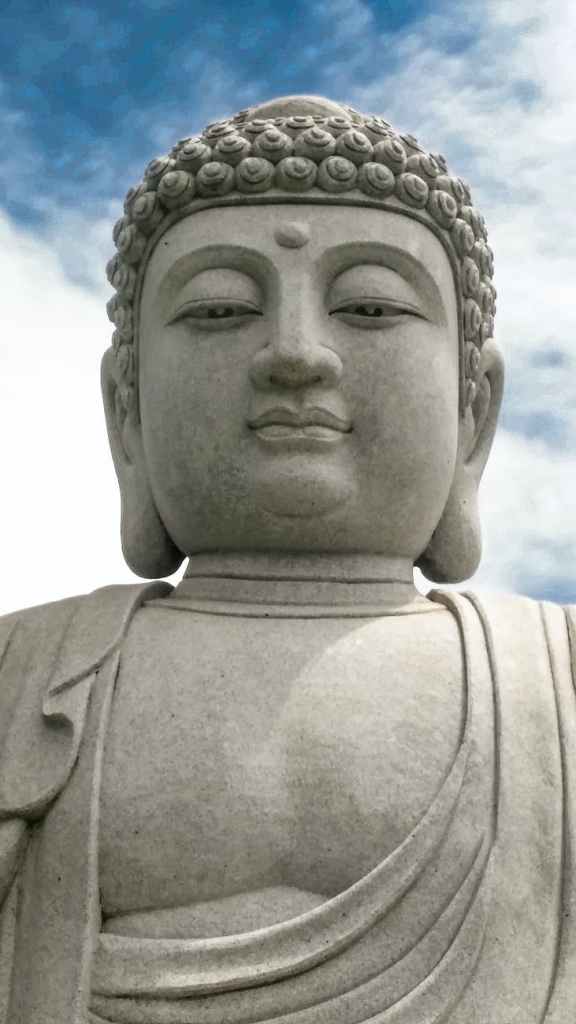

Luke’s temptation, to take his light-sabre and strike the devilish Emperor down with all of his hatred, is like Jesus’ temptation by Satan in the wilderness, and like the Buddha’s temptation by Mara while sitting under the Bodhi tree. After Luke’s successful resistance to the temptation, it is understood that he will train a new order of Jedi Knights, just as Jesus gathered his twelve disciples, and the Buddha began his teaching of the Dharma, after their triumphs over temptation.

Luke’s light-sabre, lying on the arm of Palpatine’s throne rather than in Luke’s hand, is representative of Lacan‘s notions of symbolic castration and lack, which lead to desire. Desire here is not to be understood in the sexual sense, but lack as the cause of desire (i.e., want in both senses) is clearly relatable to Luke’s temptation; and Palpatine is exploiting this want to the hilt. Indeed, the Emperor’s feeling of Luke’s anger, the hate that is swelling in him, is giving Palpatine a high comparable to that of cocaine.

“Man’s desire is the desire of the other,” Lacan said, meaning that we desire the recognition of others, and we desire to be what other people desire. Luke wants his father to acknowledge him as a Jedi, and he wants Anakin to want to be a Jedi again. Vader wants what Luke wants, only we must replace the word Jedi with Sith. Palpatine wants mutual alienation among all three of them.

Between the inability of Han’s team to knock out the Death Star’s shield generator, the rebel fleet having to face not only the imperial fleet, but also a fully-armed and operational Death Star, and Luke’s growing temptation to give in to his anger and hate, we see again how the anti-imperialists face near-impossible odds.

How can they overcome such a formidable foe? Through linking, connecting, and solidarity, which come from empathy and love. Up until this film, we’ve seen largely human rebels, without any alien comrades (save Chewie). Now, not only have the rebels linked with the Mon Calamari (led by Admiral Ackbar) and Lando’s first mate aboard the Falcon, Nien Nunb, they have also linked with the Ewoks, who will be a crucial distraction for the imperial troops on Endor.

During Luke’s duel with Vader, once he’s regained control of his anger, he must be sensing through the Force that the tide is turning with the space battle and the struggle on Endor, and that the shield generator is finally down. Luke works on building his link with Vader by mentioning the good he feels in his father, the conflict between Anakin and Vader.

Later, Luke’s fear for his friends, especially for “Sister,” is an echo of young Anakin’s fear for his mother and for Padmé; so Vader can exploit Luke’s fear to bring him out of hiding. Vader pushes Luke too far, though, by suggesting finding Leia and turning her to the Dark Side, and Luke’s need to protect one link paradoxically endangers his link with his father.

Slicing off Vader’s mechanical hand holding his red light-sabre, a symbolic castration comparable to usurping Cronus emasculating his father Uranus, Luke is now in the position to usurp his father as Palpatine’s new apprentice. Luke looks at his own mechanical hand, remembers how much of Vader’s body is machine, and regains his compassion for the Anakin inside.

Foolishly, though, Luke throws his light-sabre away, a symbolic castration of himself, for he now has no protection from Palpatine’s Force lightning. Though love and compassion are crucial, necessary conditions for defeating imperialism (in how they help form links between people to build solidarity and eliminate alienation), they are not sufficient conditions. There are still contradictions to be resolved, and we resolve them by fighting the Empire.

We see rebels in uniforms, just as we saw the Soviets in uniforms during the Cold War, because they all knew the realities of imperialism: they had an enemy to fight, and wars are won only through military discipline, as personified in troops in uniforms. Luke must keep his compassion, but he mustn’t act like a soft-hearted liberal.

Now that Luke is being zapped with the Emperor’s Force lightning, there’s only one hope of him being saved–by the Anakin buried deep down inside of Vader. This stage of the hero’s journey is rescue from without, just as–at the end of the first Star Wars movie–Luke needed Han to intervene when Vader was about to blow him up in his X-wing as it flew along the Death Star trench.

In this tense moment, with Vader looking back and forth between Luke and Palpatine, we feel as though we can see through his mask to see the conflict on his face. We don’t need the scene altered, with Vader saying “No” before picking up the Emperor and throwing him over the precipice. This sacrificial act, Anakin’s redemption bringing balance to the Force, is the atonement with the father.

After blasting the Death Star’s reactor, Lando must fly the Falcon outside in time before the whole space station blows up, as must Luke while carrying Vader’s dying body. This final struggle is, at least in a symbolic sense, the crossing of the return threshold, the road back.

Back in The Empire Strikes Back, when we saw the back of Vader’s scarred head without his helmet on, it looked creepy, because we thought of him merely as a villain. Now that we’ve made a link with Vader through Luke’s love, we see his scarred head and face with ironic pity. Instead of cheering for Vader’s death, as we would have had it happened in the 1977 film or three quarters into the 1980 film, we’re saddened.

Back on Endor with the victory celebration, we see the apotheosis of the Force ghosts of Anakin, Yoda, and Ben, the masters of the two worlds of the Living and Cosmic Force. Redeemed Anakin (best seen played by Sebastian Shaw!) has experienced, if you will, a kind of resurrection. The linking of all life forms in the galaxy, the end of their alienation, replaced by love, empathy, friendship, and solidarity, is the ultimate boon and reward, giving them the freedom to live without imperialism.

The Phantom Menace

Since the prequels are so obviously inferior to the original trilogy, I won’t be going over them in quite as much detail. Nonetheless, in terms of exploring political allegory, there are some interesting ideas in these films.

Many people have criticized Episode One for having so bland an opening conflict as the taxation of trade routes to outlying star systems. Actually, the film itself acknowledges this blandness when Qui Gon says, “I sense an unusual amount of fear for something as trivial as this trade dispute.” To me, it seems reasonable to start the conflict with something small and build from there.

Let’s reconsider this trade dispute as an allegory for the beginnings of neoliberal capitalism in the mid-1970s. While it’s easy to see the Empire as symbolic of the fascistic extreme of statism, we should see the Trade Federation, with its droid army, as symbolic of the more capitalistic aspects of imperialist aggression. Recall that the East India Company had its own army.

The greedy Trade Federation is opposed to the taxation of trade routes, just as “free market” capitalists are opposed to higher taxes. The Trade Federation blockades and invades Naboo, causing a “death toll [that] is catastrophic,” symbolic of how “free market” capitalists insinuated their way into the Western political system, resulting in Reagan, Thatcher, etc., and beginning the widening of the gap between the rich and poor, in turn resulting in more homelessness and other forms of suffering. This suffering has crept in…insidiously…

Controlled opposition between the Republic and the Trade Federation has been orchestrated by the Sith, symbolic of the ruling class that pits liberals against right-wing libertarians. Palpatine’s plan is divide and conquer.

Market fundamentalists like to fantasize that there is no coercion in “true capitalism.” Reagan and Thatcher, who preached about “small government,” nevertheless bloated the state with the arms race and engaged in such coercions as the Falkland Islands War and the invasion of Grenada. Capitalism, in the form of imperialism, forces itself on people far more than Reagan’s so-called “evil empire,” the USSR, did.

Alas, what could have been done to fix the many things that were wrong with the prequels? I’d say, essentially, that Lucas should have done what he did with Empire and Jedi: he should have collaborated on the script (i.e., written out basic treatments, and used his money to pay first-rate screenwriters to do rewrites of his clunky dialogue), hired talented directors to inspire better performances, and he would thus have been free to focus on what he’s good at–world-building and visuals (i.e., production).

As for the interesting theory by Lumpawaroo on Reddit–that Jar Jar Binks was really a secret master of the Dark Side, whose clumsiness was really a kind of zui quan (pronounced “dzway chüen”); and he would have shown his true colours in Attack of the Clones, had Lucas not chickened out after the backlash from fans–I imagine such a change would have improved Phantom Menace, at best, only marginally, since, as we know, so much more was wrong with the movie.

Presenting Anakin as a yippee!-shouting little kid deflates his grandeur as a tragic hero, Macbeth-style, in the worst way. Still, I feel sorry for Jake Lloyd and Ahmed Best, who’d had such high hopes that Phantom would shoot their acting careers into the stratosphere, instead of making them objects of ridicule and fan hate.

We learn that Anakin’s was a virgin birth. Qui Gon believes that the boy is the fulfillment of a prophecy that someone, especially endowed with the Force, will bring balance to it. In other words, Anakin is to be understood as a Christ-like, Messiah figure. Given what we know Anakin will eventually become, we wonder if he’s really Christ, or Antichrist.

This extreme good, at one with extreme evil, leads us back to dialectics. Qui Gon believes Anakin was conceived by the midi-chlorians; while, in Revenge of the Sith, Palpatine, when speaking of Darth Plagueis‘ ability to influence the midi-chlorians to create life, will imply that he (or Plagueis?) used them to create Anakin. Did ‘God’ create Anakin, or did ‘the Devil’? Was his creation a bit of both good and bad fathers?

…and now we must come to a discussion of a much-hated topic among Star Wars fans: midi-chlorians. Fans complain that midi-chlorians, in giving a quasi-scientific veneer to the Force, cheapen and demystify it, taking away its mysticism. I’m pretty neutral in my attitude towards midi-chlorians: I can take them or leave them.

Since we already know why most people dislike the idea of midi-chlorians, to balance things out, let’s consider a brief defence of them. First of all, they are not the Force; they are merely microorganisms that connect living beings with the Force. We all know that some are more Force-sensitive than others, and that the greater or lesser number of midi-chlorians simply explains these differences. The Force itself remains a mystical enigma.

Secondly, the Jedi’s understanding of midi-chlorians could be seen as a misunderstanding. Never assume that Lucas’s characters, including the sympathetic ones, always reflect his own personal philosophy of the Force. One of the things we glean from the prequels is how neither the Jedi nor the Republic are infallible: their collective errancy, both in knowledge and in morals, is a major factor in their downfall and in the rise of the Empire. The Jedi’s theory behind midi-chlorians, at least in part, can be seen as every bit as much a pseudoscience as creationism is for Christian fundamentalists. The greater or lesser midi-chlorian count can be the pseudoscientific basis of feudal Jedi elitism.

Thirdly, the midi-chlorians seem to be an introduction to Lucas’s concept of the microscopic Whills. He insists that he had this idea way back in the mid-1970s, though he hadn’t yet gone public with it. The Journal of the Whills was introduced in his novelization (page 4); we don’t know for sure if he’d meant at the time that the Whills were micro-biotic (and given all of his ret-cons over the years, we might imagine that, for all we know, the Whills were originally giants!), but it’s far from impossible that they were always meant to be microscopic. A pun on mitochondria, the midi-chlorians aren’t the Force, but they connect a Jedi with the Whills, which are the Force…and as I’ve argued repeatedly here, links and connections between living things are what this saga’s moral base is all about.

Finally, the microscopic Whills could be seen to symbolize the particle/wave duality in everything, the “energy field created by all living things.” The point is that mysticism hasn’t been replaced by “junk science,” but rather that it has been complemented with something part-junk, part-real science. Science and religion aren’t necessarily always in a state of mutual contradiction.

Back to the story. Anakin is a slave, indicating how the Republic, failing to solve this violation of a living being’s rights, is far from the ideal form of government we assumed it was from the original trilogy. The bizarre election of queens, who serve mere terms in power, rather than rule in the context of hereditary dynasties, allegorically suggests the phasing out of feudalism and phasing in of capitalism.

The only way one could conceivably rationalize the nonsensical form in which politics are depicted in Star Wars is to say that, “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away,” people arranged power structures far differently from the way we have arranged them here on Earth. Class struggle, in the forms of master vs. slave, feudal lord vs. peasant, and bourgeois vs. proletarian, is shown with these forms coexisting simultaneously rather than replacing each other in succession, as if to make a commentary on the commonality of all three power structures on our planet. Willing suspension of disbelief, my dear readers…

Anakin’s being taken away from his mother, Shmi, has been traumatizing for him, as it would be for any of the younglings separated from their parents at so tender an age. The difference, however, between Anakin’s yielding to the Dark Side, versus the other younglings’ staying with the light side is Anakin’s bad influence, Palpatine, as will be dealt with below.

The Jedi replacement for empathic parental love is mere submission to authority, which under normal circumstances can be kept stable, despite how problematic it is; but the danger of the narcissistic lust for power that the Sith represent shows the cracks in not only the Jedi armour, but also that of the bourgeois democracy of the Republic.

The Jedi Council sense Anakin’s fear and knows the danger such fear leads to, but they have no empathy for a boy torn away from his mother; they, after all, have been torn away from their parents at so much younger an age that they’ve lost touch with such feelings of familial attachment. Their own failed linkages to the most crucial ones of their early lives has clouded their judgement on so many other matters.

Many have criticized the ‘boring’ political scenes in the prequels, but a presentation of politics is indispensable to their plot. Here we see how Palpatine has manipulated his way into power. Why would we not see the politics behind his rise?

We see not only how he puts on a superficial charm, with his avuncular smiles, but also the corruption in the Republic, kowtowing to the Trade Federation and their bribery. The relationship between the Republic and the Trade Federation parallels the true relationship between the state and capitalism, however the right-wing libertarians may try to deny it.