I: Introduction and Cover

Brain Salad Surgery is ELP‘s fourth studio album, released in late 1973, after the prog rock supergroup‘s eponymous debut, Tarkus, the live album Pictures at an Exhibition, and Trilogy. It was produced by singer/bassist/guitarist Greg Lake, as were all of the trio’s previous albums.

Though it initially got a mixed critical response, Brain Salad Surgery‘s reputation has improved over time. It had always been a commercial success, reaching #2 in the UK and #11 in the US; it eventually went gold in both countries.

Here is a link to the full album, and here‘s a link to all of the lyrics.

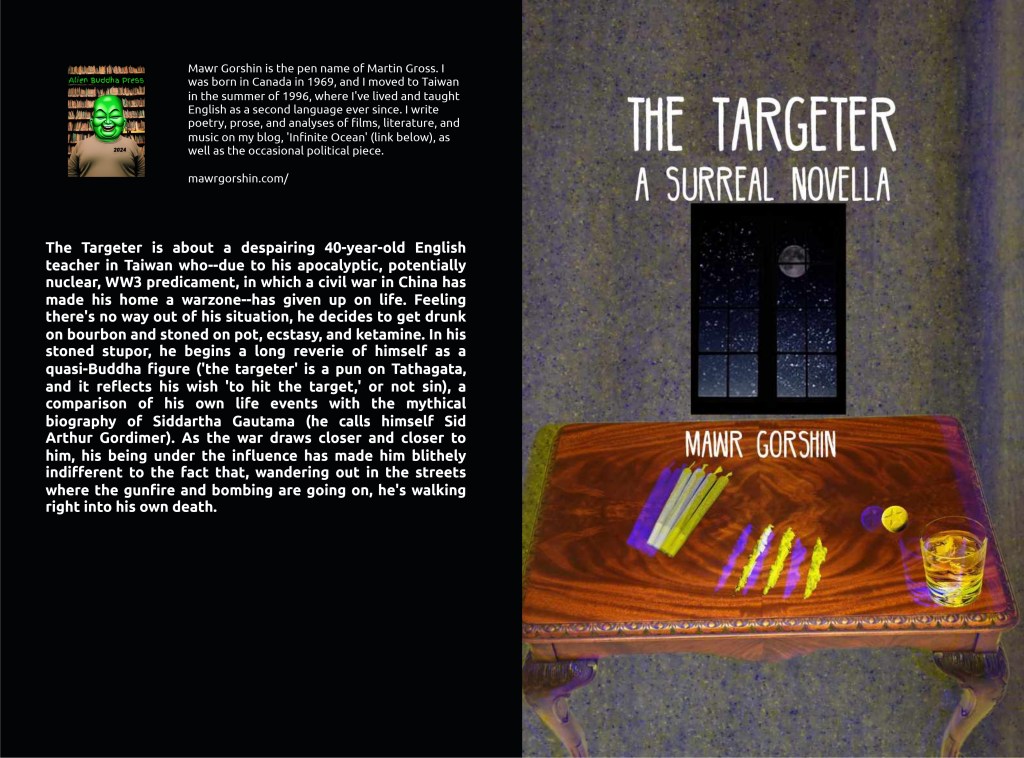

HR Giger‘s superb album cover gives a vivid visual representation of the album’s central theme of duality–male vs female, man vs machine, and good vs evil. The male/female duality is represented by the woman’s face in the circle in the middle of the cover; under her chin is the end of a phallus pointing up along her neck, the rest of the phallus being represented, outside the metal circle, by a short cylinder and a circle with ELP representing the balls. The record company insisted on removing the phallus for obvious reasons, so on early releases of the album, one instead saw it airbrushed away and replaced with a…shaft…of glowing light.

The album’s title–derived from the lyrics to Dr. John‘s “Right Place, Wrong Time” (released earlier the same year), and replacing ELP’s working title, Whip Some Skull on Ya–is a reference to fellatio, hence the phallus just under the woman’s face…and the skull at the top.

The cover originally opened up, like two front doors to a building, to reveal the whole head of the woman with her eyes closed, as opposed to seeing the skull’s eyeholes over her when the cover is closed, indicating the dualities of life and death, good and evil, and man and machine.

II: Jerusalem

Side One begins with two tracks that are adaptations of other composers’ works, something the band had done several times before, as with pieces like “The Barbarian” (based on Bartók‘s Allegro barbaro for solo piano), “Hoedown,” by Aaron Copland, and the aforementioned piano suite by Mussorgsky. As for track one of Brain Salad Surgery, ELP did an arrangement of a hymn by Hubert Parry, who set William Blake‘s poem, “And did those feet in ancient time” (from the epic, Milton), to music.

“Jerusalem” was released as a single, but it failed to chart in the UK; actually, the BBC banned this ‘rock’ version for potential “blasphemy” (despite how reverent the band’s arrangement was). Apart from being understood as a religious song, “Jerusalem” is also considered patriotic to England, even proposed as the national anthem.

Now, the long-held modern assumption that Blake’s text is based on an apocryphal story–about Jesus walking on English soil during His lost years–is unlikely to be true, because no such story existed, apparently, before the twentieth century; instead, Blake’s text is based on a story that it was Joseph of Arimathea who allegedly went to England to preach the Gospel there. I find such an interpretation hard to follow, though, since the text explicitly refers to “the holy Lamb of God” and “the Countenance Divine” being in England.

In any case, the notion that the feet of Christ (or those of Joseph of Arimathea, for that matter…whichever) sanctified English soil by treading on it is jingoistic nonsense that actually turns the meaning of Blake’s poem into its opposite. The key to understanding the text is not “England’s green and pleasant land,” but rather “these dark Satanic mills,” referring to the early Industrial Revolution and its destruction of nature and human relationships, or to the Church of England and how it imposed conformity to the social and class systems.

People who see patriotism and conventional Christianity in Blake’s poem are blind to his irony in using Protestant mystical allegory to express his passionate advocacy for radical social and political change. He wasn’t saying that Jesus walked in England, thus making it ‘the greatest country in the world,’ and worthy of global domination. He was asking if Jesus went there, where the “dark Satanic mills” would later be found.

That he meant such a visit seems unlikely, but if the visitor was Joseph of Arimathea, at least he would have done a proselytizing of the primitive Christianity of the first century AD, not that of later centuries, with the corrupt Catholic or Protestant Churches of Blake’s time, those that subjugated other lands and justified their imperialism with their ‘superior, civilized’ religion.

Blake says he “will not cease from Mental Fight” (my emphasis), meaning his moral struggle with the powers-that-be, the industrial capitalists who used religion as Marx would later call “the opium of the people” to maintain social control in the interests of the ruling class. Blake’s bow, arrows, spear, and sword are metaphors for all he would use to bring about revolution and social justice (his metaphor for these being “Jerusalem”) in England; they were never meant to aid in the building of empire, much to the chagrin of the British patriots who want to read his poem in that way. Even Parry grew disgusted with the jingoistic misuse of his hymn.

This ironic surface patriotism and conformist piety as cloaking Blake’s real revolutionary social critique plays well into the theme of duality–good vs evil–on Brain Salad Surgery. Similarly, it’s fitting that keyboardist/composer/arranger Keith Emerson should have done an adaptation of Parry’s musical setting, one with the usual Emersonian pomp embellishments, but still reverent to the piety of Parry’s music. For again, such a musical style, soon to be contrasted sharply with that of the next track on the album, is a part of the good-vs-evil dualism of Brain Salad Surgery.

III: Toccata

The “dark Satanic mills” of the first track seem to be vividly depicted, in musical form, in this next ELP adaptation of a composer’s work, this one being the fourth movement of the first piano concerto of Argentinian modernist composer Alberto Ginastera. The movement is titled toccata concertata, hence the name of ELP’s adaptation.

Unlike the trite harmony of Parry’s work, this one is violently dissonant, something accentuated by Emerson’s use of raspy synthesizer sounds. Indeed, the dissonance of this adaptation makes King Crimson sound like the Bay City Rollers in comparison.

Another valid comparison of ELP with King Crimson, as far as this second track is concerned, is how we hear a push towards the most state-of-the-art technology. Recall how the 1980s King Crimson used guitar synthesizers, the Chapman stick, and Simmons electronic drums. “Toccata” boasts (as does “Jerusalem”) the use of the very first polyphonic synthesizer, the Moog Apollo, and eight specially developed drum synthesizers, used in the track’s middle percussion section, arranged by drummer/percussionist Carl Palmer.

Again, this use of the latest technology of the time, as mixed in with more conventional instruments and singing, reflects the album’s theme of dualism–in this case, the dualism of man vs machine.

I’d like to do a comparison/contrast of Ginastera’s fourth movement with ELP’s adaptation. I won’t cover every detail, as that would be too difficult and tediously long; so I’ll point out and compare/contrast a number of highlights. (Here is a link to the entire piano concerto, with a video of the score; move it ahead to about 18:50 to get to the fourth movement.)

ELP’s adaptation adds a considerable amount of material to Ginastera’s piece (as well as removing much of it), including of course the percussion section in the middle, as I mentioned above. Another addition is at the beginning, with Emerson playing a synthesizer, and Palmer hitting tympani.

Emerson plays a motif of B-flat, E, E-flat, and A, then Palmer hits A, A, A, and C. Then Emerson plays the same notes again, a bit faster, adding a C and an A, and Palmer does a short roll on A. Emerson goes up an octave to play the same first opening four notes, and Palmer does another, longer roll on A. Emerson, still in the higher octave, plays the notes faster, with the added C and A, and Palmer doesn’t another, still longer, crescendo roll on A.

Next, ELP’s adaptation converges with Ginastera, but with the latter’s arrangement of the B-flat, E, E-flat, and A motif played predominantly on horns, with all the notes sustaining in a swelling dissonance, while Emerson plays the notes on his synthesizer, intensifying the tension by adding a raspy, grating tone to it. The motif is played as I described above, then transposed an octave and a semitone higher to give B, F, E, and B-flat.

ELP come in with Emerson on organ, Lake on bass, and Palmer on drums. In Ginastera’s original, we hear pounding dissonances on the piano in 3/4=6/8 time, with the fourth bar in 5/8 time as an exception.

With the piano beginning in octaves of E in the bass, the orchestra is playing a cluster of eighth notes in A, B-flat, and E-flat. The E-flat goes up to a G-flat (with the E in the bass going down to a C-sharp with the G-flats), then back to E-flat, up and down and up and down. These movements up and down occur at irregular times, creating the illusion of odd time signatures, but Ginastera’s score has the whole passage in the same 3/4=6/8 time. The playing sounds fairly subdued in Ginastera’s original, but Emerson’s organ gives the passage a fiery extroversion.

The next passage has piano playing in the bass, whereas ELP’s version has Emerson playing it on synthesizer. A beginning in F and E leads to the opening motif of B-flat, E, E-flat, and A, then ending in another swelling dissonance reminding us of the opening one, but transposed a whole tone higher, giving us C, F, G-flat, and B (reverse the second and third notes to see the exact parallels). In Ginastera’s original, these notes are heard in the orchestra, predominantly the brass; in ELP’s version, Emerson does it on the synth, ending with that rasping sound again.

Next, a tune with a galloping rhythm, starting off with eighth notes going back and forth in F-sharp and A, then going to F-sharp, B, B-flat, C, A, F-sharp, and E, is heard on the strings; Emerson plays it on the organ. These seven eighth notes are heard three times, accented in a way that gives the listener the impression of 7/8 time, but again, Ginastera’s score notates it all as 3/4=6/8 time.

The up-and-down of F-sharp and A continues for a while, then we hear a five-note ostinato of B, A, F-sharp, E, and F-sharp, which grows dissonant with the addition of the horns, and ends with the piano playing a descension in octaves. ELP’s version ends the five-note ostinato, played on the organ, with more dissonant, angular synthesizer.

More of a galloping rhythm is heard in piano chords (on organ in the ELP version); this leads to more galloping, but with switches from 3/4=6/8 time to a bar of 5/8–this happens twice, then it returns to the regular 3/4=6/8 time. Again, what is piano in Ginastera is organ in ELP. Also, Ginastera’s version develops this switching of the time from six to five, while ELP’s version brings the tension to a climax with organ chords featuring a tritone of E and B-flat. Palmer also plays this tritone on the tympani.

Later on in Ginastera’s score, we hear a variation on the passage mentioned earlier, the cluster of repeated eighth notes, the top of which is the E-flat that goes up to the G-flat, then down, and up and down at irregular times. This time, however, the notes are a second-inversion A-minor triad with A-flat and C-flat in the bass. The top C-natural will go up to an E-flat, and down and up and down, in the same irregular pattern as with the E-flat and G-flat before. We hear the orchestra, predominantly strings, doing this; ELP’s version has the organ doing it.

After this, the piano does more galloping rhythms, with a few dissonant seconds thrown in here and there. Later, the piano does more developments of that passage with the time changes back and forth between six and five as discussed above, with an additional bar of 7/8 sandwiched in the middle. This passage isn’t in ELP’s version, which skips ahead in Ginastera’s score to bar 200.

Here, the galloping rhythm is done on pizzicato strings, starting with E-flat and G-flat going up and down in the bass clef. Then we hear E-flat, G-flat, A-flat, and A-natural three times before transposing the first two notes to A-natural and C. Emerson plays this line on the organ, but develops it further before going to the next passage.

A French horn plays A, D, G, and G-sharp, then A, E-flat, D, D-flat, G, and G-sharp, etc. Emerson plays this line on a synthesizer an octave higher. After this phrase, Ginastera has us hear five pairings of eighth notes of a minor second (C-sharp and D), with groupings of two to three eighth rests in between the first, second, third, and fourth pairings of those notes. They’re played softly in his score, but Emerson plays this rhythm as stabbing, loud organ dissonances.

A trumpet plays F, B, B-flat, and E three times; this leads to a climactic, dissonant passage. ELP’s version builds up this tension much more, right from the beginning of this passage, on the synthesizer. Ginastera does glissandi down and up on the piano; Emerson does a downward glissando on the organ.

At bar 240, the piano plays octaves in C, F-sharp, F-natural, and B, a restatement of the opening motif, but transposed up a whole tone; Emerson plays this on the synthesizer, using it to embellish the dissonance further and bringing this tensely climactic moment to raspy near-chaos, leading to Palmer’s percussion section. Ginastera’s original, however, further develops these themes on the piano, coming soon to the end of the movement.

Palmer pounds away on the tympani for a while, striking a gong here and there. This comes to an end, then we hear the soft hitting of A and C on the tympani, and on both tympani and tubular bells. Emerson plays three soft, dense chords on the piano as this passage comes to the end.

Next comes a passage with Lake playing electric guitar, with Palmer in the background hitting the tympani. Lake is playing, among other things, variations on that opening motif of sharpened tonic, fifth, flattened fifth, and tonic an octave higher.

The climax of the percussion section is Palmer showing off with a solo on his drum kit that features the drum synthesizer, and all the flashy, extraverted electronic sounds it can make.

After this, ELP ends their adaptation with a reprise of the section starting with A, D, G, G-sharp, etc. (i.e., the French horn line in Ginastera’s original). Again, Emerson intensifies the dissonant tension with that raspy synthesizer in ways totally different from the dissonant tension ending Ginastera’s original.

Both pieces end more or less the same way, with twelve sets of eighth notes of a dissonant chord played molto sforzatissimo, by the orchestra in the original, and on the organ in ELP’s version. The band played their recording of the adaptation for Ginastera in order to get his permission to publish it. The composer gladly gave it, describing ELP’s adaptation as “Diabolic!” and “Terrible!” These words were meant as compliments, though, for he felt that ELP had captured the mood of his music as no one else ever had.

That this music is “diabolic” makes it a perfectly dualistic contrast to the ‘piety’ of “Jerusalem.” Hence, we can see these two adaptations as thematically fitting within the context of Brain Salad Surgery as a whole. An outward appearance of trite piety masks the evil inside.

(Incidentally, a piece I composed years ago, my Divertimento for Strings, has a third movement, presto furioso, that is inspired by ELP’s adaptation of Ginastera’s toccata concertata, though I must insist that I used all my own notes and themes, not theirs. If you’re interested, please check it out.)

IV: Still…You Turn Me On

Lake was always sure to include an acoustic guitar ballad on every ELP album, and Brain Salad Surgery is no exception. Earlier, and in my opinion, far better examples of such ballads are “Lucky Man” and “From the Beginning.”

A curious thing about Brain Salad Surgery is how the musical style jumps all over the place. Normally, one tries to find a reasonably consistent style from track to track, but on this album, ELP seemed to be deliberately going as far in the opposite direction as possible. The album has a hymn, a violently modernist piece, a syrupy love ballad, a honky tonk piano farce, and a sci-fi epic–part standard prog, part jazz/piano sonata.

As far as I’m concerned, the only way to see unity in such musical and lyrical disunity is to hear it in terms of dialectical dualism, of finding a paradoxical unity in opposites. So, in these opening three tracks, we have the sentimentality (thesis) of Lake’s ballad, the brutal ugliness (negation) of the Ginastera adaptation, and the ironic piety masking evil (sublation) of the Parry/Blake adaptation. That Lake’s ballad is a love song also gives us the duality of male and female, some romanticized brain salad surgery? After all, he is turned on.

The instrumentation of the ballad reflects the man-vs-machine duality, in that on the one hand, we hear the human voice, Lake’s acoustic guitar, and Emerson’s harpsichord, but on the other hand, there’s Emerson’s synthesizer and Lake’s electric guitar leads played through a wah-wah pedal.

V: Benny the Bouncer

This song has lyrics written by Lake and Pete Sinfield, a colleague of Lake’s back when both of them were members of the original King Crimson back in 1969 and 1970. Lake would return the favour by helping Sinfield release his solo album, Still, on ELP’s new Manticore record label, as well as contributing vocals and electric guitar on it. Sinfield would also contribute lyrics to Side Two of Brain Salad Surgery, as we’ll soon see.

“Benny the Bouncer” manifests the album’s theme of duality in two ways: first, the use of synthesizer at the beginning, and the use of vocals and honky-tonk-style piano suggests the man-vs-machine motif; second, the light-hearted nature of the music, as juxtaposed with a story about a fight and a violent murder, gives us the duality of good vs evil, or light vs dark.

Benny is already understood to be a bloody, violent sort: “He’d slash your granny’s face up given half the chance,” as Lake sings in his affected Cockney. “Savage Sid,” however, is much meaner. First, he spills his beer on Benny’s boots to test him, then when the two fight, Sid sticks Benny with a switchblade, and Benny ends up with “an ‘atchet, buried in [his] head.” He’s dead now, and “he works for Jesus as the bouncer of St. Peter’s gate.”

All of this fighting, of course, is a reflection of the alienation found in an oppressive, dystopian society, the subject of the epic coming next, “Karn Evil 9,” the real thematic focus of Brain Salad Surgery.

VI: Karn Evil 9, 1st Impression

“Karn Evil” is a pun on carnival; this title for the sci-fi epic was suggested by Sinfield–due to the festive, carnival-like nature of the music heard in the “See the show!” sections of this movement, or “impression”–as a replacement for the originally intended title, “Ganton 9,” a fictional planet on which all evil and decadence has been put.

“Karn Evil” also reflects duality in the sense that the ‘carnival’ show of decadent displays is a pleasing, entertaining diversion (the ‘good’) from the evil and oppression really going on in this dystopian world. Indeed, this epic has real relevance in our world today, in the 2020s, in which such breads and circuses as the Super Bowl, Taylor Swift, OnlyFans, and photos of string-bikini-clad beauties plastered all over our Facebook feeds distract us from such problems as extreme income inequality, escalating wars, a media controlled by the super-rich, and the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

As for “9,” apart from “Ganton 9,” the meaning of this number could be seen in a subdivision into three of each of the three “impressions.” We all know, of course, about the division of the 1st Impression into two parts, because its length had to be spread over two sides of the original LP. One could, however, divide this impression further–namely, at the break between Lake’s singing of “Fight tomorrow!” and “Step inside, hello!”, or, between the frankly dystopian opening lyrics and the ‘carnival’ section about the “most amazing show.” Hence, three parts for the 1st Impression.

As for the 2nd Impression, it can easily be subdivided into three by virtue of its fast-slow-fast sections, like a short, three-movement piano sonata. The 3rd Impression can be divided in terms of the storyline as given by the lyrics: before the war, from the beginning to “Let the maps of war be drawn”; the middle, five-minute instrumental section and keyboard solo, as dramatizing the war; and the outcome of the war, from “Rejoice! Glory is ours!” to the end.

Anyway, part one of the 1st Impression begins with Emerson doing some contrapuntal playing on the organ. As Lake is singing the first verse, Emerson is playing dark, eerie bass notes on the piano while Palmer is hitting a cowbell.

This first verse establishes the dystopian world of the story, a dystopia disturbingly similar to our own world of the 2020s, “about an ago of power where no one had an hour to spare.” Those who have the power, the capitalist class, ensure that none of us, the working class, have much of any free time, because we’re all overworked and underpaid.

“The seeds have withered” because of environmental damage caused by prioritizing profit over the health of the planet. “Silent children shivered in the cold” because ‘free market’ capitalism has failed to provide for the needs of the poor, rendering so many of them homeless and unheard (“children” here isn’t necessarily to be taken literally; they can be also children in the metaphorical sense of being vulnerable and helpless).

The common people suffer like this because of “the jackals for gold,” or the greedy capitalists. “I’ll be there” to help when the revolution finally comes.

The working class have all been betrayed and silenced by the advocates of neoliberal, ‘free market’ capitalism (whose prophets, including the likes of Milton Friedman, were already making their promises of plenty in a world of ‘small government’ as of 1973, the year Brain Salad Surgery came out, thereby making “Karn Evil 9” prophetic, as I see it). The riot police of the ‘small government’ have “hurt…and beat” the people who try to protest the injustices they’ve been subjected to.

Everyone, working several jobs just to have enough to pay his or her bills, food, and rent, is “praying for survival,” but “there is no compassion” for those who cannot leave this miserable world–these are the homeless, whom it’s against the law to feed, and who suffer anti-homeless architecture and benches.

He, in whose voice Lake is singing, begs for a leader who will rise up and save the world from oppression, who will “help the helpless and the refugee”–that is, the impoverished and those displaced by war in ravaged places like Libya and Syria, or by genocide in Gaza. Again, he says he’ll “be there…to heal their sorrow.”

Next, we have the instrumental break that, in my opinion as described above, divides part one from the real part two of the 1st Impression (the “part two” of this impression beginning on Side Two of the LP being, in my opinion, ‘part three’ in actuality). We hear a tight riff in alternating 6/8 and 4/4, led by a synth melody; this tune will be heard again on Side Two in part two (or ‘part three,’ as I’d have it), but it will all be in 4/4.

This instrumental continues, with more time changes and synthesizer soloing, until it segues into the ‘carnival’ themes and ‘part two,’ as I conceive of it. Now that the dystopian world has been established, we will learn of how the powers-that-be are distracting the people from their oppression with “a most amazing show.” We can relate to this aspect of the story today, with all of the entertaining nonsense we see on TV and social media, distracting us from the horrors of the real world out there.

Those in power have always used two ways of keeping the masses under their control: the carrot and the stick, two seemingly opposed tactics, but actually just opposite sides of the same coin, since they both serve the same political purpose. The world government of Huxley‘s Brave New World uses the carrot of pleasure (sex, drugs, etc.) for social control, whereas the totalitarian government of Orwell‘s Nineteen Eighty-four uses the stick of coercion and bullying for the same purpose.

“Karn Evil 9” opens with an exposition of the dystopian stick, and with the “most amazing show,” we have the carrot. In our world, TV and social media are our carrot, meant to distract us from the stick of riot police and standing armies that imperialistically oppress the world. In cyclically abusive relationships, the carrot and stick represent traumatic bonding.

Those who “come inside” to “see the show” are the industrial working class, for they are told to “leave [their] hammers at the box” before going in. Among the images to see are violent, shocking ones, meant in this way to be entertaining and “spectacular”: namely, “rows of bishops’ heads in jars,” and a terrorist’s car bomb. The same goes for the “tears for you to see.”

There are entertaining horrors, but also entertaining pleasures, like the stripper. Of course, for many, the opium of the people is the most entertaining spectacle of all, hence they “pull Jesus from a hat.”

After all of this, there’s an instrumental section leading to the end of Side One of the LP. Being one of the pre-eminent progressive rock bands of the 1970s, ELP were always known for showing off their virtuosity as musicians, even to the point of annoying music critics, who accused them of egotism run rampant. For ELP to show off in this way, however, for the sake of putting on “a most amazing show,” is perfectly appropriate. In fact, Lake does some extended lead guitar soloing here, something he did only sparingly on previous ELP albums.

Side One ends with a fading-out of Emerson playing a repeated synth note in A-flat, accompanied by Palmer shaking a tambourine. This same music fades in to begin Side Two. There are CD versions of this music played without the fading out and in, giving an uninterrupted 1st Impression, but the long instrumental passage leading up to the famous “Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends,” still gives us the feeling that this is a distinct part two…or ‘part three,’ as I’d have it.

Note the ecological destruction alluded to in the line, “There behind the glass stands a real blade of glass.” While Lake is singing this line, Emerson comes in with the organ, playing that cheerful, ‘carnival’ music. In this we hear the stark contrast of the happy music masking the evil reality depicted in the lyrics of having wiped out almost all the plant life on the planet…and this horror is presented as a form of entertainment, or a museum piece.

In today’s world, the debate surrounding climate change could be seen as a form of entertainment, in that it may amuse many of us to watch and hear the heated, angry arguing over the controversy as to whether global warming is real or a myth. We go from “England’s green and pleasant land” to “a real blade of grass” over the space of one side of an LP.

So we can see how the theme of the good-vs-evil duality manifests itself as a mask in “Jerusalem” and “Karn Evil 9.” The piety and patriotism of the first track masks the “dark Satanic mills,” as discussed above, and the enjoyment of “the show,” the Karn of the carnival, its carnality, masks the Evil.

That the show is “guaranteed to blow your head apart,” in the context I just described, can thus have a dual meaning: good in that the show will impress and amaze us, and bad in that its mesmerizing effect will take away our ability to think independently. That we’ll “get [our] money’s worth” sounds like a capitalist hard-sell, and that “it’s rock and roll” suggests the decadence of capitalism (i.e., rock stars making huge profits while posturing as edgy, anti-establishment social rebels).

The decadence of rock is then aptly demonstrated by more instrumental showing-off, in this way by an organ solo by Emerson. This has to be one of the greatest organ solos in the history of art rock, ranking right up there with Rick Wakeman‘s organ solo on Yes‘s “Roundabout.” These solos almost compel fans to play ‘air organ,’ they’re so good.

Emerson’s organ playing here, as is the case with his piano playing in the 2nd Impression, is so good that it makes all the more tragic his suicide in 2016, from a gunshot wound to the head. Nerve damage in his right hand, starting in 1993, was hampering his playing; it had abated by 2002, but in 2016 he was struggling with focal dystonia, something he did not dare discuss publicly for obvious, professional reasons. Drinking and depression exacerbated the problem, and anxiety over performing badly, disappointing fans, pushed him over the edge, especially when internet trolls made mean comments about his playing. Lake died later the same year.

Speaking of Lake, after Emerson’s organ solo, he replays most of the written part of his guitar solo from Side One, followed by some extrovert drumming by Palmer and more verses. More references to decadence are made, these times of a sexual sort, when Lake sings of a “gypsy queen in a glaze of vaseline,” reminding us of the stripper from Side One; then there’s “a sight to make you drool–seven virgins and a mule.”

“The show” of the 1st Impression ends fittingly with more bombast, pomp, and instrumental showing off, particularly by Emerson playing fast notes on the synth, and by Palmer not only on the drums but also on the tympani.

VII: Karn Evil 9, 2nd Impression

This delightful instrumental has to be the creative zenith of the entire album, with “Toccata” and the 1st Impression just under it. Here, Emerson is held back by neither the need to play someone else’s notes, nor by a need to conform to listeners’ expectations, whether in the mainstream pop world, nor in that of what had by 1973 already become prog rock clichés. Here, we have pure Emerson as composer and artist, unfettered by anything.

Here‘s a link to the piece, with a transcribed score for piano and bass.

The piece begins with a long, twisting and turning piano riff, jazzy in style and yet, in the context of being sonata-like in structure, the ‘exposition,’ as it were. Palmer plays some fast, tricky drum licks before Emerson comes in as described, backed by Palmer and Lake on the bass. The music is modulating all over the place, and while most of it’s in 4/4, towards the end there’s a shift to a bar of 2/4, then two bars in 5/16, and a bar of 7/16 before returning to 4/4.

That long and winding piano riff is repeated, then there are two bars in 3/4, one in 12/16, one in 3/8, and one in 7/8 before going back to 4/4. After a while, we hear octaves on the right hand of the piano, eighth notes and sixteenth notes in C-sharp, then three sixteenth notes in E, then an eighth note in B, while on the left hand (doubled by Lake on the bass), instead of the E and B, it’s D and G respectively.

This set of notes is heard twice, leading into a section with a Latin American rhythm. Over this rhythm, Emerson plays a synthesizer solo that imitates the timbre of a steelpan. Palmer is shaking maracas and tapping claves in the background.

After this, a complicated riff is heard in alternating bars of 4/4 and 7/8 time, in the latter of which we hear high octaves in C-sharp on the right hand of the piano, thirds going up and down in C-sharp/E-sharp and D/F-sharp on the left hand, and C-sharp and D-natural on the bass. Next, a bar in 7/16, one in 9/16, and a 4/4 piano riff of high octaves in G-sharp, then C-sharp on the right hand of the piano, with the left hand playing second-inversion triads of E-natural/A-natural/C-natural to the right-hand G-sharp octaves, and left hand second-inversion triads of G-sharp/D-natural/F-natural to the right-hand C-sharp octaves.

The dissonance of these last few chords is the most tension we hear in this beginning fast section of the 2nd Impression, leading into the eerie tension of the slow middle section. Prior to this tense moment, the music has been largely upbeat and even merry. This contrast between cheerful and dark is once again a reflection of the good-vs-evil duality of “Karn Evil 9,” and of Brain Salad Surgery as a whole. Surface pleasures mask inner evils, as noted on previous tracks. The beginning fast section ends on a chord of C-sharp major.

While the beginning and ending fast sections are light and jazzy, the slow middle section is essentially like twentieth-century classical music in its use of eerie, atmospheric, dense chords, which are a kind of theme-and-variations form based on a harmonic progression in E minor, A minor, and C minor, as expanded tonality. As I said above, this softer music represents the hidden plotting and scheming behind the extrovert fun and games of the faster parts.

In this middle section, we hear Emerson’s expressive use of softer piano dynamics. Before, we heard his dabbling in jazz; now, we hear his mastery of classical technique.

Eerie, ambient, dense chords of G-sharp/D/E/A-sharp and F-natural/D/G-sharp/E are heard on the piano, and Lake follows with a line of A-sharp, G-sharp, F-natural, and E on the bass. These are heard twice, then Emerson plays intervals of G-sharp/E and F-natural/D, which Lake follows with a line of D, E, F-natural, G-natural, and A. This has all been in 6/4.

The time switches to 4/4, and Palmer is playing woodblocks behind the piano and bass, which have been playing harmonic variations of the chords and intervals I described above. At one point during this passage, Lake plays a descending chromatic line from E to A. Now in A minor, Emerson’s playing will include ascending and descending octaves in A, B, C-natural, and C-sharp, then C-natural, B, B-flat, and A; the first three of both sets of notes are triplets, and the second set of triplets are backed with a triplet roll on a kettledrum by Palmer, who’s still playing those woodblocks, like a ticking clock…ninety seconds to midnight (<<<more on this later).

The fast third section comes in next; it starts in 3/8 time, with Emerson playing a lot of fast triplets in the right hand. Then a bar of 4/8, back to 3/8 for four bars, a bar in 9/8, four more bars of 3/8, then 4/4, 4/8, 7/8, and a few more time changes until an improvisatory passage in 4/4.

In the middle of this passage, there’s a brief reprise of those dissonant chords heard just before the end of the fast first section, though notated in the transcription (YouTube link above, at about 6:16) with the enharmonic notes of D-flat octaves in the right hand, and a second-inversion triad of A-flat/D-natural/F in the left hand.

Finally, the 2nd Impression ends with a recapitulation, if you will, of the twice-played ‘exposition’ of the beginning of the fast first section, that twisting and turning theme. It ends with octaves in both hands of F-sharp on the piano, which Lake doubles on the bass.

VIII: Karn Evil 9, 3rd Impression

The music we hear Lake singing to sounds very patriotic, with a harmonic progression that sounds, to be perfectly frank, rather trite with, for example, its ending in a suspension fourth resolving to the leading tone, being the third of the dominant chord in the cadence, then back to the tonic in a major key.

How such music ties in with the story, it seems to me, is that a gung-ho, nationalistic attitude is being appealed to as a solution to the dystopian class conflict as established in the 1st Impression–trite harmony thus corresponds to patriotism as a naïve attitude in politics. Furthermore, historically such a solution has tended to lead to fascism, which in the context of this story can explain its ambiguous ending (more on that later).

Bourgeois liberal democracy gives the pretense of a free society, full of choice and pleasures, hence “the show” of the 1st Impression. But when class conflict gets too strained, as can be felt in the lyrics and music before the displays of the show, and the ruling class feels threatened by a proletarian uprising, they resort to fascism in order to maintain power, typically seducing the masses with talk of nationalism and patriotism, as is felt here in the 3rd Impression.

Once again, we have the duality of good as a mask for evil. The soldiers think they’re fighting for their country, when really they’re just fighting for the capitalist class.

“Man alone, born of stone”, is hard-hearted in his alienation. He thus is “of steel,” he’d “pray and kneel” to political and religious authorities to get an illusory sense of identity, communal inclusion, and meaning in his otherwise empty life. Still, his life is full of pain: “fear…rattles in men’s ears and rears its hideous head.”

Could that “blade of compassion” be the same blade of grass, the one preserved piece of plant life, from the 1st Impression? Whatever it is, it’s been “kissed by countless kings, whose jeweled trumpet words blind [men’s] sight.” Heads of state pretend to care about us, kissing compassion, as it were, and we’re blinded by the “jeweled trumpet words” of their demagoguery and false promises, believing their lies are truth.

We thought our civilization would last forever: “walls that no man thought would fall, the altars of the just, crushed…” Because of these disappointments, war must come, replacing the hope of revolution.

The relevance of the lyrics of the 3rd Impression to our world in the 2020s can be seen in not only the wish to fight the oppressive political system, but also in fascism’s co-opting of the common man to fight wars among nations instead of rising up in revolution against the ruling class, as well as how computers acting in their own right and supplanting humanity sounds like today’s rise of AI, and the fears many of us have about such technology replacing us in the working world and thus leaving us in abject poverty.

Accordingly, we sense hostility between man and machine (which, recall, is one of the main forms of the duality theme in Brain Salad Surgery–remember Giger’s ‘biomechanical’ album cover) in the bridge of the ship when the computer, voiced electronically by Emerson, says, “DANGER!…STRANGER! LOAD YOUR PROGRAM. I AM YOURSELF.” Indeed, our technology, in its quest to be dominant, is a reflection of ourselves.

All of these issues are relevant to our times in that we’ve seen these phenomena: a resurgence of fascist tendencies in many political movements in the world (those of Trump, Ukraine, Jair Bolsonaro, Marine Le Pen, Giorgia Meloni, etc.); such leftist struggles as Occupy Wall Street, opposition to the Gaza genocide, BLM, etc.; and the double-edged sword of AI (in a socialist context, where production is for providing for everybody’s needs, it can liberate us all; but in a capitalist context, it can throw millions of people out of work and thus subject us to homelessness, starvation, and death). Finally, a “nuclear dawn” in our time is the danger of such an armageddon between the US/NATO on one side, and Russia and China on the other.

All of what has come so far in the lyrics is a lead-up to war, culminating with “let the maps of war be drawn.” So the instrumental break, including a keyboard solo, all of it lasting for almost five minutes, represents the war.

There have been three interpretations of the outcome of the war. The first is that man has won, with Lake singing, “Rejoice! Glory is ours! Our young men have not died in vain.” Note the patriotic themes heard not only during the beginning of the middle ‘war’ section, but also during the beginning of this ‘victory.’

Perhaps man has deceived himself, though, in this supposed victory. Is the patriotic music a masking of an insidious evil, that of a surreptitious takeover of the computers? That they have won over man is the second interpretation of the war’s outcome. Such a possibility is suggested when the computer says to the “PRIMITIVE! LIMITED!” humans, “NEGATIVE!…I LET YOU LIVE.” In other words, the superior computers spared the defeated humans’ lives so they could see how inferior they are to their real victors. After all, “the tapes have recorded [the] names” of all the fallen men (suggestive not only of such things as the televising of the carnage of the Vietnam War, but also the deaths of so many in such places as Gaza today, all recorded on cellphones).

The third interpretation of the war’s outcome, as Sinfield–who collaborated with Lake on the lyrics of the 3rd Impression–would have us understand, is that man and the computers won together in a war against a shared enemy, but the computers have since taken control over man. Such an interpretation is the one most consistent with the lyrics, taking account of all of them.

IX: Conclusion

Such an interpretation is also conducive to the relevance of “Karn Evil 9” (and of Brain Salad Surgery as a whole) to our times in the 2020s. Class war was diverted from by fascism, not just in the period between the two world wars, but since both of them, too, in such forms as Operation Paperclip, with ex-Nazis working in the American and West German governments (including in NASA and NATO), in Operation Gladio, and in Western support for Ukrainian Nazi sympathizers all the way from the end of WWII to the present.

The war of the middle section of the 3rd Impression can thus be interpreted as the Cold War, with a preoccupation against “Un-American” activities as represented in the music by the patriotic theme. The perceived human victory would today be seen as the “end of history,” while the subsequent computer takeover can be seen to represent all of the technological advances of the three decades following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, including the online invasions of our privacy, AI threatening to take over many of our jobs, and the prospect of cashless societies making us helpless handlers of our cellphones.

So once again, the duality of good–for example, the convenience of new technologies–masks the evil of the hegemony of those technologies, just as the ‘good’ of patriotism masks the evil of fascism. In the same way, the piety and patriotism of “Jerusalem” mask the “dark Satanic mills,” and the erotic pleasure of ‘brain salad surgery’ and of “the show” masks the pain of “the helpless and the refugee.”

Contradiction and duality are at the heart of everything in life; this is what makes Brain Salad Surgery so thematically universal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.