I: Introduction

Salomé is an opera by Richard Strauss that premiered in 1905, the libretto being Hedwig Lachmann‘s German translation (with some editing by Strauss) of Oscar Wilde‘s 1891 French play. Wilde’s play, of course, was in turn inspired by the Biblical narratives in the Gospels According to Mark and Matthew.

Wilde transformed the brief Biblical story, making what’s implied explicit, namely how Salomé’s dance sexually aroused the Tetrarch Herod Antipas, elaborating on it as The Dance of the Seven Veils, considered by some to be the origin, however unwitting, of the modern striptease. Wilde also altered certain details, such as when, in the Biblical version, Herodias tells her daughter, Salomé, to demand the head of John the Baptist; instead, Wilde has Salome ask for “the head of Iokanaan” of her own accord.

Both Wilde’s play and Strauss’s opera caused scandals on their earliest performances, resulting in performances of them being cancelled or banned, for example in London, for many years. Now, Strauss’s opera is considered a masterwork, a regular part of any orchestral or operatic repertoire.

II: Quotes

Here are some quotes from Wilde’s play (some of which are not in Strauss’s opera), in English translation:

“How beautiful is the Princess Salomé to-night!” –Narraboth, the young Syrian, Captain of the Guard

“You are always looking at her. You look at her too much. It is dangerous to look at people in such fashion. Something terrible may happen.” –Herodias’ page

“How pale the Princess is! Never have I seen her so pale. She is like the shadow of a white rose in a mirror of silver.” –Narraboth

“The Jews worship a God that one cannot see.” –First Soldier

“After me shall come another mightier than I. I am not worthy so much as to unloose the latchet of his shoes. When he cometh, the solitary places shall be glad. They shall blossom like the rose. The eyes of the blind shall see the day, and the ears of the deaf shall be opened. The suckling child shall put his hand upon the dragon’s lair, he shall lead the lions by their manes.” –the voice of Iokanaan, heard from below, in a cistern

“What a strange voice! I would speak with him.” –Salomé, of Iokanaan

[Approaching the cistern and looking down into it.] “How black it is, down there ! It must be terrible to be in so black a hole ! It is like a tomb. . . . .” [To the soldiers.] “Did you not hear me? Bring out the prophet. I would look on him.” –Salomé

“Thou wilt do this thing for me, Narraboth, and to-morrow when I pass in my litter beneath the gateway of the idol-sellers I will let fall for thee a little flower, a little green flower.” –Salomé

“Oh! How strange the moon looks. Like the hand of a dead woman who is seeking to cover herself with a shroud.” –Herodias’ page

“Where is he whose cup of abominations is now full? Where is he, who in a robe of silver shall one day die in the face of all the people? Bid him come forth, that he may hear the voice of him who hath cried in the waste places and in the houses of kings.” –Iokanaan, having emerged from the underground cistern

“It is his eyes above all that are terrible. They are like black holes burned by torches in a tapestry of Tyre. They are like the black caverns of Egypt in which the dragons make their lairs. They are like black lakes troubled by fantastic moons. . . . Do you think he will speak again?” –Salomé, of Iokanaan

“Who is this woman who is looking at me? I will not have her look at me. Wherefore doth she look at me with her golden eyes, under her gilded eyelids? I know not who she is. I do not desire to know who she is. Bid her begone. It is not to her that I would speak.” –Iokanaan, of Salomé

“Speak again, Iokanaan. Thy voice is as music to mine ear.” –Salomé

“Back! daughter of Babylon! By woman came evil into the world. Speak not to me. I will not listen to thee. I listen but to the voice of the Lord God.” –Iokanaan, to Salomé

“Thy hair is horrible. It is covered with mire and dust. It is like a knot of serpents coiled round thy neck. I love not thy hair. . . . It is thy mouth that I desire, Iokanaan.” […] “There is nothing in the world so red as thy mouth. . . . Suffer me to kiss thy mouth.” –Salomé

IOKANAAN: Never! daughter of Babylon! Daughter of Sodom! Never.

SALOMÉ: I will kiss thy mouth, Iokanaan. I will kiss thy mouth.

“Cursed be thou! daughter of an incestuous mother, be thou accursed!” –Iokanaan, to Salomé

HEROD: Where is Salomé? Where is the Princess? Why did she not return to the banquet as I commanded her? Ah! there she is!

HERODIAS: You must not look at her! You are always looking at her! […]

HEROD: I am not ill, It is your daughter who is sick to death. Never have I seen her so pale.

HERODIAS: I have told you not to look at her.

HEROD: Pour me forth wine [wine is brought.] Salomé, come drink a little wine with me. I have here a wine that is exquisite. Cæsar himself sent it me. Dip into it thy little red lips, that I may drain the cup.

SALOMÉ: I am not thirsty, Tetrarch.

HEROD: You hear how she answers me, this daughter of yours?

HERODIAS: She does right. Why are you always gazing at her?

HEROD: Bring me ripe fruits [fruits are brought.] Salomé, come and eat fruits with me. I love to see in a fruit the mark of thy little teeth. Bite but a little of this fruit that I may eat what is left.

SALOMÉ: I am not hungry, Tetrarch. […]

THE VOICE OF IOKANAAN: Behold the time is come! That which I foretold has come to pass. The day that I spoke of is at hand.

HERODIAS: Bid him be silent. I will not listen to his voice. This man is for ever hurling insults against me.

HEROD: He has said nothing against you. Besides, he is a very great prophet. […]

A THIRD JEW: God is at no time hidden. He showeth Himself at all times and in all places. God is in what is evil even as He is in what is good.

A FOURTH JEW: Thou shouldst not say that. It is a very dangerous doctrine, it is a doctrine that cometh from Alexandria, where men teach the philosophy of the Greeks. And the Greeks are Gentiles: They are not even circumcised. […]

FIRST NAZARENE, of Jesus: This man worketh true miracles. Thus, at a marriage which took place in a little town of Galilee, a town of some importance, He changed water into wine. Certain persons who were present related it to me. Also He healed two lepers that were seated before the Gate of Capernaum simply by touching them. […]

THE VOICE OF IOKANAAN, of Herodias: Ah! the wanton one! The harlot! Ah! the daughter of Babylon with her golden eyes and her gilded eyelids! Thus saith the Lord God, Let there come up against her a multitude of men. Let the people take stones and stone her. . . .

HERODIAS: Command him to be silent.

THE VOICE OF IOKANAAN: Let the captains of the hosts pierce her with their swords, let them crush her beneath their shields. […]

HEROD: Dance for me, Salomé.

HERODIAS: I will not have her dance.

SALOMÉ: I have no desire to dance, Tetrarch. […]

HEROD: Salomé, Salomé, dance for me. I pray thee dance for me. I am sad to-night. Yes; I am passing sad to-night. When I came hither I slipped in blood, which is an evil omen; also I heard in the air a beating of wings, a beating of giant wings. I cannot tell what they mean . . . I am sad to-night. Therefore dance for me. Dance for me, Salomé, I beseech thee. If thou dancest for me thou mayest ask of me what thou wilt, and I will give it thee, even unto the half of my kingdom.

SALOMÉ: [Rising.] Will you indeed give me whatsoever I shall ask of thee, Tetrarch? […]

HEROD: Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, even unto the half of my kingdom.

SALOMÉ: You swear it, Tetrarch?

HEROD: I swear it, Salomé. […]

SALOMÉ: I am ready, Tetrarch. [Salomé dances the dance of the seven veils.]

HEROD: Ah! wonderful! wonderful! You see that she has danced for me, your daughter. Come near, Salomé, come near, that I may give thee thy fee. Ah! I pay a royal price to those who dance for my pleasure. I will pay thee royally. I will give thee whatsoever thy soul desireth. What wouldst thou have? Speak.

SALOMÉ [Kneeling]: I would that they presently bring me in a silver charger . . .

HEROD [Laughing]: In a silver charger? Surely yes, in a silver charger. She is charming, is she not? What is it thou wouldst have in a silver charger, O sweet and fair Salomé, thou art fairer than all the daughters of Judæa? What wouldst thou have them bring thee in a silver charger? Tell me. Whatsoever it may be, thou shalt receive it. My treasures belong to thee. What is it that thou wouldst have, Salomé?

SALOMÉ [Rising]: The head of Iokanaan.

HERODIAS: Ah! that is well said, my daughter.

HEROD: No, no!

HERODIAS: That is well said, my daughter. […]

“You have sworn an oath, Herod.” –Salomé

“Well, thou hast seen thy God, Iokanaan, but me, me, thou didst never see. If thou hadst seen me thou hadst loved me. I saw thee, and I loved thee. Oh, how I loved thee! I love thee yet, Iokanaan, I love only thee. . . . I am athirst for thy beauty; I am hungry for thy body; and neither wine nor apples can appease my desire. What shall I do now, Iokanaan? Neither the floods nor the great waters can quench my passion. I was a princess, and thou didst scorn me. I was a virgin, and thou didst take my virginity from me. I was chaste, and thou didst fill my veins with fire. . . Ah! ah! wherefore didst thou not look at me? If thou hadst looked at me thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater that the mystery of death.” –Salomé, holding and gazing upon the severed head of Iokanaan

“She is monstrous, thy daughter I tell thee she is monstrous.” –Herod, to Herodias

“Ah! I have kissed thy mouth, Iokanaan, I have kissed thy mouth. There was a bitter taste on my lips. Was it the taste of blood ? . . . Nay; but perchance it was the taste of love. . . . They say that love hath a bitter taste. . . . But what matter? what matter? I have kissed thy mouth.” –Salomé, still with Iokanaan’s head

HEROD: [Turning round and seeing Salomé.] Kill that woman! [The soldiers rush forward and crush beneath their shields Salomé, daughter of Herodias, Princess of Judæa.]

III: Themes and Beginning

Recurring themes in the play/opera include these: lust, with gazing/leering/staring at the object of desire, hence objectification; the conflict between, and complementarity of, opposites (love/loathing, spirituality/carnality, desire/disgust, white/black, male/female roles, beauty/ugliness, life/death, victim/victimizer, etc.); and the decadence of the ruling classes, as against the assurances for the oppressed that revolution, redemption, and liberation are soon to come.

The story begins at night, just outside a banquet held by Herod, his wife, Herodias (widow of his half-brother, Herod II), and her daughter, Salomé, along with all their guests in Herod’s palace. The moon is shining, silvery-white and bright. Silvery-white because, as Narraboth says, “She [the moon] is like a little princess…whose feet are of silver,” and “who has little white doves for feet.”

Narraboth, a young Syrian and Captain of the Guard, amorously declares how beautiful Salomé looks. The Page of Herodias wishes he wouldn’t always stare at her, for the Page fears that disaster will come of his passion.

The moon is a pale, virgin, silvery white, as is Salomé’s flesh. The moon looks so pale and white, “She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman,” as the page of Herodias observes.

The princess-moon, with her innocent white feet, can drive men lunatic, as can Salomé’s virginal beauty; as, in turn, the holy purity of similarly-pale Iokanaan drives her mad with love for him. In this play, virginal innocence is dialectically related to the deadly sin of lust: the one opposite dissolves into the other.

IV: Enter Salomé

Salomé leaves the banquet area, finding it disturbing how Herod keeps staring at her with lust in his eyes. Of course, Narraboth is eyeing her similarly, but she will soon be an ogler herself, for she hears the voice of Iokanaan from the cistern below.

He has spoken harsh words against her mother, Herodias, as well as against Herod (i.e., his incestuous marriage with his half-brother’s widow); Salomé knows of this, but instead of being offended by Iokanaan’s words, she’s intrigued. It seems evident that Salomé has hardly any less contempt for her mother than she does for her adoptive father: alienation, including that between family members, is a typical symptom in a world of class conflict, in this case, that of the ancient slave vs. master variety.

Thus, any speaker of ill against Salomé’s family is a singer of sweet music to her ears. Small wonder she’d like to take a look at that mysterious man down in that dark, yonic pit. She looks down into it, awed by its darkness. This blackness, of course, is associated with Iokanaan’s mysticism. An ominous, eerie tritone is heard in the musical background when she looks into the cistern and notes its blackness, near the beginning of scene two.

Let’s compare some images used so far. Pale Salomé is consistently associated with the silvery-white, virginal moon, an ominous orb portending imminent evil. The cistern is black, as Salomé observes, but since it houses a holy man, a celibate man, it could be seen as virginal, too, the yoni of a virgin such as Salomé herself. The cistern’s blackness thus has a dialectical relationship with the silvery-white moon, which phases from white full moon to black new moon, and back again. Iokanaan, like the moon, also portends an evil coming too soon for comfort.

She insists on having Iokanaan brought out so she can see him, to have his mysteries revealed…just as Herod will want Salomé to dance a striptease for him, to reveal her anatomic mysteries. The lecherous, decadent tetrarch, of course, also hopes to make the young beauty replace her mother as his new queen, so her virginal yoni‘s dark secrets can be revealed to him…just as she wishes to have Iokanaan, the secret of the dark yoni of the cistern, revealed to her eyes.

The parallels between Iokanaan’s display and that of her nakedness continue, first with Narraboth’s and the soldiers’ insistence that the prophet not be allowed out (by Herod’s orders), on the one hand, and Herodias’ disapproval of her daughter dancing erotically for Herod. Also, Salomé entices Narraboth with suggestions of her favouring him (offering a green flower and a smile) if he’ll allow Iokanaan to come out, and Herod entices her with an oath to give her anything she wants if she’ll dance for him. Both Narraboth and Salomé are persuaded to do what they’d otherwise never do.

V: Enter John the Baptist

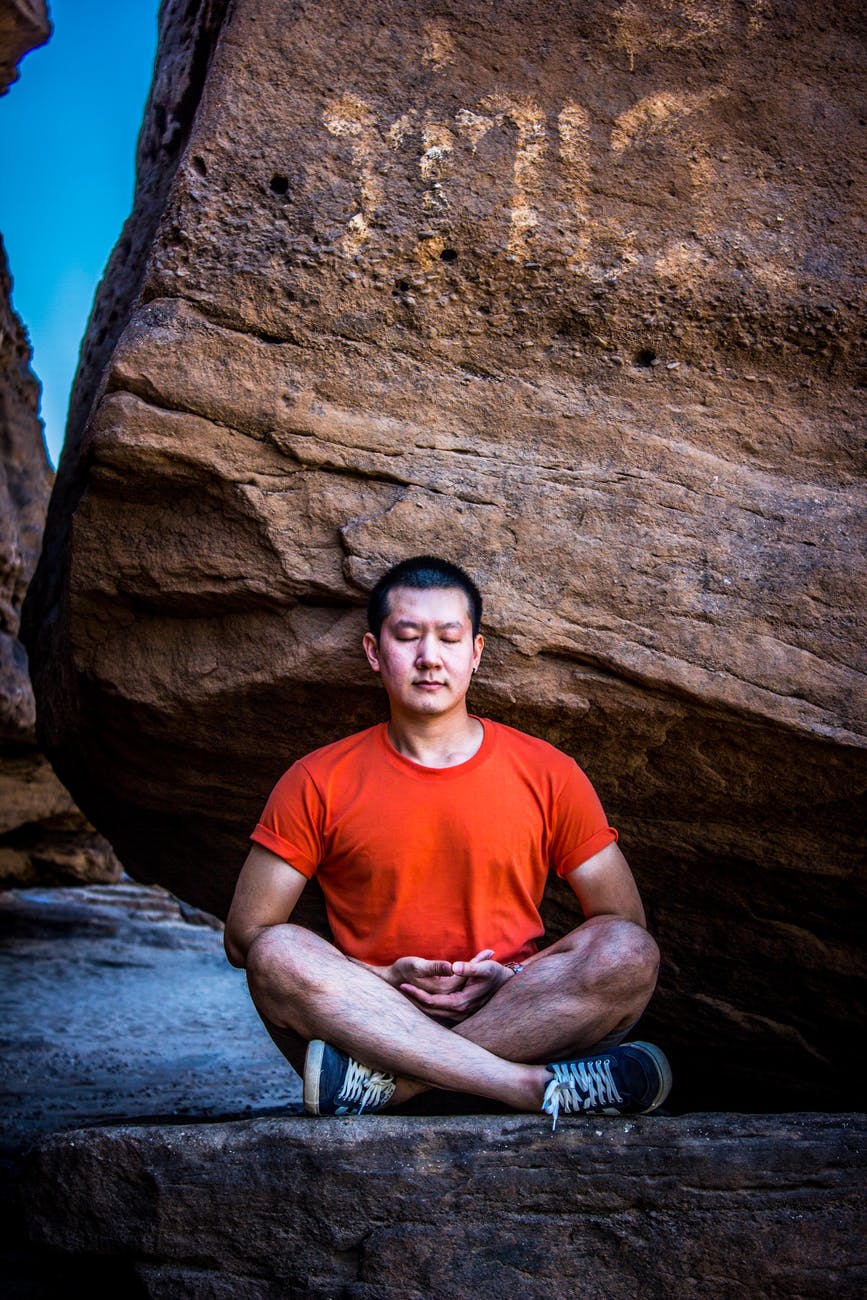

Iokanaan emerges from the cistern, pale, hairy, and filthy, but always shouting his imprecations against the decadent kings and queens of the world, especially Herodias. His holiness inspires Salomé’s passion for him, symbolizing the dialectical relationship between the erotic and the ascetic (something also explored in Hindu myth, as Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty observed in Siva: the Erotic Ascetic, pages 33-36).

At first, Salomé loves Iokanaan’s white flesh, a parallel of the love Narraboth and Herod have for her pale flesh. The prophet, of course, rejects her wish to touch his body; indeed, he can’t even bear to have this “daughter of Sodom” look at him. She’s angered by his rejection, feeling narcissistic injury, no doubt; but his chastity fascinates her all the same.

Salomé is used to having a train of admiring men following her everywhere, leering at her, lusting after her. Such men bore her, annoy her, inspire her contempt; but Iokanaan is no lecherous pig. With him, the sexes are reversed, and the man is disgusted with the woman’s lechery. She’s hurt by his rejection, but she can only admire him all the more for it. This man’s spiritual willpower is as rare as her physical beauty is, and her desire for him is made all the hotter for this.

As soon as he rejects her, she speaks ill of his whitest of white body, which she’s just finished praising. Now she speaks of loving his blackest of black hair; note the immediate juxtaposition of opposites–loved/loathed, beautiful/ugly, and white/black. When he rejects her wish to touch his hair, she’s now repelled by it and begins loving his red lips.

VI: Baiser

She wants to kiss his mouth, saying in Wilde’s French: “Laisse-moi baiser ta bouche.” Baiser, as a verb, originally meant ‘to kiss,’ but it grew to mean ‘to fuck,’ this new meaning starting as early as the 16th or 17th century, having been used this way in, for example, a few poems by François Maynard. This usage began to grow more common by the beginning of the 20th century, prompting the French to start using embrasser to mean ‘to kiss’ instead.

My point is, given the already shockingly erotic overtones of Wilde’s play, as well as in his choice to write it in French instead of his usual English, did he use baiser as a double entendre? Was he suggesting a secondary meaning, a cunnilingus fantasy of Salomé’s, to get head from Iokanaan?

Now Strauss, in using a German translation for his opera, used the word küssen, which only means ‘to kiss.’ Perhaps he was aware of the growing use of the sexual meaning of baiser, and wanted to mitigate the scandal by eliminating that problematic French word. I’m guessing that my speculations hadn’t been discussed by critics back around the turn of the 20th century, given the-then taboo nature of this subject; but this taboo use of baiser has been discussed more recently.

VII: Lustful Staring

Back to the story. The prophet is so shocked by this “daughter of Babylon” that he curses her and goes back down into the cistern. Salomé’s unfulfillable desire has turned into an obsession; speaking of which, Narraboth’s has caused him to implode with sexual jealousy, since he can see she clearly prefers Iokanaan to him. Thus, he stabs himself and dies, fulfilling Herodias’ page’s dire prediction that his obsessive, mesmerized staring at Salomé would bring evil.

Of course, the young Syrian hasn’t been the only one staring at Salomé to the point of such ogling being dangerous. Herod enters with Herodias; he slips on Narraboth’s spilled blood, an obvious omen.

The tetrarch speaks of the silvery-white moon and Salomé’s pale skin, an evident identifying of the one with the other, just as Salomé has identified the chaste moon with celibate Iokanaan. We see more unions of opposites: virginity and whorish objects of desire, in both her and the prophet.

Herodias is annoyed with Herod’s staring at her daughter, with Iokanaan’s insulting diatribes against her, and Herod’s–to her, absurd–belief in omens and prophecies. She is a purely materialist, decadent queen: the moon is just the moon to her.

She wishes he would just give Iokanaan over to the ever-disputatious Jews, who come out and begin a clamorous storm of debating over whether Iokanaan has seen God, whether he is Elijah having returned, and whether this or that dogma is correct. This is another example of wanting to know mysteries, to see secrets.

In all of this arguing among the Jews, we see dramatized the dialectic of contradictory viewpoints. Added to this is the contradiction between the Jewish point of view and that of the Nazarenes, who now come onstage.

VIII: Revolution

Since the Crucifixion hasn’t happened yet, discussion of how the Messiah will save the Jews from their sins is never in the Pauline notion of a Divine Rescuer dying and resurrecting, so that believing in Him will confer God’s grace for the forgiveness of sins. Instead, salvation for the Jews is understood to come in the form of a revolution against Palestine’s Roman imperialist oppressors. Recall Matthew 10:34.

Revolution! Insurrection! Such words terrify decadent rulers like Herod and Herodias, who naturally don’t want to lose their privileges as members of the ruling class. Thus do we see the dialectic move, from the Hegelian sort we heard among the debating Jews, to the materialist sort that Marx discussed: the contradiction between the rich and poor.

Iokanaan prophesies the downfall of sinful rulers like incestuous Herod and Herodias, as well as the redemption of the downtrodden. As the prophet says at the beginning of Wilde’s play, “the solitary places shall be glad. They shall blossom like the rose. The eyes of the blind shall see the day, and the ears of the deaf shall be opened. The suckling child shall put his hand upon the dragon’s lair, he shall lead the lions by their manes.”

Such welcome changes can be seen to symbolize revolutionary relief given to the suffering. The blind seeing, and the deaf hearing, suggests the enlightenment of the poor, hitherto ignorant of the true causes of their sorrows. The idea of gladdened solitary places suggests the replacement of alienation with communal love. The suckling child, with his hand on the dragon’s lair, and leading the lions, suggests the end of the oppression of the weak by the strong, replacing it with equality.

Marx similarly prophesied the end of the rule of the bourgeois, to be replaced by communist society. The bourgeois today, like threatened Herod and Herodias, are scared of their imminent downfall, for many believe their days are numbered.

My associating Iokanaan with Marx is no idle fancy, for in 1891, the very same year Wilde wrote Salomé, he also wrote The Soul of Man under Socialism, inspired by his reading of Peter Kropotkin, and in which Wilde considered Jesus to be a symbol of the extreme individualist he idealized. Wilde would also have been aware of the short-lived Paris Commune twenty years prior, which Marx joyfully described as being a manifestation of his notion of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

IX: The Music

It seems apposite, at this belated point, finally to discuss Strauss’s music. Influenced by Wagner’s musical dramas, Strauss used Leitmotivs (“leading motives”) for each character in Salomé, as well as for many key moments or concepts in the story.

There’s the light, dreamy Leitmotiv heard when Narraboth expresses his admiration for Salomé’s beauty at the beginning of the opera. There’s the Leitmotiv when she sings of wanting “den Kopf des Jochanaan,” which gets increasingly dissonant with her every iteration of the demand for it, to ever-reluctant Herod.

And there are Leitmotivs for Iokanaan and his prophetic abilities, the former being a stately, dignified chordal theme heard on the horns; and the latter melody being a trio of fourths, C down to G, then F down to C, then–instead of another, third perfect fourth–there’s a tritone of A down to D-sharp, then up to E, now a perfect fourth (relative to the previous A). These three sets of perfect fourths symbolize Triune, holy, divine perfection; the tritone, though the diabolus in musica, nonetheless resolves to E, symbolizing a prophecy of sinning imperfection soon to be made perfect, redeemed.

Strauss, as a late Romantic/early modern composer, anticipated many of the revolutionary musical ideas soon to be realized in full by such modernists as Stravinsky, Bartók, Schoenberg, and Webern. Strauss was thus a kind of musical Iokanaan. Strauss, through his extreme chromaticism, pushed tonality to its limits, while not quite emancipating the dissonance, as Schoenberg would soon do. Since some have seen the emancipation of the dissonance as linked with the emancipation of society and of humanity, the music of Strauss–as musical Iokanaan–can be seen symbolically as heralding the coming of that social liberation I mentioned above.

The harsh discords in his score symbolize the contradictions not only in the class conflict between the decadent rulers (puppet rulers for imperial Rome) and the oppressed poor, but also in the conflicts between what Narraboth, Salomé, Iokanaan, Herod, and Herodias each wants. Also, the contrast between these dissonant moments and the prettier, more tuneful sections suggests the dialectical relationships between beauty and ugliness, and love and loathing.

Finally, the choice of ‘harsh‘ (at least from the point of view of English speakers), guttural German–instead of Wilde’s erotically lyrical (if a tad idiosyncratic) French–reinforces the dramatic tension, especially when Salomé demands the prophet’s head on a silver charger.

X: Dance for Me, Salomé

Back to the story. Herod is so obviously troubled, on the one hand by the threats Iokanaan is making against his rule, and on the other by his fear of the prophet as a man of God–which means he can’t kill him–that the soldiers note the tetrarch’s sombre look.

Herod hopes that Salomé will dance for him, to take his mind off his troubles. This escape into sensuous pleasure is an example of the manic defence, to avoid facing up to what makes one so unhappy.

Always annoyed that her husband stares lustfully at her daughter, Herodias forbids Salomé to dance for him. But his oath to give her anything she wants, even to half of his kingdom, puts a sly grin on her face and a twinkle in her eye; so Salome agrees to dance.

Wilde‘s brief stage direction, of Salomé dancing in seven veils, has been made so much of. It says nothing explicitly of a striptease, but why else would she dance in those veils, if not to remove them one by one?

Strauss’s exotic, sensuous music certainly makes much of the dance, starting with a slow, erotic, mysterious aura and building up to a fast, frenzied, and dissonant climax, once almost all (or absolutely all, depending on the boldness of the woman playing Salomé) of the veils have been removed.

XI: Getting Naked

As each veil is removed, more of the mysteries of her body are revealed to horny Herod, just as the mystery of Iokanaan was revealed to lascivious Salomé when he emerged from the vaginal cistern. This story is all about the desire to have secrets revealed, including, as the Jews obsess over, the mysteries of God, through such things as prophecies, as the Nazarenes are concerned with. Mysteries thus may be sensual or spiritual: note the dialectical relationship between these two.

While we usually think of men objectifying women, as Herod is doing with Salomé here, in Salomé the objectifying is a two-way street, since she lusts after chaste Iokanaan. And while it is usual and correct to be concerned with the injuries done to female strippers, sex workers, and pornographic models and actresses, consider how pathetic the men are, those addicted to porn, prostitutes, and strippers, using these as a manic defence to avoid facing their own sadness. Consider their shame at knowing what pigs they’re being (or at least seen as being), each a modern Herod, walking guiltily in and out of strip joints, whorehouses, and the porn sections of DVD rentals.

There are two sides to objectification: the view to destroy, as Salomé does to Iokanaan, and as Herod does to Salomé at the end of the opera; and there’s the view to admire, to worship the beautiful object, as any connoisseur of art understands…and as Salomé and Herod also do to their adored objects. Looking to admire and to destroy are, again, dialectically related. This obsessive urge to look, a pagan adoration of divinity that is–in this opera–thematically related to whether or not the Jew or Nazarene has ‘seen’ God, is also a weakness that can be exploited.

Salomé is certainly using her sexuality to take advantage of this weakness of Herod’s. And since, on the one hand, the tetrarch is objectifying and using her for his pleasure, getting her to strip down to a state of nude vulnerability; and on the other hand, she’s turning his lust against him, we have here a male/female variant of Hegel‘s master/slave dialectic, or a dialectic of feminism meeting antifeminism.

XII: Switching Roles

The master (Herod) uses the, so to speak, slave (Salomé) for his own pleasure, but she uses her creativity (her dance) to build up her own mastery over him. Thus, master and slave switch roles, making her especially triumphant, since she’ll cause the doom of two men–decapitated Iokanaan, and the revolutionary toppling of Herod, as it is assumed will happen to him when the Nazarenes (and God!) are so enraged to learn of the execution of their beloved prophet.

Women are perceived to be inspiring of lust and sin (the misogynistic, antifeminist side of the dialectic), yet Salomé and Herodias triumph in thwarting the tetrarch and killing the male religious authority (the feminist side). What’s more, Salomé is all the more feminist in wishing for Iokanaan’s head for her own pleasure, not out of obedience to her mother.

Herod pleads with Salomé to ask for something else. The tetrarch has made himself a slave to his oath, of which she’s the master. He offers her rare jewels, ones even her mother doesn’t know he has; he offers her rare white peacocks. All she does is repeat her demand for “den Kopf des Jochanaan,” each time given more and more aggressively, with increasingly tense music in the background. Finally, he is forced, in all exasperation, to relent.

XIII: The Head

When the executioner is down in the dark cistern, Salomé waits by the hole and listens. Suspense is built when she hears nothing. She grows impatient, thinking she’ll need the soldiers to do the job she imagines the slave who went down with his axe is too incompetent or cowardly to do. Nonetheless, he emerges with Iokanaan’s bloody head. The ruling class’s indulgence of their petty desires always brings about violence of this sort.

Still, there are contradictions even among the desires of the different members of the ruling class. Herod is horrified to see Salomé’s maniacal gazing at the head, but Herodias is pleased to no end. Salomé kisses the mouth, triumphant in having achieved what the living prophet refused to let her do. In her mania, she imagines for the moment that Iokanaan’s eyes should be looking at her, as if the severed head could possibly be alive. She is thus disappointed that the eyes don’t look at her.

She wishes that he could have accepted her love, that if he’d looked at her, that if he’d just let her kiss his mouth, he would have loved her back, for love is a greater mystery than death.

XIV: Decapitation as Symbolic Castration

Since Wilde’s use of baiser has the implied secondary meaning of “to fuck,” and since she says, “Ah! thou wouldst not suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Jokanaan. Well! I will kiss it now. I will bite it with my teeth as one bites a ripe fruit. Yes, I will kiss thy mouth, Jokanaan,” she is implying that she has a symbolic vagina dentata, which will castrate him when they make love. She compares his body to a column of ivory, a column being a phallic symbol. Thus, ‘fucking’ his mouth with the implied vagina dentata means his decapitation is a symbolic castration.

Herod’s unwillingness to have Iokanaan beheaded is thus an example of castration anxiety, especially since loss of the phallus is a symbolic loss of power. Herod’s fear of Iokanaan’s execution provoking a Nazarene revolution, spearheaded by none other than God, reinforces this symbolic fear of castration. Iokanaan’s “Kopf” is a cock.

XV: Conclusion–Who Wins the Sex War (and the Class War)?

Salomé (and by extension Herodias, since she has wanted Iokanaan’s death from the beginning), having the prophet’s head in her arms, is now symbolically the powerful phallic woman. She, especially in her madness and perversity, is a threat to Herod. Regarding her as “monstrous,” he orders all the torches to be put out. He says, “Hide the moon! Hide the stars!” For the whiteness of the moon and stars resemble her pale skin far too much for his comfort.

Finally, the male/female dialectic sways back in the antifeminist direction, and Herod orders his soldiers to “Kill that woman!” The men surround Salomé with their shields, and crush her to death with them, ending the opera with a barrage of discords.

Still, we know that the days of all decadent kings and queens–as well as those of the tetrarch, it seems–are numbered. Herod is still quaking in fear over the consequences of killing a holy man. The Nazarenes believe the tetrarch cannot stop the march of God through history, just as we Marxists believe the bourgeoisie cannot stop the dialectical movement of historical materialism.

Herod can hide the moon and the stars for only so long. Recall Iokanaan’s words: “In that day the sun shall become black like sackcloth of hair, and the moon shall become like blood, and the stars of the heaven shall fall upon the earth like unripe figs that fall from the fig-tree, and the kings of the earth shall be afraid.”

Furthermore, Salomé may be dead, but her double, that pale moon overhead, is still shining. In his poem, ‘Problems of Gender,’ Robert Graves wondered which gender to assign the moon, asking, “who controls the regal powers of night?” In Salomé, I think we know which sex controls them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.