I: General Introduction

Discipline (1981), Beat (1982), and Three of a Perfect Pair (1984) are three King Crimson albums that I feel ought to be analyzed together, as they all share common themes, which I’ll go into later.

This era in King Crimson’s history has a number of firsts. Here, guitarist/leader Robert Fripp and drummer Bill Bruford are joined with guitarist/singer/lyricist Adrian Belew and bassist/Stick-player/back-up vocalist Tony Levin, both Americans, making this the first time that the mighty Crims were no longer 100% British.

On these three studio albums, we have, for the first time, the exact same lineup consecutively. Previously, the band had experienced everywhere from the loss of one member to a changing of all of them (except Fripp). The instability of the band had been at its worst between their first two albums and their fourth, Islands, during which time the abilities of the band members had gone from their strongest to their weakest (i.e., Boz Burrell was a good singer, but since Fripp had had to teach him bass, his playing wasn’t as precise as that of the others). In this fully stable 1980s lineup, though, King Crimson was made up of four of the top musicians in the entire world.

There were major changes in instrumentation, too. The Mellotron, an important part of their early sound, is absent from the 1980s on. Given how obsolete the keyboard had become in a world with polyphonic synthesizers that would increasingly be able to imitate conventional instruments, as well as how difficult the Mellotron is to maintain (recall Fripp’s quip that “tuning a Mellotron doesn’t”), it’s easy to see why it wouldn’t be used anymore; still, some fans of the old King Crimson found the instrument’s absence conspicuous. Instead, the new sound would highlight the then-new technology of guitar synthesizers, the Chapman Stick, and electronic drums. The Crims would be the band of the future…with a second guitarist who sang lead vocals instead of the bassist, and who consistently wrote the lyrics instead of there being a separate lyricist, like Peter Sinfield or Richard Palmer-James.

With all these changes in instrumentation (no more saxes, flute, or violin, either) also came radical changes in musical style. The new band fused new wave, minimalism, African polyrhythms, and even Balinese gamelan music with their usual progressive rock sound. Belew’s spoken-word contributions reinforced the new American sound, and his extroverted guitar wailing, with its imitation of animal noises, made seated Fripp seem even more introverted, him being content often to play his repeated guitar lines in the background.

Of course, this wasn’t the first time that King Crimson had made a significant change in their musical direction. The change from their pretty, dainty, jazz-tinged sound on their first four albums to their harder-rocking, improvisational sound during the John Wetton years deserves note. This change to an almost Talking Heads style in the 1980s, though (easy to hear, since Belew had just played with the Heads prior to the formation of this new Crimson, and he was occasionally criticized for seeming to be a David Byrne clone–the spoken word stuff), was far more radical.

So these were the musical aspects of the new band, as described in large brush strokes. Now, I’ll go into the recurring themes that I find in the lyrics of these three albums, for now described generally.

A hint as to what these themes are can be found in the album cover designs of the three albums. All three follow a similar format: the same font for the lettering, a symbol of some kind in the centre (or top-centre, as is the case with Beat), and a primary colour for the background–minimalist art for minimalist music. Red was the colour for Discipline, with a chain symbol; blue for Beat, with a pink eighth note; and yellow for Three of a Perfect Pair, with blue arches representing phallic and yonic symbols…and on the back cover, added to these two is a red arch “drawing together and reconciling the preceding opposite terms,” according to Fripp.

Note that we have not only three albums, but a third whose cover suggests that its…overarching [!]…theme is a sublation of the preceding two elements, the ‘perfect pair.’ The dominant themes of Discipline and Beat, implied by their titles, is an opposition between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. It should be easy to see the ideal of Apollo in the act of discipline; since Beat is greatly inspired by the Beat Generation writers (e.g. “Neal [Cassady] and Jack [Kerouac] and Me”), who were known for such things as wild drunken parties, free love, and the use of illicit drugs, it should be easy to associate Beat with Dionysus.

Thus, in the three albums, we can see and hear the Hegelian dialectic of thesis (Discipline), negation (Beat), and sublation (Three of a Perfect Pair). I will now go into how this is true, detail by detail.

II: Discipline

Here is a link to the lyrics for the album.

Elephant Talk

Levin begins the song with an accelerating tapping of two tritones–C/F-sharp and D/G-sharp–on the Stick, and these tritones will be featured in the funky main riff of the song. When the rest of the band comes in, Fripp will be mostly playing quick A minor arpeggios, and during the moments when Belew is making elephant noises on his guitar, Fripp is playing arpeggios in F-sharp.

As far as the lyrics are concerned, we find a basic exposition of the theme of the dialectic, with words like “arguments, agreements,” that suggest agreements with the thesis and arguments between the thesis and its negation. The “contradiction, criticism,” and “bicker, bicker, bicker” also indicate the conflict between the thesis and negation.

The basic idea behind any dialectic in philosophy is that it is a “dialogue, duologue” between two disagreeing people who, in their “debates, discussions” are searching to find the truth through reasoned discussion. “Talk, talk, it’s only talk.”

Now, there is a discipline in improving one’s philosophical thought through the use of the Hegelian dialectic. One mustn’t have a biased attachment to one’s thesis: it must be challenged with the negation’s “commentary, controversy” as well as its “diatribe, dissension” and “explanations.”

When one keeps the best parts of the thesis, while acknowledging the objections and qualifying of the negation, a sublation is achieved, a refining of one’s ideas, an improvement on them. One doesn’t stop there, though, for the sublation becomes a new thesis to be negated and sublated again. This three-part process must be repeated over and over again, in a potentially endless cycle, for such is the discipline of philosophy, to refine one’s ability to reason continuously.

Needless to say, the discipline required to sustain this ideal of constantly challenging and criticizing one’s worldview is irritating, frustrating, and tiresome. It is as relentless as Fripp’s ongoing, fast guitar lines that never seem to take a rest. Small wonder the symbol for the Discipline album cover is a chain.

Note that the original name that Fripp wanted for this 80s quartet was Discipline, a reaction against his annoyance with The League of Gentlemen, a new wave group he had in 1980. He was sick of “playing with people who are drunk,” and he wanted musicians of top calibre who would have the discipline to play music and focus on the music. Hence, he went from The League of Gentlemen (bassist Sara Lee, organist Barry Andrews, and drummer Kevin Wilkinson) to Discipline (Belew, Levin, and Bruford), who would later be called King Crimson, since ‘Discipline’ doesn’t sound like a fitting name for a rock band, to put it mildly.

Indeed, one must consider the tension felt in trying to maintain the Apollonian ideal of the discipline of the dialectic. Belew’s repeated “it’s only talk” sounds like his exasperation with dealing with such discipline–‘elephant talk’ sounds like a wish to return to an animal’s easy, instinctive way of expressing itself. Such frustrations with philosophically-minded thinking lead us to the next song…

Frame by Frame

These words of Belew’s in the song lyric seem to sum up that tension in measuring up to the Apollonian ideal: “…death by drowning in your own…analysis.” Just as with Belew’s exasperation with “it’s all talk” in the previous song, I suspect that it was Fripp’s endlessly analytical mind that Belew was drowning in. Bruford has made similar comments about how “terrifying” it is to be a member of King Crimson.

On this album, dialectical contradictions are not limited to those of ideas. They also exist in physical, material forms. I don’t generally mean that this ‘dialectical materialism‘ is a Marxist sort. I usually mean that we have conflict and contradiction in the musical structure, in such forms as polymetre.

The first example of this polymetre is in an undulating line of quick sixteenth notes in 6/8 time played by Fripp, while the rest of the band is playing in 4/4. Later, in the 7/8 sections that include Belew and Levin singing, there’s a point where Fripp omits the last of the seven notes in the cycle, beginning on the first note of the repeated cycle when Belew plays its last note before coming back to the beginning himself. A detailed demonstration of how the two guitar lines diverge and conflict with each other can be found here.

Eventually the melodic lines reconverge, symbolically suggesting a sublation of Belew’s ‘thesis,’ if you will, with Fripp’s ‘negation.’ Of course the guitar lines will diverge and reconverge again, a continuation of the never-ending cycle of the dialectic in sonic form.

To go back to the lyric, we analyze something by looking at it in terms of its component parts, slowly–piece by piece, “frame by frame,” like those of a video, “step by step.” In the process of analyzing a thesis, one may “doubt” its validity, this “doubt” giving rise to the negation of the thesis.

Matte Kudasai

The song’s title means “wait, please” in Japanese (待ってください). One envisions, on hearing Belew’s singing, an American woman waiting for the return of her Japanese lover, who calls out to her, “matte kudasai.” She is sad and pining for him, losing patience as she waits, “by the windowpane,” sleeping “in a chair.”

One of the difficult aspects of attaining an Apollonian sense of discipline is having to deal with postponed gratification. Fripp’s bandmates in The League of Gentlemen wanted to drink beer and play music, as I once read of Fripp’s complaining of them, and thus his ending of that band and recruiting Belew, Levin, and Bruford. Fripp wanted a disciplined band, which required an ability to postpone gratification (i.e., beer comes later). One must wait, please.

The American woman thus personifies the act of attaining discipline, and all the sadness that comes from having to postpone gratification, which in turn is personified by her Japanese lover, who is so far away from her, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. For a third time, we sense the difficulty of improving philosophy through the discipline of the Hegelian dialectic.

Musically, the song is essentially a love ballad, with Fripp’s background chord progression reminding us of the one he arranged for “North Star,” a ballad sung by Daryl Hall on Exposure, Fripp’s first solo album. The seagull sounds that Belew makes, supplementing the slide guitar melodies he plays in imitation of his vocal line, suggest the shore of the Pacific Ocean that divides the American woman from her lover in Japan.

I’ve always been partial to the original version of “Matte Kudasai,” which includes guitar leads played by Fripp that have that mellow tone and long sustain, part of his signature sound. These leads are so beautiful that I honestly can’t understand why, since 1989, they’ve been removed from the “definitive” version of the track. The original version has thus been relegated to the status of an “alternative” version.

Indiscipline

The thing about dialectics is that one can’t understand one idea without contemplating its opposite (i.e., a thesis vs. its negation). Hence, to know discipline, as part of the Apollonian, one must also confront indiscipline, as a manifestation of the Dionysian.

The first…striking…thing we notice about this song is Bruford’s wild batterie on the drums. Apart from its virtuosic brilliance, it demonstrates to the full how he enlarged his drum kit for these three albums. He included Simmons SDS-V electronic drum pads, rototoms, octobans, and excluded the hi-hat, at Fripp’s insistence. In these choices for percussion, Fripp was moving King Crimson’s style in the direction of World Music, giving Bruford’s drumming an African feel; and the conspicuous absence of a hi-hat and reduced use of cymbals (which typically would provide a regular punctuating of eighth or sixteenth notes) is conducive to Fripp’s vision of a “gamelan rock” sound, which his and Belew’s guitars would provide in the playing of quick, repeated notes that remind us of those played on the metallophones of a gamelan.

Anyway, the opening of “Indiscipline” gives Bruford an opportunity to show off and improvise, to build up a storm as it were, gradually filling in more and more space with faster and faster playing, going from calm to increasing tension. His use of cross-rhythms against the simple motif (going in layers from a single-note F to its augmented chord) played in 4/4 by Fripp, Belew, and Levin, gives off a dialectic of chaos vs. order that is a musical demonstration of indiscipline, that understanding of discipline in terms of its opposite.

After this…banger…of an opening, the band switches to a 5/4 riff in A minor, while Bruford is hitting beats in eighth-note triplets. Belew plays a lead with variations based on A, C, C-sharp, C-natural.

The music quietens down to that opening motif in F, with Belew doing a spoken-word monologue. What he says was inspired by a letter his then-wife had written him about a painting she’d done. He never explicitly refers to the painting, only saying that he “liked it.”

What it is that he likes, be it a painting or whatever else, is the object of an obsessive desire, the kind of thing that not only distracts one from a sense of discipline, but that also keeps one chained to one’s passions. This is the Dionysian antithesis that will be focused on in my discussion of Beat.

This monomania that Belew is talking about is an example of what the Buddhists would call tanhā, the craving, thirst, or longing that keeps one away from nirvana and its peace of mind. Small wonder that the music gets so chaotic here. Discipline was King Crimson’s least dissonant album (at least as of the 1980s)–which is an unusual feat for the band–since the dominant theme of the album is a sense of order, the Apollonian, requiring much more consonance. It’s fitting, therefore, that the one song that is clearly the dialectical negation of that theme would be a more dissonant one, with Fripp’s screaming guitar phrases heard in the middle of the song.

Belew’s repeating himself when under stress makes me think of Freud‘s notion of the compulsion to repeat, a repetition of traumatic experiences. Note the irrationality of such behaviour, a form of self-harm. It is inherently Dionysian, a linking of tanha (“I like it!”) with dukkha, suffering. Adding to this tension is Fripp’s ongoing hammer-ons and pull-offs of C and A.

In live performances of the song, Belew tended to hold his guitar up, indicating that it was the guitar that he liked, “the more [he] look[ed] at it,” and did think was good. It’s a passion that “remains consistent.” He has also tended to tease audiences with the anticipation of returning from “I did” and “I wish you were here to see it” to the loud, chaotic 5/4 sections, deliberately delaying the transition, a tantalizing of the audience that reinforces the addiction to tanha.

Thela Hun Ginjeet

The title is an anagram of “Heat In the Jungle.” “Heat” refers to firearms or to the police.

The story behind this song is Belew’s recounting of a scary experience he had in the Notting Hill Gate area of London while walking around with a tape recorder. A street gang there accosted him, demanded he play his tape recording, accused him of being a cop, and implied a threat to his life.

Luckily for him, he was let go, but then ran into two policemen who accused him of hiding drugs in his tape recorder. His purpose of going around with the tape recorder, to get inspiration for lyrics for the song, was achieved: he returned to the recording studio and gave his bandmates a distraught account of what had happened out there: Fripp had Belew’s story recorded, and it was incorporated into the song.

The song begins with a guitar line by Fripp, played in 7/8 time, while the rest of the band is playing in 4/4. The resulting polymetre thus reinforces the sense of conflict between the gang’s lawlessness and the cops’ law enforcement…a kind of discipline.

Those rototoms and octobans that we hear Bruford hitting, with the African feel they generate, reinforce that “jungle” aura. Elsewhere, at one point in about the second half of the song, Belew manipulates his guitar feedback in a way that sounds almost like the siren of a police car. Hence, “heat in the jungle” could mean the threat of the street gang or of the cops. Meanwhile, the main riff of the song is anchored by Levin’s bass line of D-sharp hammering on to E, C pulling off to B, then an F-sharp–this last note being the tonic of the key the song is in.

Note that while I say that Apollonian discipline is the dominant theme of this album, this doesn’t mean that there isn’t anything significantly going on in the album to challenge that theme. Discipline is as much about the tension felt in trying to achieve the ideal of discipline as it is about that ideal, as I pointed out, in one form or another, in all of the songs on Side One.

The street gang that harassed Belew personifies that wish to break away from law and order–then the police appear to restore that law and order. This is what discipline is about: attempts to break free of it, as in the chaos of “Indiscipline” and the potential violence of the street gang, then discipline intervenes to punish, as the cops do in their suspicion that Belew had drugs on him.

The dialectic isn’t about one fixed state, its opposite as another fixed state, and their reconciliation as yet a third fixed state. It’s about the fluid movement among these three ephemeral states; hence the shifting away from, then back to, discipline in these songs. We’ll see the same fluidity of theme in Beat and Three of a Perfect Pair.

The Sheltering Sky

This instrumental is inspired by, mainly, the title of the famous novel by Paul Bowles, a writer loosely associated with the Beat Generation, whose writings will be focused on more when I look at Beat. Since this track is an instrumental, and therefore there are no lyrics to allude to anything in the novel, all we have is the title to make a direct reference to it.

Now, the novel is about a married couple, Port and his wife Kit, whose marriage is fraught with difficulties; they leave their American home and go traveling with a friend, Tunner, in North Africa, in the Sahara Desert. Matters get worse for the marriage, as Port enjoys the services of a prostitute one night, and Kit later has a fling with Tunner. Eventually, Port gets sick and dies of typhoid fever. She abandons the body and, Tunner being absent, wanders off in the desert, meets a local man who takes her in as a kind of concubine, dresses her as a boy so his jealous wives won’t know, and they have a brief affair. Held captive by him, though, she eventually escapes, and after wandering around a bit more, becomes disoriented and loses her mind.

As we can see, there’s nothing about discipline going on here. Furthermore, one must wonder: with a story of such existential dread, why is the novel called The Sheltering Sky? Two or three remarks are made here and there in the novel to answer this question, something to the effect of my paraphrasing here: the sheltering sky hides the night and the nothingness behind it; the sky shelters us beneath from the horror that lies above.

Since the sky, or heaven in general, has been used mythologically to represent divine ideals, the spirit (i.e., a sky-father god), as opposed to the crude materiality of life down here on Earth, the world of the flesh and of sin, then we can understand “the sheltering sky” to represent the Apollonian ideal attained through discipline as contrasting dialectically with the Dionysian world of the passions (as is dealt with in Beat). This latter, lower world has been demonstrated in the actions of Port and Kit, their infidelities to each other, and their illnesses, his physical one, and her mental one.

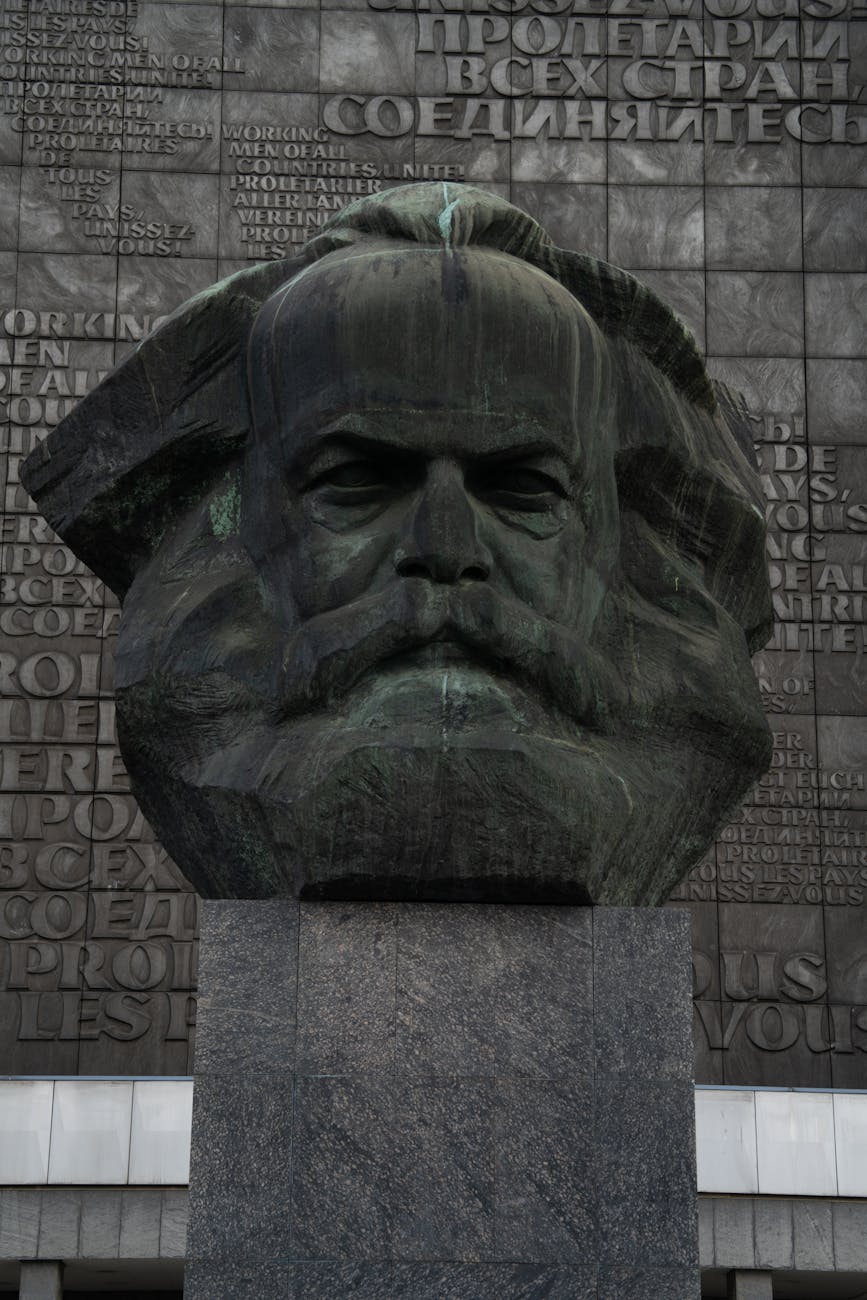

The point is that the Apollonian ideal as attained through discipline shelters us from the reality of our indiscipline, our wild, uncontrollable passions and the mayhem they cause. Recall what it says on the back cover of the album: “Discipline is never an end in itself, only a means to an end.” Religion and other forms of philosophical idealism have always been used to shield us from the painful reality of our material world. The opium of the people is a comfortable illusion that the ruling class uses to sedate us and take away our agency and motivation to make real changes for the better in our world.

The instrumentation for this track reflects the contrast between high tech (Fripp’s and Belew’s use of the Roland GR-300 guitar synthesizer, Levin’s Stick) and traditional instruments (Bruford’s use of the slit drum, which has been played in the folk music of countries in Africa, Austroasia, Austronesia, Mesoamerica, etc.). Furthermore, Fripp’s beautiful leads at the beginning and end of the track, the specific tone he uses, make one think of one of those Arabic reed instruments, such as the mizmar. His leads are played in an exotic scale, adding to the cool, North African effect.

This fusion of modern and traditional musical sources can be heard as symbolic of the materialist dialectic of the wealthy First World when contrasted with the poor Third World. Port and Kit leave the First World of the US and enter the Third World of North Africa, imagining they’ll cure their First World problems (a troubled marriage), when they end up exposed to the dangers of the Third World (Port’s typhoid fever, Kit’s becoming a man’s mere patriarchal property). The sky won’t shelter you from dangers like these.

Discipline

The title track instrumental epitomizes Fripp’s idea of fusing rock with the Indonesian gamelan. It’s also the epitome of the album’s experimentation with polymetre. Fripp’s and Belew’s fast, repeating guitar lines are meant to make us think of those fast, interlocking melodic patterns tapped on the metallophones of a gamelan orchestra.

Fripp and Belew begin with repeating patterns in 5/8 time, though they subdivide differently. Fripp is playing a pattern of 3+2, while Belew is playing one of 2+3. This, of course, isn’t tricky enough for the mighty Crims, so Levin is playing a Stick line in 17/16, a beat Bruford is also doing on the…slit drum?…while he is also hitting a simple bass drum beat in 4/4, to anchor all the music together and provide a groove.

As I said above, these polymetric cross-rhythms symbolize the conflicting aspects of the dialectic, but in a material form (a material form also symbolized in the fusion of traditional music, here in the gamelan, with modern rock instruments, something we just observed in “The Sheltering Sky”). After we hear the opening patterns described in the preceding paragraph, the band shifts to a pattern reminding us of what Fripp was playing in that section of “Elephant Talk” when Belew was making the elephant noises. Associating the first track with this last one reinforces my idea that the dominant theme of the album, and by extension all three albums, is the dialectic, and in the specific case of this instrumental, the Apollonian ideal as attained through discipline.

Later in the track, we hear Fripp and Belew doing fast patterns in 5/16, with polymetric permutations of that, all most redolent of the polyrhythms of the gamelan. At one point, Bruford will hit a crash cymbal to start off each measure of a section in 5/4. This smashing of the cymbal makes one think of a disciplinarian parent spanking the bottom of a naughty child.

Discipline is a means to the end of the Apollonian ideal, the illusion of the sheltering sky, the true dominant theme of the album, but a theme that is often hissed or groaned at, or rebelled against, as in the lawless gang that threatened Belew, or the naughty child getting the spanking. For this reason, it’s fitting that this closing instrumental is a sequel song to “Indiscipline,” the last track on Side One.

III: Beat

Here is a link to the lyrics of the album.

Neal and Jack and Me

This song can be seen as a sequel to the title track instrumental of the previous album, since “Neal and Jack and Me” begins similarly to the way “Discipline” ends. The latter ends with Fripp and Belew playing a repeated three-bar pattern in 5/16 time, after another moment of polymetre; the former begins also with Fripp and Belew playing patterns in 5/8, with some polymetre, too.

Such musical similarities between both tracks, given that they’re from albums with opposing themes, symbolically suggests the dialectical unity of opposites. When Levin (on the Stick) and Bruford come in, with a drum beat in 4/4, Belew starts singing, “I’m wheels, I am moving wheels,” a line from a note Fripp allegedly gave him. The notion of the speaker in the song being a personified “coupe” from 1952 should be remembered, since “Dig Me,” from Side Two of Three of a Perfect Pair, is also about a personified car (a junked one), and thus can be seen as a sequel song to “Neal and Jack and Me.”

The next verse establishes the theme of this album, as manifested through the writings of Jack Kerouac: En route loosely translates On the Road; then we have French translations of The Subterraneans, Visions of Cody (“Cody” being a renaming of Neal Cassady), and Satori in Paris (oddly spelled “Sartori,” as is the case with the instrumental “Sartori in Tangier”). That we are given French translations of the titles of these Kerouac books reminds me of the writer’s fluency in French (though American, Kerouac was of French-Canadian ancestry), as can be seen and heard in this discussion on Canadian TV.

Just as discipline is a means to the end of the Apollonian ideal, the dominant (and scarcely attainable, as a goal) theme of the previous album, so is the agenda of the Beat Generation writers a means to the end of the Dionysian ideal, the dominant theme of Beat. Before, it was about the “talk, talk, talk” of the dialectic, “drowning in your own analysis,” and having to “wait, please” for one’s gratification; now, it’s about being immersed in emotion, rather than repressing it.

The next verses of “Neal and Jack and Me” are all Belew giving us imagery of all the places he might visit and see while going on an imagined car trip through the US with Kerouac and Cassady, or through the streets of Paris. On the Stick, Levin is repeatedly tapping a minor third in the upper register, suggesting the obnoxious beeping of a car horn. Perhaps the impatient people in the car are Neal, Jack, and Adrian. They can’t wait, please.

Of course, all this traveling around the US or France with Neal and Jack is also a metaphor for touring the US and Europe with Robert, Tony, and Bill. Much of the music of this album would have been written during the Discipline tour, and therefore Belew would have been expressing how much he missed home and his wife. The previous album was all about (trying to show) restraint and (attempts at) self-control; Beat is about a release of the full range of emotions, love and yearning in particular…and these emotions lead us to the next song.

Heartbeat

Belew here is demonstrating the pop side of his musical personality. In recording this song, King Crimson did something extraordinary, by their standards: they actually crafted a simple pop love song, playable on the radio. “Heartbeat” demonstrates how thoroughly the musical revolution of punk rock, New Wave, and the resulting 1980s neutered progressive rock. Even King Crimson had to compromise to the dictates of the for-profit music industry. There’s even a video for the song.

The song’s inclusion on the album, though, apart from how pleasant it sounds, is justified in that Heart Beat is also the name of a book written by Carolyn Cassady, Neal’s wife, therefore linking her with the Beat Generation. As I said above, Beat is about emotion (in this case, love), Dionysus, making it the antithesis of the Apollo of Discipline.

I prefer the studio version of “Heartbeat,” when Bruford hits an accent on the second beat during the “I remember the feeing” verses. As for what’s preferable about the live versions, that would be the inventive melodic variations Belew does with his chord progression just before we hear him sing, “I need to feel your heartbeat.” Elsewhere, during Belew’s playing of those chords, there’s Levin’s distinctive playing of four Cs on the bass, as well as Fripp’s lyrical guitar leads.

Sartori in Tangier

Without any alternative explanation for the r, I must assume that the band misspelled satori and didn’t realize their mistake until the album cover was mass produced, and so correcting it would have been too much of a hassle. The title is derived from Kerouac’s Satori in Paris, as quoted in the French in the lyric for “Neal and Jack and Me”…also with that r.

In Japanese Zen Buddhism, satori means “awakening,” “understanding,” and “enlightenment.” Tangier–the International Zone, or Interzone, as William S. Burroughs calls it in Naked Lunch–was, however, a place where a number of the Beat Generation writers went to be open about their bohemian lifestyles, quite the opposite of the spiritual, austere ways of the Buddhists.

Burroughs was attracted to the Zone for its tolerance for drugs and homosexuality, and he went there with the intention to “steep [him]self in vice.” Apart from his having become severely addicted to Eukodol, he also had a sexual relationship with a teenage boy named Kiki. The Zone also tolerated different religions.

I bring all of this up to point out the deeper, dialectical meaning of the expression satori in Tangier. On the one hand, there’s the Dionysian decadence in the Beat Generation writers’ indulgence in drinking, drugs, and free love, including homosexuality. On the other, the Beats were also interested in alternative forms of spirituality, including Buddhism, which Kerouac explored in The Dharma Bums, despite his heavy wine-drinking, too.

A fusion of sin and spirituality is a major theme in Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl,” as I discussed in my analysis of that poem. “Sartori in Tangier” can be understood to be a sequel instrumental to “The Sheltering Sky,” not just because of Fripp’s similarly exotic leads on his guitar synthesizer, with that mizmar effect I discussed above.

Recall that Bowles is loosely associated with the Beat Generation; in fact, Bowles appears in Naked Lunch under the name Andrew Leif, and in the film adaptation, Ian Holm plays a character (Tom Frost) based on Bowles, during the Interzone section of the movie. Furthermore, Kerouac, Ginsberg, and of course Burroughs are represented by characters played by, respectively, Nicholas Campbell, Michael Zelniker, and Peter Weller in the movie (even Kiki was represented, with the same name, by Joseph Scorsiani). This fictionalized representation of Beat Generation writers was also adopted by Kerouac in his novels (recall “Cody” for Cassady).

So while “Sartori in Tangier” represents that dialectical fusion of Apollonian self-control leading to Buddhist enlightenment, on the one hand, with Dionysian indulgence in vice and pleasure, on the other, so does “The Sheltering Sky” represent such a fusion, with the sky as a supposedly heavenly shelter against evil, such as the dangers Port and Kit are exposed to, and their sins of infidelity. Hence, “Sartori” is a sequel to “Sky.”

Just as I said about Discipline with respect to the dialectic, it isn’t about that album being 100% thesis, this second album being 100% negation, and third being 100% sublation. The dialectic describes a fluid interplay of these three elements, not each given in a state of perfect fixity. So just as Discipline has its “Indiscipline” and lawless gang in “Thela Hun Ginjeet,” so does otherwise Dionysian Beat have its satori, or attempt to achieve spiritual enlightenment through the discipline of Apollo.

The instrumental opens with Levin playing a solo on the Stick. It’s played in free time, with a volume pedal, in D. Then he starts playing a distinctive, tight rhythm with low D notes and high ones in G and A, and variations thereof. Bruford comes in on the drums, and in the studio version, you can hear Fripp playing a simple tune on an organ. He soon comes in with those exotic, mizmar-like leads on the guitar synthesizer that I discussed above. In live versions of the instrumental, such as this one, Belew is a second drummer.

Waiting Man

This song can be seen as a sequel to “Matte Kudasai,” which you’ll recall means “wait, please” in Japanese. This song also seems to reflect how Belew, on tour, was missing his wife and home life, him aching to get back there.

Live versions of the song had Belew and Bruford doing a duet on tuned electronic drums, which the Beat tribute to the 1980s King Crimson also did, but with Belew and Tool drummer Danny Carey replacing Bruford. Levin joins their melodies by tapping notes of B, two in F-sharp, three in G, and one again in F-sharp. This is all played in 3/4 time, and in D major. Fripp is playing repeated notes in D octaves. It has a kind of Latin American feel rhythmically.

Belew sings about coming home, about the gratification of his waiting being finally over. This is in contrast to the postponed gratification of “Matte Kudasai.” In this way, we can see how “Waiting Man” is the dialectical antithesis of “Matte Kudasai,” in which the seemingly endless postponement of gratification causes great sadness. Here, the “tears of a waiting man” are tears of joy, with the “smile of a waiting man.”

As I said above, Discipline is about the restraining of emotion, whereas Beat is about the free expression of emotion, the dialectical antithesis. In the song, has Beleew really achieved the gratification being “home soon, soon, soon,” or is it just wish-fulfillment, a reverie he’s having about being home with his wife while actually being still on tour with Fripp, Levin, and Bruford? It doesn’t ultimately matter, because this song, like most of the music and lyrics of Beat, is about the free expression of desire, as opposed to Discipline‘s Apollonian self-control and restraint.

The waiting is still there, in any case, with all the pain that goes along with that waiting, so in the middle of the song, there’s a key change to G-sharp, a tritone away from D (the diabolus in musica), with some fast arpeggio picking by Fripp on the high frets of the guitar. Then there’s a shift to A, with some dissonant guitar howling by Belew, to express the pain from his waiting.

The fact that the key of A is the dominant for D means that, apart from Belew’s dissonant guitar howling, the musical tension (dramatizing the waiting man’s growing impatience to get back home) is at its greatest intensity, even if a leading tone–C-sharp–isn’t immediately apparent in the music at this moment. So when we come back to the tonic key of D major, we feel great relief.

And indeed, when we’re back there, back at home in D major, there’s the greatest happiness in Belew’s lead vocal and Levin’s back-up vocal, both of them moving in thirds: “I return, face is smiling…feel no fret…”

Neurotica

The song’s title is derived from that of a Beat-era magazine. Apart from this reference, the title has other overtones of meaning. Neurotic has been used by psychoanalysts to describe how an analysand has emotional problems caused by unconscious psychic conflicts. Such a notion is useful in developing the album’s themes of a whirlwind of emotion, its libido, its intensity, its wildness, and the battle to keep it under control. The title is also a pun on erotica; I’ll get to the implications of that later.

The studio version of “Neurotica” begins with a simple organ part played by Fripp, one taken from “Häaden Two,” from Side Two of Exposure. Then the band comes in with an explosion of activity: Belew makes a siren-like sound on his guitar, Fripp plays chords in 5/8, Bruford is pounding away chaotically, and Levin plays dark notes in the lower register of the Stick.

We get an atmosphere of a busy city downtown–car horns beeping and everything hectic. Belew’s spoken-word verses describe a surreal world of wild animals inhabiting the city: cheetahs, a “hippo…crossing the street,” “herds of young impala,” a gibbon, a Japanese macaque, and a “hammerhead hand in hand with the mandrill.”

In the second verse, a reference is made to the third track on Side Two, “The Howler” (see below), which is in turn a reference to Ginsberg’s poem, “Howl” (see above for a link to my analysis of the poem). It is fitting thus to associate “Howl,” however indirectly, with all of these references to wild animals–which continues in this verse: “the tropical warbler,” the ibis, the snapper, “the fruit bat and purple queen fish”–since the Dionysian wildness of “Howl” can easily be symbolized by all these wild animals.

Further cementing the association of this zoo-city with Beat Generation writers like Ginsberg is, during these spoken-word verses, Levin and Bruford playing in a jazz style, with a walking bass line on the Stick and a swing rhythm on the drums. The Beat writers often wrote of their partying to jazz.

In the middle of the song, the musical chaos representing this surreal zoo of a city is replaced with a calmer section of that 80s Crimson staple of repeated guitar lines in 7/8 time. In this middle section, Belew sings a three-line verse twice, the second time with a harmony vocal by Levin. The speaker’s arriving in Neurotica reminds me of Burroughs’s entering Interzone (as William Lee) in Naked Lunch, or of Port and Kit coming to North Africa in Bowles’s novel. The “neon heat disease” reminds me of the typhoid fever Port dies of, and it also seems to represent the fiery passions of the Dionysian lifestyle that Beat is all about.

Belew’s “swear[ing] at the swarming herds” seems to refer to all the profanity you’ll find in the books of the Beat Generation, much of which raised the eyebrows of readers back in the 1950s in a way that it wouldn’t today, given such things as the obscenity trials that Ginsberg was put through for “Howl,” and Burroughs for Naked Lunch. The “swarming herds” are of course the animals of Neurotica, which represent not just the North African locals in general, from the point of view of First World tourists like Bowles and Burroughs, but also specifically the people those tourists would have used for their sexual release.

“I have no fin, no wing, no stinger,…” etc. sounds like one of those tourists being symbolically emasculated by a venereal disease caught from one of the local catamites, people like Burroughs’s Kiki. And with neither a claw nor camouflage, the tourist has no protection from the dangers of the North African desert, as did hapless Port and Kit.

With a return to the noisy, chaotic cityscape of the beginning of the song, Belew’s spoken-word third verse lists off a number of other wild animals. His reference to “random animal parts now playing nightly right here in Neurotica” once again suggests the…parts…of local prostitutes enjoyed by the tourists in North Africa (note in particular the “suckers“). The song ends with Fripp playing leads on his guitar synthesizer like those heard on “The Sheltering Sky,” reinforcing the feeling that we’re in an area where Bowles’s Port and Kit once were, and where Burroughs met Kiki.

Two Hands

With this song, we move back to the territory of “Heartbeat,” except now the ballad isn’t merely about aching to be with one’s beloved. There’s an element of jealousy here. As I’ve said above, Beat is about the full expression of emotions; instead of the lust of “Neurotica” and its dangers, now we must beware of the green-ey’d monster.

The lyric describes a surreal scene of a painting with human consciousness hanging on a bedroom wall watching two lovers who are at it in bed. The face in the painting would “pose and shudder,” but it cannot do anything to stop the man from having the painting’s woman…or at least I assume the sexes here are as such, with Belew’s voice singing about the painting’s pain.

Included in the beautifully plaintive music is Bruford’s playing of the slit drum, again reminding us of “The Sheltering Sky.” Are the man and woman who are making love Tunner and Kit, or is it her with the local who’s using her as his concubine? Is it Port with the prostitute, and Kit is watching?

The lyric to this song was written by Belew’s then-wife, Margaret, so she of course would have had her own personal meaning for it: is she the face In the painting, fearing that her husband is enjoying the charms of a groupie while on tour? Such an interpretation would justify the comparison with Port and the prostitute in Bowles’s novel. In any case, the jealousy expressed fits in with the themes of the album.

After Fripp plays a beautiful solo on his guitar synthesizer, Belew comes back in singing about the wind blowing the hair of the watcher in the painting in the direction of the two lovers, but “there are no window in the painting…no open windows…” The jealous watcher is being tormented in two ways: he or she is being pushed, as it were, by the wind…if only by the hair…closer to the lovers; an open window would be the only way for the wind to come in and push him or her closer, yet the lack of windows implies nowhere to escape. The watcher must stay and watch, and move only closer, with bent hair implying a mind bent by the pain of having to watch.

After a refrain of the first verse, the song ends as it began: with guitars playing in C and in 6/8, as opposed to the 4/4 time of the rest of the song.

The Howler

This song makes allusions to Ginsberg’s poem, “Howl.”

The studio version begins with a fade-in of guitars in G minor and in 7/8, with Bruford doing some kind of African-style drumming. Next comes the main riff, which is played on Levin’s Stick in D minor and in 5/4, and is backed up on Fripp’s guitar synthesizer.

When Belew sings of “the angel of the world’s desire,” I’m reminded of what I wrote in my analysis of “Howl,” in which I discussed, similar to what I’ve been saying here about the dialectical relationship between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, a unified relationship between heaven and hell, sin and sainthood, nirvana and samsara, and if you will, angels and worldly desires.

The speaker is “placed on trial,” just as Ginsberg was for “Howl,” and Burroughs was for Naked Lunch, in both cases because they were accused of obscenity. Belew’s singing makes references to cigarettes–and in the second verse, to matches–as sources of fire. The cigarette could be a marijuana or hashish joint, and thus in turn be an indirect reference to the drug use of the Beat Generation writers; that “howling fire” or “howling ire” could also symbolize the Dionysian frenzy of the Beats.

We come back to the 7/8 passage in G minor, then the D minor music with the 5/4 Stick riff returns, and then the second verse. Paralleling the angel of the first verse, Belew now sings of “the sacred face of rendezvous.” I suspect that the rendezvous is of either fellow drinkers/drug users or illicit lovers, gay or straight, as are described in Ginsberg’s poem; if so, then this opening line further parallels the first verse’s opening line’s “angel of the world’s desire.” These lines reinforce the theme of a fusion of heaven and hell, of sinner and saint.

This meeting of Bohemians happens “in subway sour.” Ginsberg’s poem makes a number of references to being on subways: for example, in the first part, where it says that he and his Dionysian friends “chained themselves to subways for the endless ride from Battery to holy Bronx on benzedrine”. The subway ride is a drug trip, a sweet yet sour one.

Their “grand delusions prey like intellect on lunatic minds”–yet another fusion of Apollonian rationality with Dionysian craziness. This line also reminds us of the famous opening of Ginsberg’s poem: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,…”

While Belew is singing (soon with a harmony vocal by Levin a third away) of not wanting to burn, that is, not wanting to endure the suffering (dukkha) of burning that inevitably follows from the fire of Dionysian desire (tanha)–recall my discussion of these Buddhist concepts in the “Indiscipline” section above–we’re hearing parallel E and F minor 7th chords on the guitar. The music here is playing in alternating bars of 8/8 and 7/8, with the eighth beat of the first of these pairs being a syncopation, a stressed off-beat to confuse the listener momentarily as to which bar is of the eight eighth notes, and which the seven of them, of the pairs of bars. After all, these four guys are the mighty Crims, and they’re very tricky.

After this section, we go back to the D minor music with Levin’s 5/4 Stick riff, and Belew does more dissonant guitar howling, a musical representation of that “howling fire,” in turn representing the Dionysian self-destruction described in much of Ginsberg’s poem. The song ends with the original 7/8 music in G minor, fading out as it faded in at the beginning.

Requiem

As the title of this instrumental improvisation implies, the emotion given full expression here is sadness. There was good reason for this sadness, since during the recording of this track, tension was building between Belew and Fripp. When the group got together, Belew got mad at Fripp for a number of reasons: recording in the UK, there was his sadness from being far from his American home; he was vying with Fripp for attention in their guitar work for the track; and Belew was being pressured to come up with some lyrics and melodic material for it, too. So Belew, in his frustration, told Fripp to leave the studio.

Visibly upset, Fripp left and went to his home in Wimborne Minster. He was’t heard from in several days, worrying everyone and leaving Belew and producer Rhett Davies to mix the rest of the tracks without Fripp. The group didn’t get back together until the Beat tour began, Belew having apologized to Fripp.

“Requiem” is built on Frippertronics, a tape-looping technique Fripp derived from his collaborations with Brian Eno back in 1972-73, when they recorded and released their first album together, (No Pussyfooting). Frippertronics is an analogue delay system using two side-by-side reel-to-reel tape recorders; the tape travels from the supply reel of the first machine to the take-up reel of the second, thus what’s recorded on the first is played back on the second. The second machine’s audio is then routed back to the first, causing the delayed signal to repeat while new audio is mixed in with it.

Using Frippertronics, Fripp would layer recordings of guitar lines one on top of the other in real time, lines of sustained, harmonized guitar notes that would end up sounding out sustained chords. This is what we hear at the beginning of “Requiem.” On top of these tape loops of guitar leads, Fripp solos in that sustained tone that is one of his guitar staples.

By the middle of the instrumental, not only have Levin and Bruford entered, the latter bashing about on his drum kit chaotically in free time, but Belew also comes in with more of his dissonant guitar howling (I’m reminded of Cecil Taylor Unit improvisations). One might connect this guitar howling here with that of “The Howler” and “Waiting Man.” Belew’s pain and sadness–from being far from his American home, his “sad America,” and his wish to be there soon and cry on Margaret’s shoulder–are being likened to not wishing to burn in Ginsberg’s Dionysian destruction. Similarly, Bruford’s chaotic drum-bashing here, as also in “Indiscipline” and “Neurotica,” links up Beat‘s theme of being the antithesis of the album’s Apollonian predecessor.

IV: Three of a Perfect Pair

Here is a link to the lyrics of the album.

Three of a Perfect Pair

Now, as I’ve said above, this third album’s main theme is the sublation of the contradictory relationship between the themes of the previous two albums…or really, just sublation in general. What must be understood about the Hegelian sublation, however, is that it doesn’t end the story, especially not with a peaceful, happy ending. On the contrary: the sublation only becomes a new thesis to be opposed and sublated again. This process of thesis, negation, and sublation goes on again and again in an endless cycle.

It’s as though a permanent state of conflict and contradiction is the real ideal, and not the sublation’s attempt at a reconciliation or resolution. Hence, the “pair” is already “perfect” as it is, while Element Number “Three” is, if anything, a kind of monkey wrench thrown in there to mess everything up, which would explain the paradoxical name of the album and title track. As with Discipline and Beat, this third album’s dominant theme (of sublation) is not to be understood as being in a state of permanent fixity.

Recall how I mentioned, in the introduction above, that the two blue arches on the front cover of this third album are phallic and yonic symbols, representing the male and female principles. The lyric to the title track is about a he and a she, opposite sexes personifying dialectical opposites, while they personifies the dialectical synthesis or sublation.

She, the thesis, is susceptible to any critique from the negation, who is impossible for the thesis not to have to face (and with his unattainably high standards, he’s also impossible to put up with). The burden they share, like Christ carrying His cross, is working out a reconciliation of their differences, the sublation.

The irony of this disharmony, as described in the lyric, is heard in the music, with Fripp’s and Belew’s guitars playing harmonious lines, thirds apart, in 6/8 time, those repeated guitar lines that remind us of that gamelan sound they were working on in Discipline. Similarly, Belew and Levin are singing these verses in parallel thirds, in…perfect…harmony. Thus, the juxtaposition of the disharmony of the man’s and woman’s relationship with the harmony in the music is a sublation.

While the first verse dealt with conflicts between two people, the second one is about internal conflict within the man and within the woman. With him, it’s “his contradicting views”; with her, it’s “her cyclothymic moods.” Cyclothymia is essentially a form of bipolar disorder, with alternating periods of elation and depression, cyclical ups and downs, but they aren’t as severe as those of regular bipolar disorder. The point is that these ups and downs are another manifestation of juxtaposed dialectical contradictions. The “study in despair” is in how the contradictions are never permanently, decisively reconciled. Sublations are brief, leading to new oppositions, hence there’s no hope for a permanent resolution. It’s a “study in despair” in that one dies “by drowning in your own analysis.”

It’s interesting how these two verses are set to music that uses the 12-bar blues progression, though without any of the blue notes. I’ve mentioned, in my analyses of the first two Crimson albums, how the 12-bar blues chord progression is sometimes presented, but in a perverse fashion, as it is here. However you hear it, dialectical contradiction gives you the blues.

With the move to “too many schizophrenic tendencies” is a move to 7/8, a fittingly asymmetrical time signature, as well as Belew and Levin singing separately, the former singing the bridge verse and the latter echoing the words “complicated” and “aggravated.” Instead of the voices singing together, cooperating in…perfect…harmony, their separateness suggests alienation. The “perfect mess” is a sublation of heaven and hell.

Three bars in 4/4 time, again with that gamelan guitar sound, lead into a repeat of the second verse. Then there’s a repeat of the bridge verse in 7/8. That gamelan guitar sound comes back, but in 6/8 this time; then there’s another 7/8 section, essentially in F-sharp and with a “schizophrenic” solo by Belew, an example of his innovative use of unconventional guitar sounds. Note that schizophrenic is derived from Greek words meaning a “splitting” of the “mind.” Such a split suggests dialectical contradictions, once again.

A singing of the bridge verse two times, and a repeat of the 4/4 time guitar line, ends the song.

Model Man

I’d say the speaker in this song is the man from the title track, just as the woman sung of in “Man With an Open Heart” is the same woman, too. He suffers from the difficulties of his relationship with her, a dramatization of the dialectic and its eternal cycle of conflicts (“calm before the storm”). The pain of his suffering is in the signs, the symptoms, the strain, and “tension in [his] head.”

While the main riff, in A major, is in 4/4, the chorus is in 7/8, the cutting off of a final eighth note suggesting an incompleteness, an imperfection. We hear sublations of perfection and imperfection in the words “”imperfect in a word, make no mistake”; similarly, though he’s “not a model man,” he’ll “give you everything [he has].”

I suspect he’s singing these words to the woman from the title track and in “Man With an Open Heart.” Is he the man with the open heart, who “comes right now,” or is he projecting his lofty standards of unrealistic perfection onto her? Is he “sleepless at night” because of his demands on her? Speaking of which,…

Sleepless

The song opens with a great slapping bass line by Levin, crisp, sharp, and precise. When Bruford, Belew, and Fripp join in, the two guitarists make some atmospheric sounds on their guitars as they play call-and-response chords.

Sleeplessness itself is a sublation, if you will, of sleeping and wakefulness. This is demonstrated in Belew’s lyric when he sings, “In the dream…” and “You wake up in your bed.”

He’s in “the sleepless sea” of his dream, which sounds like the formless chasm of the unconscious, realm of the Shadow and all such unpleasant, repressed thoughts, a land of nightmares. Now wonder he can’t sleep.

The imagery in this lyric, about the sea and all that’s associated with it–“the distant reef,” “emotional waves,” submarines, and the beach–is apt, given how those waves can be seen to symbolize the fluid movement of sublation back and forth between theses (crests) and negations (troughs). The back and forth arguing of the dialectic, like those call-and-response chords on Fripp’s and Belew’s guitars, is relentless and never-ending. No wonder he can’t sleep.

The speaker tries to reassure himself: “It’s alright.” He tries to relax: “And don’t fight it.” But needing to reassure himself that it’s alright is a negation of the reality that it’s very much not alright. His telling himself not to fight it is himself very much fighting it. He wouldn’t tell himself not to fight it if he didn’t need to. It’s not alright to feel a little fear, especially when you need to get some sleep. The dialectical opposite of what he’s saying to himself is the truth.

The “silhouettes” of “shivering ancient feelings” are old memories, the shadows and traces of pain from long ago. These painful memories cover his floors and walls, which are “foreign,” alien to him, yet being of his own home, symbolic of parts of his mind, they should be intimate to him. Again, being alienated from one’s very self is a sublation of intimate vs foreign.

The submarines that go about in the formless sea of his unconsciousness are the personal demons of his Shadow, his “foggy ceiling,” that part of his home, his mind, which he should be well acquainted with, but which is a mystery to him. If these repressed feelings aren’t brought to consciousness, they’ll keep him sleepless at night.

In the second singing of the chorus, we can hear Fripp and Belew in the background playing those trademark guitar lines in in which I suspect there’s more polymetre, symbolizing conflicting thoughts in the speaker’s mind. (Note that I am analyzing the original version of the song we got from the old vinyl recording of 1984.)

There’s one bar of 3/4 after this second chorus, then we hear Belew’s guitar solo. In the original version, you also hear the thumb-thumping on every beat in Levin’s slapping bass line, with no breaks in between thumps, as in the later version of the song.

“The figures on the beach in the searing night” sound like all those homunculi in speaker’s mind, be they the Jungian archetypes, or the Kleinian internal objects, or both. These are the conflicting voices in the battleground of the speaker’s mind: they are why he can’t sleep.

The song ends with more of the call-and-response chords of Fripp and Belew, and with Bruford’s African rattling of the rototoms, ’til the song fades out.

Man With an Open Heart

This song, I’d say, is a sequel to “Model Man,” for it mirrors and dialectically opposes the themes of the previous one. In “Model Man,” there’s all of the man’s sickness and anxiety over not being able to measure up to a stratospheric standard of perfection. In this song, instead of the woman being worried about such lofty ideals, she’s liberated from the need to live up to them. She can be her idiosyncratic self, and she doesn’t care if anyone disapproves of her.

As a bird, she can have both wings to fly freely. In this line, as well as in the two lines that follow, she shows that she’d exemplify the feminist idea of the liberated woman: not having to answer the phone, like the feminine stereotype of the receptionist or secretary; “in the comfort of another bed,” she wouldn’t feel restricted to sex with a husband.

Now, “a man with an open heart,” that is, a man who is open-minded enough to accept the ways of such a woman, demonstrates the opposite attitude of those who demand a Jesus ideal for “a model man,…a saviour or a saint.” An open-hearted man wouldn’t care if the woman doesn’t measure up to the lofty ideal of the Virgin Mary.

This man with an open heart is coming here right now. Who is he? Is he the speaker in the song? I have my doubts, since the speaker sings of him in the third person: “here comes right now.” He doesn’t say, “Here I come_ right now.” He doesn’t even say, ‘here he comes right now,’ as if he’s so jealous that he wishes he could eradicate the man with the open heart by omitting the pronoun that would refer to him. The moaned melody after this line suggests the speaker is groaning out his jealousy.

The harmonic progression of the verses includes a D major seventh chord, a D minor seventh chord, and an A major chord with an added 9th (or is it an added 6th? or is it a 6/9 chord?). These are heard three times, then with the thrice-sung “man with an open heart” line, we have chords of C-sharp minor and G-sharp minor; “here comes right now” is backed with a B minor chord, and the moaning is with an E minor chord.

In the next verse, Belew sings of how the liberated woman could behave in a number of seemingly erratic ways, being moody, dramatic, evasive, or “irregular and singing in her underwear,” all behaviours that a conservative society would disapprove of in a woman. A man with an open heart, though, would not be at all troubled with such behaviour in her.

Now, “wise and womanly introspectiveness” is of course a virtue in itself, but those who would reinforce sex roles don’t want that. “Her faults and files of foolishness” won’t measure up to the high standards of a ‘model woman,’ but a man with an open heart won’t mind. As we can see, this song is the dialectical opposite of the one in which he is worried about being pressured into perfection. “She is susceptible” to fault and criticism, and “he is impossible” to please.

Nuages (That Which Passes, Passes Like Clouds)

Nuage is ‘cloud’ in French. The passing movement of clouds in the sky, a shift from one position to another, seems symbolic of becoming, which for Hegel in his Science of Logic is the sublation of being vs nothing (Hegel, pages 82-83): “Pure being and pure nothing are…the same. What is the truth is neither being nor nothing, but that being–does not pass over but has passed over–into nothing, and nothing into being. But it is equally true that they are not undistinguished from each other, that, on the contrary, they are not the same, that they are absolutely distinct, and yet that they are unseparated and inseparable and that each immediately vanishes in its opposite. Their truth is, therefore, this movement of the immediate vanishing of the one in the other: becoming, a movement in which both are distinguished, but by a difference which has equally immediately resolved itself.”

The passing of being into nothing and nothing into being is here symbolized by the passing clouds. The clouds represent being, the cloudless air represents nothingness, and the passing of the clouds represents becoming…sublation.

Because clouds are in the sky, and this instrumental has a vaguely Middle Eastern feel, it can be deemed a sequel to “The Sheltering Sky” and “Sartori in Tangier.” Since the first of these three is thematically, as I explained above, about the relationship between, on the one hand, the Apollonian, celestial ideal as an illusory protection against, on the other, the horrors of our self-destructive, Dionysian reality here on Earth, and the second instrumental is paradoxically about spiritual enlightenment in a place where the Beat writers indulged in vice, then “Nuages” can also be seen as a sublation of the Apollonian and the Dionysian in North Africa.

The music begins with Bruford playing beats on his electronic drum kit, which is programmed to make unusual sounds that I can describe only as making me think of sticking one’s feet in puddles. Fripp comes in with the guitar synthesizer, which has been programmed to remove the plucking attack of his plectrum on the strings, as one would hear with a volume pedal. The effect is an ethereal one making pictures in one’s mind of clouds passing in the sky. He’ll use a similar effect with his Roland GR-300 on the album’s next track, “Industry.”

Next, Fripp overdubs guitar leads with that sustained tone he’s many times gotten from his black Les Paul Custom. Belew does a brief solo in the middle of the track, and we return to Fripp doing his leads until the piece ends as it began, with Bruford’s electronic drums.

And this is the end of Side One of the LP, or as it’s called on the LP, the Left Side–Side Two thus of course being the Right Side. Such a naming of the sides is apt given their dialectically opposing natures.

Indeed, Fripp himself summed up the nature of the musical content well. He said Three of a Perfect Pair “presents two distinct sides of the band’s personality, which has caused at least as much confusion for the group as it has the public and the industry. The left side is accessible, the right side excessive.”

As I said at the beginning of this analysis of Three of a Perfect Pair, the theme of sublation that we get on the left side becomes a new thesis to be negated, as is expected of the Hegelian dialectic. In this case, to paraphrase what Fripp mentioned in the above quote, the music of the left side is largely radio-friendly (I recall when the album came out, and the title track and “Sleepless” were being played on the radio); the music on the right side, however, is mostly instrumental and mostly of an experimental nature, with lots of King Crimson doing their trademark deliberate dissonance.

Indeed, the whole reason that King Crimson remained a cult band without ever enjoying substantial mainstream commercial success is because, as a music magazine article I once read about GTR, their music requires too much intelligence to appreciate. One of the Toronto DJs, who was playing tracks like “Sleepless” back in 1984, said in all bluntness that he didn’t like playing King Crimson’s music because he thought it was “too brainy.” As a fan of the mighty Crims, I find such descriptions of their music quite flattering.

Industry

This instrumental seems to be a musical description of the growth of industry, from its beginnings in the Industrial Revolution of late 18th century England to the fully industrialized world of today. Linked with the advances in technology and the use of machinery (as expressed in the music through Fripp’s and Belew’s guitar synthesizers, Bruford’s electronic drums, and Levin’s tapping of the bass C note on a keyboard synth, as well as Belew’s machine-like guitar rumblings and Bruford’s machine-like precision on the drums) is also the growth of capitalism.

These historic developments, so bad for the environment and for the working class, explain why the tone of the music is so dark. And since in the second part of Ginsberg’s “Howl” we see what is the cause of the madness of “the best minds of [his] generation”, namely, Moloch, who personifies alienating industrial capitalism (see my analysis of “Howl”), we can see “Industry” as a sequel to “The Howler.” Recall such moments in the second part of “Howl” as these to see my point: “Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money!…Moloch whose factories dream and croak in the fog! Moloch whose smoke-stacks and antennae crown the cities!”

Now our discussion of the dialectic must go from Hegelian idealism to Marxist materialism. I’ve already mentioned how the sublation of any thesis and negation must become a new thesis to be negated and sublated again. This three-part process repeats itself over and over again in a potentially endless cycle. In the case of historical materialism, we see this process begin in the ancient world in the form of the master (thesis) vs the slave (negation). These are sublated into a new thesis and a new negation, respectively the feudal lord and serf. With such events as the French Revolution, the contradiction of feudal lords and serfs is sublated into our modern contradiction, the bourgeoisie (thesis) and the proletariat (negation), which Marxist thinkers see being sublated through socialist revolution.

So when we see the conflict between the he and she of the title track, we’re seeing a personified dramatization of the previous contradictions of history. Their being thrown together suggests a sublation that will become the basis for the new thesis, 19th century industrial capitalism (musically expressed in this instrumental, of course), which will be negated by the proletariat in the form of revolutionary resistance.

These contradictions are seen in the illusory idealizing of “the sheltering sky,” or Apollonian heaven, the opiate God protecting us from sin, as well as in the “model man…a saviour…a saint,” as opposed to the lowliness of life on Earth, the Dionysian, “her faults and files of foolishness.” In the past, there was the divine right of kings and the sexist assumption of men’s ‘superiority’ over women. These past contradictions have been sublated into modern capitalism and ‘girl-bosses,’ as well as diversity in management. The contradiction of bourgeois and proletarian remains, though. I’ll go more into the evils of contemporary neoliberalism later. Now let’s look at the music.

The instrumental begins with, as I said above, Levin playing a low C note on a keyboard synth, with Bruford backing him by softly tapping on his snare drum. It’s two eighth notes, a quarter note, and two quarter rests, so we begin with two bars of 4/4. Then it’s four eighth notes, and the rest is the same as in the first two bars, so now it’s a bar of 5/4. Then the 4/4 and 5/4 alternate throughout the rest of the track, though Levin will, on the 5/4 bars, sometimes make the second of the four eighth notes a G-sharp, or a minor sixth above the Cs.

Fripp comes in with the guitar synthesizer, playing those ethereal chords without the sound of plucking–as in “Nuages”–the tones fading in. Belew plays lyrical leads on top of Fripp’s chords, playing glissandi on what must be a fretless guitar. Though Levin’s synth Cs and Bruford’s snare sound mechanistic, so far the music is generally pleasant, symbolically suggesting the promising future of a raised standard of living that comes with industrialization.

Levin adds some slapping bass, with G and G-sharp, then these notes with C-sharp and C, or these latter two and another G-sharp, or variations thereon. Bruford also comes in bashing with crackling precision. The addition of these instruments suggests the growth of industry and the development of better technology.

Next, Fripp’s guitar synthesizer comes in with a new sound: low, dark tones (C, G, G-sharp, then these with G, G-flat, etc.) on which he’ll layer parallel ones–two, then three, then more. In live versions, Belew added an upper guitar lead to intensify the dramatic effect of this ominous development.

This parallel layering of a chromatic melodic line symbolically suggests the growth of industrial capitalism, and refinements in technology for that purpose. To gain an advantage, however temporary, over the competition, a company will invest in better technology, better machines, in order to cut labour costs and bring prices down, because value is determined by the socially necessary labour put into making a product. Soon enough, though, the competition will adopt the same new technology and machinery, thus reducing their costs and prices, and overall the rate of profit will tend to fall over time, a tendency that Marx predicted would eventually lead to the destruction of capitalism by its own contradictions.

The ugliness of these developments, that is, the oppression of the working class via wage slavery, the degradation of the environment, and the globalization of imperialism, is expressed in “Industry” through the angular guitar growling of Belew and Fripp. The former’s guitar makes us think of the grinding of machinery, and the latter’s trademark screaming phrases suggest the cries of suffering humanity.

Towards the end of the instrumental, the music quietens down, finally ending as it began, with the low Cs on the synth and Bruford’s snare drum.

Dig Me

The only song on The Right Side with vocals begins immediately after “Industry” ends, suggesting a continuity between the two tracks. Such a continuity is perfectly valid, since the problem of pollution as expressed in this track is of course a direct result of industrialization.

In a live performance of both “Industry” and “Dig Me,” back to back in Montreal in 1984, Belew addressed the audience by asking them, in between the performance of the two pieces, if they wanted “some more of the weird stuff.” The audience cheered for it enthusiastically, but of course most listeners would be alienated by such avant-garde music. Alienation, nonetheless, is the whole point, given the themes dealt with in this music.

The song begins with more of Belew’s metallic, machine-like guitar rumblings, and these, combined with his scratching, dissonant rhythm guitar chords, are a fitting musical complement to the lyric, which is a surreal monologue given by a junked, rusty car in a junkyard, but the car has human consciousness.

I see this song as a sequel to “Neal and Jack and Me,” in which, recall, the speaker is “moving wheels…a 1952 Studebaker/Starlight coupe.” We thus note here a sad decline from the wild and carefree days of going on the road with Cassady and Kerouac to languishing as a wretched car among other totaled automobiles and metallic garbage.

This decline can be seen as allegorical of how the West has gone from the post-WWII economic prosperity to, as of the writing and recording of “Dig Me,” the beginnings of Reaganite/Thatcherite neoliberalism, something that since those ominous beginnings has in turn continued its steady decline into the 21st century schizoid world we live in today. Indeed, the Right Side of Three of a Perfect Pair is, in my opinion at least, as prophetic a set of music as In the Court of the Crimson King is.

When Belew’s alliterative, spoken-word monologue complains of how “the acid rain floods [the car’s] floorboard,” etc., and the car lies “in decay, by the dirty angry bay,” we’re reminded of how industrial capitalism has resulted in environmental degradation.

Now, the opposition between the radio-friendly accessibility of the Left Side vs the experimentation of the Right Side isn’t any more absolute than is the Apollonian in Discipline or the Dionysian in Beat. Like the white dot in yin and the black dot in yang, there are brief moments of simpler music on the Right Side as well as briefly progressive moments on the Left Side (e.g., the 7/8 passages).

The chorus of “Dig Me” is an example of something more human and relatable for the listener among the otherwise “weird stuff” on the Right Side. As I’ve said a number of times already, the three phases of the dialectic aren’t in a state of permanent fixity: they’re just there to simplify our understanding of the actual fluidity of the dialectic.

The spoken-word verses emphasize the mechanical aspects of the ‘car-man.’ The chorus emphasizes the human aspects. Accordingly, Belew sings with a harmony vocal from Levin, and we hear a straight-forward guitar melody of G major added second, then B, C, and E, Levin backing it up on the bass, with Bruford playing a simple 4/4 beat. This simplicity contrasts with the chaos of the dissonant chords and free rhythm drum bashing of the distorted spoken word verses.

As Belew and Levin are singing about wanting “to ride away” and not wanting to “die in here,” we can empathize with the car-man, for today, we too “wanna be out of here,” out of this ecocidal, neoliberal dystopia, in which high technology is increasingly taking us over.

That the car-man has metallic skin reinforces his half-man, half-machine nature, symbolic of how so many of us today feel alienated from our species-essence as a result of living in the high-tech capitalist world, one that reduces human beings to mere commodities who must sell our labour in order to survive. The car-man’s skin is “no longer an elegant powder blue,” the colour of the Beat album cover, and thus a reminder of the “moving wheels” of the album’s first track.

His “body” is “sleeping in the jungle of…metal relics,” reinforcing the identifying of the human body and of nature with metal, machines, cars, and other forms of modern technology. Recall that Ginsberg was making similar complaints about how modern industrial capitalism is driving us all mad, in the Moloch passages of “Howl.” We can see in this verse of “Dig Me” how it develops the themes of the Right Side of Three of a Perfect Pair: modern industry has resulted in a decline in the quality of our lives. “What was deluxe becomes debris.”

No Warning

At first, I had difficulty figuring out where this instrumental improvisation would fit into the overall themes of this album, given the vagueness of the track’s title (no warning of what?). Then I discovered these outtakes, “Industrial Zone A” and “Industrial Zone B,” and on hearing their sonic similarity to “No Warning,” now I know how to interpret them.

“No Warning,” therefore, is a sequel instrumental to “Industry.” It’s not that no warning was ever given: lots of leftists back in the 1980s warned what the policies of politicians like Reagan and Thatcher would lead to; it’s that no warning was heeded by the mainstream population.

The music of this instrumental is even darker and more ominous than that of “Industry” because, if we see these two tracks as musical chronicles of modern history, then where “Industry” gave us the beginning and early growth of industrial capitalism, “No Warning” gives us the late-stage capitalism of the mid-1980s and since then. Things have gotten far, far worse, with not only the rise of neoliberal reactionaries, but also the increasing damage being done to the Earth.

The use of high-tech instrumentation, such as guitar synthesizers, the Stick, and electronic drums, can be heard as an ironic commentary on how technology isn’t always a good thing (e.g., nuclear weapons). Of course, we get more of Belew’s mechanical guitar sounds as part of this commentary; notice also the conspicuous absence of animal noises from his guitar, since in our day, animals are fewer and fewer; a further discussion of that issue is coming shortly. Bruford’s bashing of his drum kit in free rhythm, combined with the guitar dissonances, just adds to the feeling of dystopian unrest. The dark tones from Levin’s Stick, played as they seem to be through a volume pedal, top off the eerie atmosphere.

Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part III

This instrumental is yet again an example of “three of a perfect pair,” the pair in this case being parts one and two of “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic,” the first and last tracks of the album of the same name, released back in 1973, and the first Crimson album to have Bruford on drums, since he’d just left Yes after finishing Close to the Edge.

This third part opens with Fripp playing fast arpeggios that shift back and forth between tonality and atonality, a Frippian idiosyncrasy we’ve heard a number of times before, such as on a few tracks on Exposure, in collaborations with Daryl Hall around the same time, and most significantly, at one point in the middle of “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part One,” a passage that in turn has a precedent in an instrumental recorded, but not yet released, by the Islands Crimson lineup.

After this comes a guitar-dominated riff in a cycle of two bars of 4/4, then one in 2/4, repeated several times. The crunchy guitar chords vaguely remind one of those played by Fripp at the beginning of “Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, Part Two.” The rest of the music of Part Three bears hardly any resemblance to that of the first two parts.