I: Introduction

“Howl” is a poem by Allen Ginsberg, written in 1954-1955 and dedicated to Carl Solomon, hence it’s also known as “Howl for Carl Solomon.” It was published in Ginsberg’s 1956 collection, Howl and Other Poems.

“Howl” is considered one of the great works of American literature. Ginsberg being one of the writers of the Beat Generation, “Howl” reflects the lifestyle and preoccupations of those writers–Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady (“N.C., secret hero of these poems”; also, “holy Kerouac […] holy Burroughs holy Cassady”), etc.

The preoccupations of the Beat Generation writers included such subculture practices (as of the conservative 1950s, mind you) as drug use, homosexuality, free love, interest in non-Western religions, etc. Such practices are described with brutal, uncensored frankness in “Howl,” hence the poem was the focus of an obscenity trial in 1957.

Here is a link to the entire poem, and here is an annotated version of it (without the ‘footnote’).

The very title of the poem, one that gives vivid description to so much suffering, must be–on at least an unconscious level–an allusion to the final scene in King Lear, when the grieving king enters, carrying his freshly executed daughter, Cordelia. He calls out “Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones!” As in “Howl,” King Lear demonstrates, as I argued in my analysis of the play, that in the midst of so much suffering and loss, one can also gain something: Lear loses everything, but he also gains self-knowledge. Similarly, “the best minds of [Ginsberg’s] generation” suffered much and engaged in much self-destruction, but they also searched for forms of spiritual enlightenment, as I’ll demonstrate below. By the ‘footnote‘ section of the poem, we’ll find Ginsberg gaining that “Holy!” enlightenment.

II: Part I of the Poem

Now, “the best minds of [Ginsberg’s] generation” were those Beat Generation writers and their socially non-conforming ilk, engaging in all the wild behaviour we associate with them–doing drugs, having promiscuous sex, etc. As a result, they have been “destroyed by madness,” and have been “starving hysterical naked.”

“Naked” could be a reference to illicit sex, but it more likely refers to a lack of possessions in general, as the word is used in Hamlet, Act IV, Scene vii (in which Hamlet writes, in a letter to Claudius, “I am set naked on your kingdom.”). After all, these “best minds” are “starving hysterical naked.” Their wildness comes in large part because of their poverty, the cause of which, in turn, is an issue I’ll delve into in more detail later.

These drug addicts are going “through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix”, yet in spite of their Dionysian sinfulness, they’re also “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection”. They seem to be offering their own idiosyncratic interpretation of Luther’s injunction to “sin boldly.”

Indeed, there is a duality permeating these pages, cataloguing on the one hand sin, obscenity, and excess, and on the other, a search for spirituality and salvation. They are in “poverty and tatters […] high […] smoking” and “contemplating jazz,” for this music was an important soundtrack to the lives of the Beats, as one can note many times reading Kerouac’s On the Road. Yet they also “bared their brains to Heaven under the El and saw Mohammedan angels…”

The El is the elevated train in New York, but it’s also a Hebrew name for God. Note also that the words “Mohammedan” and “negro” were being used here before they were considered unacceptable. Ginsberg’s reference to the Muslim faith is one of many examples of the Beats taking spiritual inspiration from non-Western sources. Some Beats having hung out in Tangiers (in the International Zone in particular) can, in part, be seen as an example of this influence.

The use of “who” beginning many of the long lines of this first part of “Howl” is paralleled with the refrains of “Moloch” in Part Two, “I’m with you in Rockland” in Part Three, and “Holy” in the ‘footnote.’ “Who” reminds us that the subject of Part One, an almost interminable sentence, is Ginsberg’s beatnik friends. The refrains of the other three parts also, of course, remind us of their respective subjects, an explanation of which will come when I get to those parts below.

Special attention should be given to Ginsberg’s use of long lines, something he derived from Walt Whitman, whose non-conforming behaviour (including homosexuality) could make him a kind of Beat Generation poet of the 19th century. One could compare these long lines to the sometimes lengthy verses of the Bible, giving Whitman’s and Ginsberg’s poetry a near-sacred feel, in spite of (or perhaps because of) its sensuality (recall in this connection the sensuality of the Song of Solomon… could the dedication to Carl Solomon be linked to this Biblical association?).

Long lines are oceanic, inclusive, requiring deep breaths to take in everything before expressing everything. They are universal because the poetry of Whitman and Ginsberg is universal: these two men are bards of Brahman, seeing holiness in everything (read Ginsberg’s “footnote” to see what I mean). The two poets embrace all religious traditions, like Pi, but they also reject the limitations of any one religious tradition or dogma. These long lines, in including everything but eschewing the rigidity of traditional short and exact metres, exemplify the same paradox in poetry.

In “Blake-like tragedy”, we find another example of a spiritual non-conformist in whom Ginsberg found inspiration. I discussed William Blake‘s unconventional approach to Christianity in the “Jerusalem” section of this analysis of an ELP album.

Ginsberg was once “expelled from the academies for crazy […] obscene odes…”, that is, he was kicked out of Columbia University for writing obscenities on his dorm room window. His friends “got busted in their pubic beards returning through Laredo with a belt of marijuana for New York,” that is, they were caught in Laredo with weed stashed in their underwear.

They “ate fire” and “drank turpentine in Paradise Alley…”, referring to the ingesting of toxic substances (drugs and alcohol) in a slum in New York City, full of run-down hotels, brothels, and dope dealers. Nonetheless, in a poem, Paradise Alley also has heavenly associations, and thus in this line we have another juxtaposition of the sinful with the spiritual.

Those readers who may have difficulty reconciling my close associating of sin with mysticism should take into account the idea of the dialectical unity of opposites, an idea I’ve symbolized with the image of the ouroboros in a number of blog articles. Two extreme opposites meet, or phase into each other, where the serpent’s head bites its tail, and all intermediate points are found in their respective places along the middle of the ouroboros’ body, coiled into a circular continuum.

Applied to “Howl,” this means that the harshest Hell phases into the highest Heaven and vice versa. One cannot understand this idea while adhering to traditional Christian dogma and its literal reading of an eternity in either Heaven or Hell. My interpretation of the ‘afterlife’ is metaphorical. In our moments of darkest despair, we often see the light and come out the other side (“It’s always darkest before the dawn.”); this is what Christ‘s Passion, harrowing of Hell, and Resurrection symbolize. Note also that those who rise to the highest points of pride tend to fall, as Satan and the rebel angels did. Finally, keep in mind the Beatitudes—Matthew 5:4 and 5:11-12 in particular.

This Heaven/Hell dialectic can be seen in the four parts of “Howl.” This first part is the Hell thesis, with the second, “Moloch” part representing the Satanic cause of that Hell; the “Rockland” third part is the Purgatory sublation (though therapy in an insane asylum must be judged to be a remarkably ill-conceived purging of sin), and the “footnote” is the antithesis Heaven that stands in opposition to this present first part.

In this way, we can see “Howl” as Ginsberg’s modern Beat rendition of Dante‘s Divine Comedy. And just as Dante’s Inferno is the most famous first part of his epic poem, so is the infernal first part of “Howl” the most famous part, with its emphasis on human suffering. Similarly, Pasolini‘s Salò, with its sections divided up into Circles of Manias, Shit, and Blood–like Dante’s nine circles of Hell–is also focused on suffering, sin, and sexual perversity.

To come back to the last line discussed before my dialectical digression, and to link both discussions, this inferno part makes fitting reference, in this line, to the paradiso of Paradise Alley and the purgatorio of the “purgatoried […] torsos”. These torsos may be purged of sin through the ingesting of alcohol and drugs, or through sex (“pubic beards”, “torsos”, and “cock and endless balls”).

Just as there’s a dialectical unity of Heaven and Hell (i.e., one must go through Hell to reach Heaven, as Jesus did, the passing through the ouroboros’ bitten tail to get to its biting head), so is there also a dialectical unity of sin and sainthood (i.e., one uses drugs or sexual ecstasy to have mystical visions or spiritual ecstasy). The fires of Hell are those of desire, in samsāra; blowing out the flame leads to nirvana. The Mahayana Buddhist tradition, however, sees a unity between samsara and nirvana–the fire is the absence of fire…Heaven is Hell. The Beats, in their excesses, understand these paradoxes.

Part of those Dionysian excesses are, as mentioned above, the alcohol and drug abuse (“peyote” and “wine drunkenness over the rooftops”). Similarly, the Beats were “chained […] to subways for the endless ride from Battery to holy Bronx on benzedrine“, that is, they were so high on the benzedrine that they were frozen from doing anything while on their endless joyride on the subway, “chained” to it, all the way from Battery to the Bronx. Note how the Bronx is “holy”: in their sinful indulgence on drugs, the beatniks attain sainthood in the Bronx.

At Fugazzi’s…Bar and Grill, at 305, 6th Ave. in New York City?…they are “listening to the crack of doom on the hydrogen jukebox”. In Macbeth, “the crack of doom” is the end of the world, and a “hydrogen jukebox” suggests the hydrogen bombs that had been created, recently as of the writing of “Howl,” a bomb whose destructive power, greater than the original atomic bomb, can bring us even closer to “the crack of doom.”

Ginsberg and company, however, are getting wasted listening to music–jazz, presumably, on the jukebox. They are creating their own armageddon of drunken self-destruction. That end of the world, though, is followed by the Kingdom of God: the beatniks, in their rejection of the conservative values of the nuclear family, are getting nuclear bombed drunk; and the hellish fires of “the crack of doom,” the ouroboros’ bitten tail, will be passed through to attain the heavenly Kingdom of God, the serpent’s biting head.

The dialectic is manifested once again in how this “lost battalion of platonic conversationalists” are “jumping down the stoops off fire escapes off windowsills off Empire State…” Since sorrows “come not single spies but in battalions,” it’s easy to see them leading to despair and suicide. Yet the beatniks would express platonic ideals in philosophical discussion, an Apollonian trait; of course, in true Dionysian fashion, they would also jump off of buildings to their deaths to escape the egoistic experience for that of the oneness of Brahman.

Thus, the juxtaposition of jumping suicides with platonic conversation is a case of “whole intellects disgorged […] for seven days and nights”…the seven days and nights of Biblical creation, ending in a day and night of rest–that Heaven of intellectual bliss? It’s fitting to include the Sabbath–“meat for the Synagogue”, since Ginsberg was Jewish.

Indeed, the Beats return from debauchery to spirituality in not only the Synagogue, but also “Zen New Jersey”, “suffering Eastern sweats and Tangerian bone-grindings and migraines of China under drunk withdrawal”. We’re reminded of the Opium Wars, the victimizing of China under Western imperialism, and maybe the jumping “off Empire State” is Ginsberg’s rejection of that very imperialism.

These hipsters “studied Plotinus Poe St. John of the Cross telepathy and bop kabbalah because the cosmos instinctively vibrated at their feet in Kansas”. Plotinus was a neoplatonist who believed that all of reality is based on “the One,” a basic, ineffable state beyond being and non-being, the creative source of the universe and the teleological end of all things. St. John of the Cross was a Spanish mystic and poet who wrote The Dark Night of the Soul, both a poem and a commentary on it that describe a phase of passive purification in the mystical development of one’s spirit.

What’s interesting here is how Ginsberg sandwiches, between these two writers of spiritual, philosophical matters, Edgar Allan Poe, also a great writer, but one whose death at the relatively young age forty was the self-destructive result of alcoholism, drug abuse, and/or suicide, his last moments having been in a delirious, agitated state with hallucinations.

Though St. John of the Cross hadn’t intended this meaning, “the dark night of the soul” has the modern meaning of ‘a crisis in faith,’ or ‘an extremely difficult or painful period in one’s life.’ The combining of these three writers in the above-quoted line in “Howl” suggests a dialectical thesis, negation, and sublation of them respectively: the wisdom of philosophy (Plotinus), the destructiveness of the Dionysian way (Poe), and a combination of passive mystical purification with a spiritual crisis and a painful time in life (St. John of the Cross).

Such an interpretation dovetails well with the Heaven and Hell, saintly sinner theme I’ve been discussing as running all the way through Ginsberg’s poem. The juxtaposition “bop kabbalah” continues that theme, with “bop” representing the contemporary jazz that he and his beatnik pals were grooving to while drunk or stoned, and “kabbalah” representing Jewish mysticism, a fitting form of it for Ginsberg.

This “bop kabbalah” dialectic is further developed in how “the cosmos instinctively vibrated at their feet in Kansas,” since Kansas was the Mecca of jazz and bebop for hipsters at the time; and a ‘vibrating cosmos’ suggests the oceanic waves of Brahman, or Plotinus’ One. The hipsters were also going “through the streets of Idaho seeking visionary Indian angels…”, even more of a juxtaposition of the common and the cosmic.

They’d be “seeking jazz or sex or soup”, and they would “converse about America and Eternity”. These hipsters led bohemian lives, but also wanted to know the rest of the world, so by “America” it is not meant to be only the US but also Latin America–the Mayan ruins of Mexico. To escape the evil of American capitalism, Ginsberg “took ship to Africa”. These are examples of the Beats immersing themselves in the wisdom of other cultures. The protesting of capitalism is part of the basis of the Beats’ destructive Dionysian non-conformity; hence, they “burned cigarette holes in their arms”.

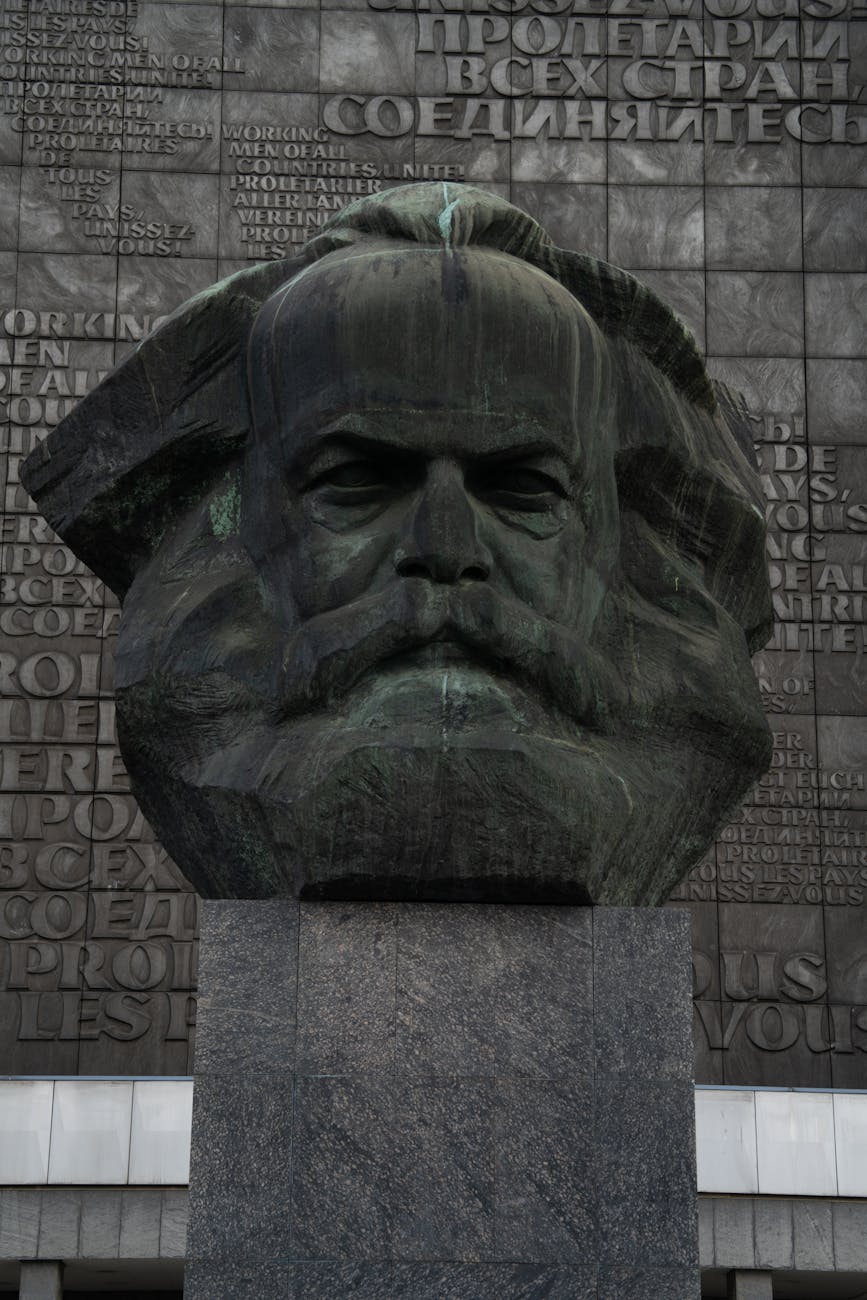

Note how the Beats’ protesting of “the narcotic tobacco haze of capitalism”, having “distributed Supercommunist pamphlets” would have been done in 1950s America, at a time of welfare capitalism, higher taxes for the rich, and strong unions. Imagine the passion the Beats would have had distributing “Supercommunist pamphlets” in today’s neoliberal nightmare of a world!

They “bit detectives in the neck”, those protectors of private property and the capitalist system. Recall how Marx compared capitalists to vampires, as Malcolm X called them bloodsuckers; Ginsberg’s vampire-like Beats biting cops’ necks is indulging in amusing irony here. After all, he insists that the Beats’ non-conforming sexuality and intoxication are “committing no crime”. They “howled on their knees in the subway […] waving genitals…”

More obscenity and saintliness are merged when Ginsberg says they “let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists and screamed with joy.” This line in particular got him in trouble with the law, though in the end, “Howl” was ruled to have “redeeming social importance.” Similarly, the Beats “blew and were blown by those human seraphim”, and “balled in the morning in the evening […] scattering their semen freely…”

When a “blond and naked angel came to pierce them with a sword”, we see an allusion to The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, a fusion of sexual ecstasy with spiritual ecstasy.

Now, “the three old shrews of fate” who have taken away the Beats’ boy lovers are the Moirai. These can be seen to personify the kind of conformist, nuclear family that the Beats are rebelling against. Each shrew is one-eyed, for in her conformity, she cannot see fully. One is “of the heterosexual dollar”, a slave to the capitalist, patriarchal family, and in her complaining of her lot in life, she seems shrewish. One shrew “winks out of the womb”, since by limiting her life to that of a career mother, she also sees little. The last shrew “does nothing but sit on her ass and snip the […] threads of the craftsman’s loom”; she is Atropos, who in cutting the thread ends people’s lives, yet in limiting herself to doing traditional women’s work, she’s ending her own life, too.

The Beats “copulated ecstatic and insatiate […] and ended […] with a vision of ultimate cunt and come eluding the last gyzym of consciousness”. Here again, we see Ginsberg uniting the sexual with the “ecstatic” spiritual: in “ultimate cunt”, we have a fusion of the final with the beginning of life; similarly, “come” and “gyzym” would begin life, yet here we have “the last” of it. The end is dialectically the beginning–the Alpha and the Omega, the eternal, cyclical ouroboros.

Such heterosexual Beats as “N.C.”, or Neal Cassady, “sweetened the snatches of a million girls”. He “went out whoring through Colorado in myriad stolen night-cars”. Indeed, a reading of On the Road will reveal how Cassady (i.e., Dean Moriarty) did exactly this.

When it says that the Beats “ate the lamb stew of the imagination”, since there’s so much juxtaposition of sensuality with spirituality in “Howl,” I suspect that “lamb” here refers at least in part to the Lamb of God. Ginsberg may have been Jewish, but as a Beat poet, he would have been interested in religious and spiritual traditions outside of his own. The ‘eating of the lamb stew of the imagination’ would thus be yet another example of “Howl” fusing the sensual and the spiritual.

The Beats were “under the tubercular sky surrounded by orange crates of theology,” yet another example of such fusions, as is “rocking and rolling over lofty incantations”. They “threw their watches off the roof to cast their ballot for Eternity outside of Time,” indicating a preference of the transcendent over the mundane; yet they’ve also engaged in suicidal acts, indicating the despair that bars one from entry to Heaven. Such suicidal acts include “cut[ting] their wrists three times successfully unsuccessfully,” as well as having “jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge this actually happened”.

Some Beats were “burned alive in their innocent flannel suits”, an apparent allusion to The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, by Sloan Wilson, another Beat book. One Beat, Bill Cannastra, was with those “who sang out of their windows in despair, fell out of the subway window”: Cannastra died drunkenly trying to exit a moving subway car.

Some “danced on broken wineglasses barefoot”. Some went “journeying to each other’s hotrod Golgotha jail-solitude watch or Birmingham jazz incantation”. Again, we see a merging of the sensual (“wineglasses,” “jazz,” “hotrod”) and the spiritual (i.e., the Christian imagery of “Golgotha”), as well as a fusion of salvation (Christ’s crucifixion at Golgotha, the place of the skull) and condemnation (“jail”).

The Beats hoped, in their travels, “to find out if I had a vision or you had a vision or he had a vision to find out Eternity”. They were often in Denver, as Kerouac and Cassady were (represented by Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, respectively) in On the Road. All of the drinking and partying therein is Dionysian mysticism, if properly understood.

For in spite of how antithetical this drunken partying may seem to the spiritual life, the Beats also “fell on their knees in hopeless cathedrals praying for each other’s salvation”. The cathedrals were “hopeless” because there’s no salvation in conventional, orthodox religion.

So instead, they “retired to Mexico to cultivate a habit, or Rocky Mount to tender Buddha or Tangiers to boys […] or Harvard to Narcissus…” Alternative forms of spirituality may have been Buddhism (consider Kerouac and The Dharma Bums), or the dialectical opposite of spirituality, indulgence in drugs or pederasty, or a generally narcissistic attitude. In any case, the “hopeless cathedrals” would never have sufficed for the Beats.

Just as there’s a fine line between Heaven and Hell as described in “Howl,” so is there a fine line between genius and madness here. Ginsberg has celebrated the inspired creative genius of Kerouac, Cassady, Burroughs…himself in this very poem…and others. Ginsberg has demonstrated many of the acts of madness of the Beats. Now we must examine the attempts ‘to cure’ madness.

Now, what must be emphasized here is that it’s not so much about curing mental illness as it is about taking non-conforming individuals and making them conform. Recall that at this time, the mid-20th century, homosexuality was considered a form of mental illness. The proposed cures for these ‘pathologies’ were such things as lobotomy, “Metrazol electricity hydrotherapy psychotherapy occupational therapy pingpong…”

Recall that “Howl” is dedicated to Carl Solomon, who voluntarily institutionalized himself, “presented [himself] on the granite steps of the madhouse…” Solomon, mental institutions (what Ginsberg calls “Rockland”), and pingpong will return in Part Three of this poem.

The psychotherapy in these mental institutions will include such fashionably Freudian ideas as the Oedipus complex, as we can see in Ginsberg’s line about “mother finally ******”. The ultimate narcissistic fantasy, about sexual union with the mother, Lacan‘s objet petit a, has to have a four-letter word censored, for a change in this poem, since it’s a gratification too great for even Ginsberg to discuss directly: “ah, Carl, while you are not safe I am not safe…”

Still, while mired not only in madness but, worse, also in the prisons of psychiatry–those cuckoo nests–these incarcerated Beats can still experience the divine. They have “dreamt and made incarnate gaps in Time and Space […] trapped the archangel of the soul […] jumping with sensation of Pater Omnipotens Aeterna Deus…”

This connection with the divine is achieved through the use of language, a kind of talking cure, entry into the cultural/linguistic world of Lacan‘s Symbolic, as expressed in Ginsberg’s poetry and the prose of Beats like Kerouac and Burroughs. They’ll use “elemental verbs and set the noun and dash of consciousness […] to recreate the syntax and measure of poor human prose…”

The Beats are thus a combination of “the madman bum and angel beat in Time,” a marriage of Heaven and Hell (recall the “Blake-like tragedy” above), the best and the worst, “speechless and intelligent and shaking with shame,…” They “blew the suffering of America’s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabachthani saxophone cry…” In this, we see how the Beats combine jazz sax partying with suffering, despair, Lamb-of-God salvation and love.

“Howl” describes the individual experiences of men like Cannastra, Cassady, Kerouac, Solomon, and Ginsberg as if all the Beats had experienced them collectively, since in their solidarity of non-conformity, they felt the Dionysian unity, Plotinus’ One, Brahman’s nirvana. Ginsberg will feel that solidarity with Solomon in Part Three, but first,…

III: Part II of the Poem

Note how Moloch is described as a “sphinx of cement and aluminum” who “bashed open [the Beats’] skulls and ate up their brains and imagination”. Moloch, an ancient Canaanite god depicted in the Bible and understood to have been one requiring child sacrifice, is a Satanic figure in “Howl,” the Devil responsible for the Inferno of Ginsberg’s Divine Comedy here. But what does this Satanic figure in turn represent?

The “sphinx of cement and aluminum” that is also “Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars” is modern-day industrial capitalism. Children are sacrificed to this Moloch, this Mammon of money, by having their skulls bashed open and their brains and imagination eaten. In our education systems, children’s energy, individuality, and creativity are all stifled and replaced with obedience and conformity, that energy redirected towards making money for the Man, never for the people, for whom it’s “unobtainable.”

The “Solitude” of Moloch is alienation, the lack of togetherness among people, which has been replaced by cold-blooded competition. This had led to “Children screaming under the stairways!”

In this second part–instead of the preceding part’s long lines ending in commas, which suggested an ongoing problem seemingly without end, the hopelessness of eternal infernal punishment–we have lines ending in exclamation points, to express the rage Ginsberg feels against an economic system to which we all feel we’ve had to sell our souls. Small wonder the non-conforming Beat writers were going mad in a drunken, Dionysian frenzy.

Moloch is an “incomprehensible prison!” It’s a “soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments!” Ginsberg recognizes, as so many right-wing libertarians fail to do (or are dishonest about not recognizing), that capitalism very much requires a state and a Congress to make laws that protect private property. Government only does socialist stuff when it’s a workers’ state, not the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, as the US has always been.

These “buildings [of] judgment” that are “the vast stone of war” are symbols of the modern, industrial world. The capitalist government has far too little funding for the poor, for education, for healthcare or for affordable housing, but it has plenty of money for the military. The Moloch government is “stunned” because it’s confused over who should have access to this tax revenue.

The evil industry of capitalism “is pure machinery!” It’s “blood is running money!” Since capitalism in our modern world spills into imperialism, as Lenin pointed out, then it’s easy to see how money can be linked with blood, death, and human suffering in war. Moloch’s “fingers are ten armies!” These are the armies of the Americans who, already in the 1950s, were occupying South Korea, making their women into prostitutes for the enjoyment of the GIs, and making their men fight their brothers and sisters in the north. Moloch’s “ear is a smoking bomb”, like those dropped all over North Korea.

The specifically modern, industrial nature of the capitalism that Ginsberg is excoriating here is found in such lines as this: “Moloch whose skyscrapers stand in the longs streets like endless Jehovahs! Moloch whose factories dream and croak in the fog! Moloch whose smoke-stacks and antennae crown the cities!”

These skyscrapers will be office buildings, places of business, the nerve centres of capitalism. Just as Moloch and Mammon are false gods, so are the “endless Jehovahs” a heathenizing of the Biblical God by pluralizing Him. The irony mustn’t have been lost on Jewish Ginsberg to know that Elohim can be the one God of the Bible as well as the many gods of paganism. Indeed, Judeo-Christianity has often been used to justify capitalism, imperialism, and settler-colonialism.

Moloch’s “love is endless oil and stone!” Note the endless coveting of oil in the Middle East. This would have been evident to Ginsberg as early as 1953, when the coup d’état in Iran happened to protect British oil interests in the region. The indictment against capitalism continues in these words: “Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks!”

Note also that Moloch’s “poverty is the specter of genius!” By “genius,” we can easily read Communism, since European poverty in the mid-19th century inspired the spectre that was haunting the continent.

“Moloch in whom I sit lonely! Moloch in whom I dream Angels! Crazy in Moloch! Cocksucker in Moloch! Lacklove and manless in Moloch!” Again, Ginsberg addresses the problem of alienation caused by capitalism. He also explains in this long line how one resolves the contradiction between sinning and the pursuit of salvation. One “dream[s of] Angels” in a desperate attempt to escape Moloch’s inferno. Still, that very desperation, in finding the escape so impossible, causes one to go “Crazy in Moloch!”

Conservative society’s moralistic condemnation of homosexuality, something gay Ginsberg would have been more than usually sensitive to, reduced his form of sexual expression to mere pornographic language, hence “Cocksucker in Moloch!” Recall Senator Joseph McCarthy‘s vulgar homophobia when he said, back at a time when such language would have been far more shocking, “If you want to be against McCarthy, boys, you’ve got to be either a Communist or a cocksucker.” Of course, the taboo against homosexuality was so aggravated at the time that it would have been so much more difficult for LGBT people like Ginsberg to find love, hence “Lacklove and manless in Moloch!”

“Moloch…entered [his] soul early!” It brainwashed him as a child into thinking he needed to conform to the ways of a capitalist, heterosexual society. He’d later have to work to unlearn all of that poisonous conditioning. “Moloch…frightened [him] out of [his] natural ecstasy!” He had to “abandon” Moloch.

Moloch is an industrial capitalist world of “Robot apartments!” (Imagine how much more robotic they’re becoming now, in our world of smart cities, with AI surveillance.) The “blind capitals! demonic industries!…invincible madhouses!” [to be dealt with in the next part] “granite cocks! monstrous bombs!” are those of a capitalist state, far more totalitarian than a socialist one could ever be.

“They broke their backs lifting Moloch to heaven!” Those phallic skyscrapers are “granite cocks!” Moloch is “lifting the city to Heaven”, with these skyscrapers as Towers of Babel: this tireless, slavelike construction has confused our language, making us incapable of communicating with or understanding each other, more capitalist alienation.

The pain and Hell of Moloch’s Inferno, though, is also in close proximity, as I described above, with the Heaven, the Paradiso, to which the Beats were trying to escape. Hence, “Visions! omens! hallucinations! miracles! ecstasies!” One has mystical experiences of bliss and psychotic breaks from reality at the same time. One thus also has “Dreams! adorations! illuminations! religions! the whole boatload of sensitive bullshit!” One has “Breakthroughs!…flips and crucifixions!…Highs! Epiphanies! Despairs!…suicides!…Mad generation!”

Though this is the Hell of Moloch, there is also “Real holy laughter…!…the holy yells!” The “Howl! Howl! Howl!” of Hell leads to holiness, that passing from the bitten tail of the ouroboros to its biting head. To reach the very best, one must pass through the absolute worst.

Still, some tried to purge the Beats through the dubious mental institutions, and this is where we must go next…

IV: Part III of the Poem

This part of “Howl” is most directly addressed to Carl Solomon, to whom, recall, the entire poem is dedicated–this ‘Song of Solomon,’ if you will. Ginsberg met Solomon in a mental hospital in 1949; he calls it “Rockland” in the poem, though it was actually Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute. In fact, among Solomon’s many complaints about Ginsberg and “Howl” was his vehement insistence that he was “never in Rockland” and that this third part of the poem “garbles history completely.”

As much of a fabrication as “Rockland” is, though, we can indulge Ginsberg in a little poetic license. After all, “Rockland” has a much better literary ring to it than “Columbia Presbyterian Psychological Institute,” or “New York State Psychiatric Institute,” or even “Pilgrim Psychiatric Center,” this latter being another psychiatric hospital to which Solomon was admitted.

In any case, maybe the point isn’t so much about Ginsberg being literally, physically with Solomon in the correctly-named mental institution, but rather that the poet was with Solomon in spirit, in solidarity with him, in a metaphorically therapeutic state of being, a true purging of Solomon’s sin and pain, which Ginsberg called “Rockland.” As such, this ‘mental hospital,’ as it were, is the Purgatorio that the actual hospital could never have been. The actual hospital would have just pushed conformity onto Solomon. The solidarity of Ginsberg and the other Beats, being with Solomon “in Rockland,” is the real cure.

So as I see it, the refrain “I’m with you in Rockland” means that Ginsberg was in solidarity with Solomon in his process of mental convalescence, a far better healer than the best shrinks in his actual loony bin. Ginsberg’s love and friendship, as that of all the other Beats, is a therapy to make that of his doctors and nurses seem like wretched Ratcheds in comparison. This part of “Howl” is the Purgatorio because of the Beats, not because of the therapists.

Solomon is “madder than” Ginsberg is, in both senses: more insane, and so voluntarily in a mental institution that the poet is only visiting; and angrier, because of the conformist society he was so at odds with that he chose to be put in the institution.

Solomon “imitate[s] the shade of [Ginsberg’s] mother”, who also had mental health issues, and so Ginsberg’s love for her inspired his empathy for Solomon. Similar empathy can be seen between Ginsberg, Solomon, and all the other Beats, since they were all “great writers on the same dreadful typewriter”–the Beats tended to type, rather than write, their literary works. Recall the caustic words of Truman Capote about the Beats: It “isn’t writing at all–it’s typing.”

Recall how the first part of “Howl” had its lines ending in commas, making it one interminable sentence with only breaths to break it up. The second part had its thoughts ending in a plethora of exclamation marks…endless screaming about the agonies that Satanic Moloch was inflicting on all the Beats. In this third part, however, there are neither commas nor exclamation marks. No periods, parentheses, or dashes, either. There’s no punctuation at all, unless you count the apostrophe in “I’m”. This lack of an indication of pauses suggests a kind of rapid-fire speaking, a frantic dumping-out of words, a therapeutic release of feelings that have been pent up for far too long. Such expression is a true purging of pain.

Now, in direct contrast to this verbal purging, this Symbolic expression of the undifferentiated, ineffable Real, Solomon suffered from the staff of the mental hospitals and their bogus therapy. The “nurses [are] the harpies of the Bronx”. He would “scream in a straitjacket that [he was] losing the game of the actual pingpong of the abyss.” I assume that a pingpong table was provided in Solomon’s hospital, in an abortive attempt to allow the patients to enjoy themselves.

He would “bang on the catatonic piano”, trying and failing to express himself artistically on instruments presumably also provided by the hospital. The immobility of catatonia, a perfect metaphor for the lifelessness of the patients, results in discords ‘banged on the piano’ instead of flowing, expressive music.

One’s innocent soul “should never die ungodly in an armed madhouse […] where fifty more shocks will never return your soul to its body”. This, of course, is a reference to the particularly egregious practice of electroshock treatments for the mentally ill. Ginsberg felt that shock therapy robbed Solomon of his soul. This practice is critiqued in Ken Kesey‘s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Solomon would “accuse [his] doctors of insanity”, given such truly psychopathic practices as described in the previous paragraph. Indeed, this Purgatorio of Ginsberg’s poem, set in a mental institution, is ironic in how the opposite of purgatory occurs here, where a restoration to mental health is expected, while the friendship and solidarity Ginsberg has with Solomon is the real cure.

Ginsberg and Solomon, both Jews, would “plot the Hebrew socialist revolution against the fascist national Golgotha”, the American political establishment of the 1950s that was right-wing and, ironically, Christian. American imperialism crushes revolutionaries just as Roman imperialism crucified Christ. The Rockland “comrades [will be] all together singing the final stanzas of the Internationale.”

The American government, whose FBI and CIA were monitoring men like Ginsberg in the 1950s for their subversive activities, “coughs all night and won’t let [them] sleep”.

Their “souls’ airplanes” will “drop angelic bombs”, and the “imaginary walls” of the hospital will “collapse”. The “skinny legions” thus can “run outside […] O victory forget your underwear we’re free”. As I said above, the true healing from mental illness will come outside of the mental institutions, not inside them. Without underwear, the freed inmates will be naked, allowed to be their true selves, with no need to cover up who they really are.

Solomon thus will go “on the highway across America in tears to the door of [Ginsberg’s] cottage”. This cottage will be the locale of restoration to mental health that the loony bins could never be. His cottage will be the real purgatory, cleansing all the Beats of their sins and readying them for Heaven, for Ginsberg’s Paradiso, which is…

V: Footnote to Howl

Allegedly, Ginsberg stated in the Dedication that he took the title for the poem from Kerouac. I still believe, however, that the title for “Howl” was inspired, whether in the conscious or unconscious of Ginsberg or Kerouac, by Lear’s repeated cry of “Howl!” over Cordelia’s death.

I insist on this allusion in part because of how the “footnote” begins, with its uttering of “Holy!” fifteen times. On the one hand, “Holy!” can be heard as a pun on “Howl!” On the other hand, “Holy!” is the dialectical opposite of “Howl!” It is yet another instance of the Heaven/Hell dialectic that permeates the entire poem.

This repetition of “Holy!” implies the repetition of the title, just as Lear repeated the word four times.

Like the second part, the ‘footnote’ ends each statement with an exclamation point. The second part, with its Satanic Moloch, is like the Centre of Hell in its Ninth Circle, as depicted by Dante in his Inferno. This area is the worst part of Hell, where Satan is trapped waist-deep in ice, his three faces’ mouths feasting on Brutus, Cassius, and Judas Iscariot.

My point is that the same punctuation is used in the very worst and best places in “Howl.” Here is where the bitten tail of the ouroboros, where Satan’s mouths are feasting, leads immediately to the serpent’s biting head of Heaven, Ginsberg’s Paradiso. The exclamation points represent screams of horror in the “Moloch” part, and screams of joy in this “Holy!” footnote.

“Everything is holy!” to Ginsberg. “The world is holy! The soul is holy!” As a convert to Buddhism, following such Mahayana forms as Tibetan Buddhism, Ginsberg would have understood the unity of samsara and nirvana. So while all life is suffering, or the duhkha of samsara, it’s all manifestations of Buddha-consciousness, too, or “Holy!” Once again, Heaven and Hell are unified.

Even the ‘sinful’ or dirty parts of the body are holy: “The tongue and cock and hand and asshole holy!” Furthermore, “everybody’s holy! everywhere is holy!”

“The bum’s as holy as the seraphim! the madman is holy as you my soul are holy!” People from the lowest ranks of society to the highest orders of angels are of equal worth, the greatest worth…holy!

The typewriter may have been “dreadful” back in the third part of “Howl,” but here it’s holy, as “the poem is holy”. Of course, the Beats are holy, including Ginsberg himself, Solomon, Kerouac, Burroughs, and Cassady, “the unknown buggered and suffering beggars holy the hideous human angels!”

Ginsberg must also acknowledge the sanctity of his “mother in the insane asylum!” He similarly praises the sanctity of “the groaning saxophone!…the bop apocalypse! Holy the jazzbands marijuana hipsters peace peyote pipes and drums!”

While he condemned the skyscrapers of Moloch in the second part, here he sees them as holy, as well as the solitude of alienation he called evil earlier. The “mysterious rivers of tears under the streets!” are also holy. What is painful is also divine. Heaven and Hell are one. So the “lone juggernaut,” a Hindu god whose worship was once believed in the West to involve religious fanatics throwing themselves before its idol’s chariot, to be crushed under its wheels, is actually holy and good.

“Holy the vast lamb of the middleclass!” The petite bourgeoisie of 1950s American would still have been predominantly Christian, of the Lamb of God, and thus disapproving of Ginsberg’s homosexuality, but he deems them holy nonetheless, as he does “the crazy shepherds of rebellion!” And since Jesus was “the good Shepherd,” we can see in these “shepherds of rebellion” another paradox of conformist Christian with rebellious Beats.

He praises as holy many cities of the world, including New York, San Francisco, Paris, Tangiers, Moscow, and Istanbul, reinforcing the sense of a pantheistic universe.

Ginsberg, as a gay activist and socialist, was somewhat disenchanted with, for example, the social conservatism he saw in Cuba and its persecution of homosexuals in the mid-1960s, as well as with China, who turned against him as a “troublemaker,” and with Czechoslovakia’s arresting him for drug use. Because of these kinds of disappointments (these above examples having happened long after the writing and publication of “Howl,” of course, but still illustrative of the general kind of disillusion he must have already felt toward the, for him, insufficiently progressive Third International), he spoke of a “fifth International” as holy.

Note also “holy the Angel in Moloch!” Once again, we see the dialectic of Heaven and Hell, of angels and devils, and of nirvana and samsara. Similarly, the sea and the desert are holy, visions and hallucinations are holy, miracles and the abyss are holy, and “forgiveness! mercy! charity! faith!…suffering! magnanimity!” are holy.

Finally, the “intelligent kindness of the soul!” is holy.

VI: Conclusion

What makes “Howl” a great work of literature, like any great literature, is its embrace of the All. The dialectical unity of opposites is a kind of shorthand for expressing the universal in its infinite complexity. Such merisms as “the heavens and the earth” or “good and evil” are unions of opposites as a quick way of including everything between them, like the eternity of the cyclical ouroboros. The unified Heaven and Hell of “Howl” thus include everything between them, too.

Howling is holy, and vice versa.

You must be logged in to post a comment.