Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was the father of psychoanalysis. He was born in the Moravian town of Pribor, then part of the Austrian Empire, now part of the Czech Republic. While he certainly didn’t invent the idea of the unconscious mind, he created a kind of road map, as it were, for navigating the unconscious; and the resulting insights have made him one of the most important psychiatric thinkers of the twentieth century, influencing art, literature, and film.

Here are some famous quotes of his:

“The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” —The Interpretation of Dreams

“A person who feels pleasure in producing pain in someone else in a sexual relationship is also capable of enjoying as pleasure any pain which he may himself derive from sexual relations. A sadist is always at the same time a masochist.” —Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality

“Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness.” –Letter to an American mother’s plea to cure her son’s homosexuality (1935)

‘The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is “What does a woman want?” –said once to Marie Bonaparte; Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (Hogarth Press, 1953) by Ernest Jones, Vol. 2, Pt. 3, Ch. 16. In a footnote Jones gives the original German, “Was will das Weib?“

“It is easy to see that the ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world.” —The Ego and the Id

“What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books.” –Letter to Ernest Jones (1933), as quoted in The Columbia Dictionary of Quotations (1993) by Robert Andrews, p. 779

I: Early Years

Freud was immensely learned, being proficient in many languages, including German, Hebrew, classical Greek and Latin, English, Italian, Spanish, and French. He could actually read Shakespeare in the original English…from a young age! Indeed, Shakespeare’s insight into human nature influenced Freud, who interpreted much in Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, and other plays. Other writers to have a strong influence on Freud were Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche.

He graduated with a medical degree, but never practiced internal medicine. Instead, he studied cerebral anatomy, neurology, neuropathology (on which he was a lecturer from 1885 to the beginning years of the 20th century), cerebral palsy, and he even did investigations to find the location of the sexual organs of eels (!).

His research into neuropathology led to him trying to help patients with ‘nervous illness’ (neurosis). He went to Paris to study and attend demonstrations of hypnosis by Jean-Martin Charcot. Impressed by its apparent effectiveness in treating hysterical patients, Freud tried hypnosis on several hysterical patients of his during the 1880s, the most famous of whom was “Anna O,” who called Freud’s particular application of hypnosis, involving her speaking while hypnotized, the “talking cure.” He published his Studies on Hysteria with his colleague of the time, Josef Breuer.

II: Free Association

He found, however, that hypnosis didn’t seem to effect a lasting cure for hysteria or neurosis, so he began to devise his own method called free association. He could have the patient lie supine on a couch, thus relaxing the patient to the point of being in a state comparable to hypnosis, which would allow the patient’s unconscious mind to be open and accessible to the therapist. Freud would then tell the patient to speak of anything on his or her mind. There would be no rules at all: the patient just had to talk and talk. There was no need to censor subject matter considered rude, sexually inappropriate, or in any way ‘irrelevant’; in fact, it would be necessary to include such talk, for this would give the therapist free flowing access to the patient’s unconscious mind.

As the patient continued talking and talking, however, he or she would sooner or later hit a wall, as it were, and stop talking. Sometimes this was because the patient knew an anxiety-causing subject was coming dangerously close to being discussed; at other times, the patient simply didn’t know why no more subject matter could be thought of, to continue the chain of associations the therapist was writing down and linking together by way of recurring themes spotted. In the latter case, Freud would assume that anxiety-producing subject matter was being repressed, deep down in the unconscious, so while the patient didn’t know why he or she couldn’t continue, Freud could link together the recurring themes of everything talked about, then speculate on what the cause of repression might be.

One early theory Freud had was called the seduction theory. He found that a lot of his patients were describing sexual relationships with their parents, so he assumed they’d been sexually abused as children, and that this had caused their psychological problems. As it turned out, the sheer proliferation of so many cases of apparent child sexual abuse, as well as his own self-analysis, caused Freud to change this theory into that of the Oedipus complex. Some think he fabricated this new theory to save his career and avoid dealing with the wrath of a mass of parents implicated as child molesters, but such speculations are far from proven. If changing from the seduction theory to a theory of infantile sexuality was meant to improve his reputation among a prudish Victorian audience committed to the belief in the innocence of childhood, Freud chose a very strange way to improve his standing.

III: Dreams

Another method Freud used in mapping out the unconscious mind was dream analysis. Fortunately for the sake of his research, he had made a habit of recording his dreams in journals from childhood, so when he began analyzing himself, he had lots of dreams for material to work with. From his research of his own dreams as well as those of his patients, he produced his first great work, The Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1899, but with the year 1900 printed on the title page, to usher in the twentieth century. In this seminal book, he theorized that all dreams, without exception, even nightmares, were forms of wish-fulfillment.

Now, it is easy to see how having a dream about making love with an attractive partner, or about winning millions of dollars in the lottery, can be wish-fulfillment, but how can anxiety-causing dreams be? Here, we must take into account conflict in Freudian psychology. In our minds, part of us wants to do or have one thing, another part of us wants something contradictory to the first, and we mentally battle it out to see which instinctual drive wins out. When these conflicts become too difficult to reconcile, anxiety results, and this unease can be reflected in the dream content. Hence, nightmares can be an attempt at the fulfillment of contradictory–and anxiety-producing–wishes; they can thus simply be a failure of the dream to sustain sleep.

Let us imagine, for example, a young man who–though he sees himself as heterosexual, nonetheless has repressed homosexual feelings for his handsome male doctor. His urges are so repressed that he isn’t even consciously aware of them, so shocking would they be if ever revealed. Still, he has an odd habit of feeling so chronically ill that he must see his doctor for regular checkups. Now, in his dreams, he probably wouldn’t see himself in bed with the doctor, for this would make him wake up bathed in sweat; for after all, the purpose of dreams is to ensure restful, uninterrupted sleep.

If, on the other hand, the young man dreamed of getting naked for his doctor in a physical examination, his wish fulfillment could thus be indirectly realized, by way of associative compromise; or he could symbolically fulfill his unconscious wish by dreaming of his handsome doctor putting a phallic tongue depressor in his mouth, or a shot from a needle in his behind. There is much distortion of conflicting wishes in dreams, hence their strangeness; and the distortion can reconcile the conflict in a way that facilitates sleep.

But guilt and anxiety from such wishes, especially guilt imposed by an intolerant society, may require a ‘wish’ to be somehow punished or shamed for having these taboo desires. Hence, in his dream, the naked young man, during his examination, may see the door to the examination room suddenly swing open, and all his family and friends outside see him. Or the tongue depressor may be put too deep inside his mouth, causing him to gag or choke; or the shot from the needle may be especially painful. Thus, an anxiety-causing dream fulfills taboo wishes–if only indirectly and symbolically–and also satisfies the wish to alleviate guilt by providing some form of punishment. And the anxiety-causing nature of the ‘punishment’ results in a failure to sustain sleep–the dreamer wakes up from a nightmare.

Apart from Freud’s ideas about dreams as wish fulfillment, and the distortion of dreams, he also touched on such ideas as penis envy and the Oedipus complex. This latter idea is dealt with in a special way, through his analysis of perhaps the two greatest tragedies in Western literature, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Why is any work of art considered great? Because it communicates ideas we can all relate to in some way, and Freud believed these plays to fulfill a man’s deepest unconscious fantasy: to be rid of his father and to have his mother.

In Oedipus Rex, the title character has directly, if unwittingly, fulfilled this wish, and the tragedy of the play comes from his horror and shame in realizing he has murdered his father and married his mother. In the case of Hamlet, the fantasy is fulfilled vicariously by Hamlet’s uncle Claudius, and Hamlet delays his revenge because he unconsciously understands that he is no better than Claudius. So he can’t bring himself to kill his uncle. Productions of Hamlet throughout the twentieth century portrayed the Danish prince as having a thing for his mother.

IV: Errors and Humour

Freud’s next book was The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. In this book, he theorized about the psychology of errors. Slips of the tongue or of the pen, or mistakes of any kind were, in Freud’s opinion, not mere accidents: they expressed unconscious wishes. Again, conflicting instincts in the mind–part of us wants to do something, another part of us doesn’t want to do this thing–cause us to resolve them by ‘half doing’ things, or doing them incorrectly. Particularly amusing slips of the tongue, ones whose unconscious meanings are obvious, and often sexual, are called “Freudian slips.”

Let me tell you an amusing story.

Back in about 1997, at the English cram school where I was teaching Taiwanese kids, I had a habit, well known among my coworkers, of eating late lunches at the local Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) before teaching my later afternoon and evening classes. One afternoon, I was outside the school, about to get something to eat, and I was chatting with an attractive young female Taiwanese teaching assistant. Her English was reasonably good, but she made errors in grammar here and there. During our brief chat, we were being flirtatious. Our chat ended, and I was about to leave. She said, “So, are you going to FCK now?”

Speaking of humour, another book Freud wrote around this time (early 1900s) was Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious. In this book, he wrote of how all the jokes we tell reflect unconscious desires.

V: Stages of Psychosexual Development

Now, one of Freud’s most controversial ideas, particularly shocking during the prudish Victorian era, were his theories about childhood sexuality. These ideas were dealt with in such writings as the Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and “The Dissolution of the Oedipus Complex,” among others.

The stages of psychosexual development have a child going through polymorphous perversity, when a child can be aroused by virtually anything, or have anything be an object to satisfy his libido, no matter how bizarre, since so young a person hasn’t yet been taught by society to focus his or her sexual energies on ‘acceptable’ objects.

The first of these psychosexual stages is the oral stage, during which an infant or child gains pleasure from sucking or biting on things. Obviously, it is connected with the years when a baby is breast-fed. If a person, however, is fixated on the oral stage later in life, he or she may express this fixation through such habits as smoking. In light of Freud’s insight into such matters, it is astonishing how he, a lifelong smoker of cigars (which eventually gave him cancer of the jaw), wouldn’t give up his habit.

The next stage is the anal stage, when a child derives pleasure from defecating. This is linked to a child’s potty training. If one is fixated at this stage, and becomes anal retentive, one might develop the following personality traits: excessive cleanliness, parsimony, fastidiousness, stubbornness, and a need to be in control. As Freud theorized in his paper, “Character and Anal Erotism,” one opposite may shift to the other (i.e., from filthy defecation to neat and tidy cleanliness and fastidiousness, through reaction formation); or preoccupation with this unclean state may be expressed associatively (i.e., filthy feces symbolized by a love for filthy lucre, hence, parsimony).

Next comes the particularly controversial phallic stage, when little boys and girls discover a certain anatomical difference between them, resulting in the castration complex. Imagine, for example, a five-year-old boy and his four-year-old sister taking a bath together for the first time. Their mother is getting the bath ready, and the boy and girl, naked, are facing each other, noting the difference between them.

Now imagine the boy’s reaction when he sees his sister, without a penis, but a slit in that place instead. The slit seems to be a wound: has she been castrated? With his Oedipal longing for Mommy and wish to dispose of Daddy, the young lad imagines his sister’s ‘castration’ has been her punishment for also wanting to take Mom away from jealous Dad. Now, the boy realizes Dad may want to castrate him, too, for having the same Oedipal urges. The fear that the boy has is called castration anxiety.

Castration anxiety has a profound effect on a boy’s psychological development, according to Freud. It finds symbolic expression in a man’s fear of being humiliated, especially if this involves, for example, losing an argument with a woman. After all, if women are just ‘castrated men’ in his eyes, then he will often have “an enduringly low opinion of the other sex [i.e., women],” as Freud said in a footnote, added in 1920, to the second of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Here, Freud is merely commenting on the reality of sexism: for what seems to be his agreement with sexism, read on…

For the girl’s version of the castration complex, the idea especially detested by feminists, Freud called it penis envy. Imagine again the naked boy and girl in the bathroom. When she sees the dangling members on him that she lacks, she feels “unfairly treated,” as Freud argued in his essay, “On the Sexual Theories of Children” (1908). Why is she deprived of what he has?

Her resulting resentment–coming after a period of denial during which she, for example, attempts urinating while standing (her brother, too, at first denies her ‘castration,’ imagining her ‘penis’ is just really small, and will grow larger later)–causes her to feel a generalized jealousy, which Freud, in his 1925 essay “Some Psychical Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction Between the Sexes,” called a “displaced penis-envy.” Some of this, Freud believed, resulted in feminism. It also results, apparently, in women having, on average, relatively weak superegos.

Here, Freud’s sexism reached a particularly low point, since even though, in the aforementioned 1925 essay, he would “willingly agree” that most men fall far short of the masculine ideal, and that there is much psychic bisexuality in the personality traits of both sexes, and thus pure maleness and femaleness are socially constructed ideas “of uncertain content,” the historical, worldwide male denunciations of women’s inferior moral sense are, it seems, justified (!).

For feminist defenses of Freud, one can look to the writings of Juliet Mitchell (in particular, her 1974 book Psychoanalysis and Feminism: Freud, Reich, Laing, and Women) and Camille Paglia (she brings up Freud, the unconscious, and the danger of ignoring these ideas about 15 minutes into this video. Here’s another, around 6:30 into it.)

Now, with the bringing on of the castration complex, another difference between the sexes arises: the boy’s Oedipus complex ends–or is, at least, repressed–out of the fear of the father’s retribution, replaced by identification with him; and the girl’s original Oedipal love for her mother, out of a belief that Mom castrated her, switches to a new Oedipus complex, hers being a love for her father and a hatred for her mother. Carl Gustav Jung called this the Electra complex (a term Freud scoffed at), also based on Greek myth; for Electra hated her mother, Clytemnestra, for plotting with her lover, Aegisthus, to murder Agamemnon, Electra’s beloved father.

With this new Oedipal attachment, girls apparently long to possess their father’s penis, and as they grow up, this desire to have that “little one” gets displaced, and the desire to have another “little one,” a baby, is supposed to come about in womanhood. This verbal relationship between penis and baby, both called “das Kleine,” or “little one,” is described in Freud’s 1917 essay “On Transformations of Instinct as Exemplified in Anal Erotism.”

When the phallic stage is over, a period of lack of interest in sexual matters, the latency period, occurs from roughly the age of five or six until the onset of adolescence. Then the sexual instincts reawaken, and if no fixation during any of the earlier stages has occurred, teenagers should have attained the genital stage, in which they derive pleasure from the genitals, a state of affairs considered normal and mature. Along with this notion of sexual maturity, Freud insisted that a woman’s orgasms should be vaginally based; orgasms based on the clitoris, apparently, are sexually immature (!).

VI: The Theory of the Personality

According to Freud, we all begin with the id (Das Es, ‘It’). This ‘thing,’ this primitive, selfish, savage animal inside us is on an endless quest for gratification. It operates on the pleasure principle, which, put bluntly, says, “If it makes you feel good, do it.” It is like a naughty, bratty, spoiled child, constantly demanding the satisfaction of its urges.

Imagine a little boy who hasn’t developed a sense of restraint yet. The cookie jar in the kitchen is within his reach. Without even a second’s consideration of the consequences, he impulsively grabs all the cookies he can eat and munches away. Then Mom catches him, and he gets a spanking.

Having learned his lesson, the boy begins to develop an ego (Das Ich, “I”). His id is pushed somewhat into his unconscious, and his ego operates on the reality principle, which is a modification of the pleasure principle, saying, “If it makes you feel good, do it, but only if it’s safe.” Now if he wants to steal from the cookie jar, he must make sure neither Mom nor Dad catches him; if both are totally distracted by the TV in the living room, and if he doesn’t eat so many cookies that his parents know some are missing, he should get away with his act of petty larceny. If his parents suspect that some cookies are unaccountably missing, perhaps he can blame the theft on a younger sibling!

So far, our boy still hasn’t learned about morality, but he will, from all the authority figures in his life: his parents, teachers, religious leaders, etc. When he has learned about right and wrong, he has a superego (Das Uberich, “Over-I”), which demands that all his thoughts and behaviour conform to an ego ideal, or perfect standard of morality. Now, whenever he is tempted to take a cookie or two from the cookie jar, not only does he have to avoid being caught, he has to wrestle with the guilt of knowing he is selfish and inconsiderate to his family. Perhaps he is fearful of God watching down from heaven with a disapproving frown!

His id has now been repressed deep down into his unconscious; parts of his ego and superego, like an iceberg, are submerged down there, too; part of those two are also in the preconscious, which is just under the surface, and whose thoughts are accessible to the conscious mind. And now the ego must act as mediator, managing the conflicting demands of libido, reality, and morality. How can the ego do this?

VII: Ego Defence Mechanisms

Fortunately, the ego has a number of defence mechanisms, which aim to reduce anxiety and guilt. We have already encountered a few of these, including these two: repression, which pushes unacceptable urges deep into the unconscious, so one doesn’t even know one has such feelings; and displacement, which moves one’s instincts from an unacceptable object to an acceptable one.

Imagine a man being yelled at by his boss in a manner that’s left him feeling humiliated. He cannot direct his rage at his boss, of course; so when he goes home, fuming inside, he looks for an excuse to blow up at his wife (bad cooking, nagging at him, etc.) or at his kids (playing too loudly, not doing their homework, etc.).

A special kind of displacement is called transference, which involves, for example, displacement of a patient’s feelings (romantic love, hostility, etc.) onto his or her therapist. When, for example, some of Freud’s female patients began falling in love with their therapists, at first he found the transference a discomfiting distraction from the psychoanalytic task at hand; later, he found it useful to work with the transference as part of the journey to find a cure for the patient’s neuroses.

Along with transference comes countertransference, when the therapist develops feelings for the patient. Freud recoiled at this returning of feelings, fearing that an emotional involvement with the patient was unprofessional and damaging to the cool, scientific rigour of psychoanalytic investigation; but later analysts, such as those involved in object relations theory, found good uses for countertransference, feeling that it could simulate, and thus regenerate, relationships stifled in their patients’ childhood, a stifling caused by bad parenting.

Other ego defence mechanisms include suppression, a restraining of instincts, but allowing them to remain conscious. Also, there is denial, whose guilt-relieving mechanism is self-explanatory; and projection, where one throws one’s anxiety-causing instincts onto others, blaming them instead of oneself for the fault. For example, I could accuse others of being rejecting of me, when actually it is I who am being rejecting of them. Rationalization, using excuses to justify unacceptable acts or desires, is another defence mechanism.

Yet another ego defence mechanism is reaction formation, where one creates a contrived reaction that represents the opposite attitude to one’s real, and guilt-causing instinct. A perfect example is in the movie American Beauty, in which a retired marine (played by Chris Cooper) expresses the most hateful bigotry against homosexuals throughout the film; but near the end, he reveals that he himself has suppressed homosexual feelings when he kisses the protagonist (played by Kevin Spacey) on the lips.

One particularly interesting ego defence mechanism is sublimation. Instead of the more usual, hypocritical defences, this one is actually quite positive in nature, for it redirects unacceptable impulses into creative outlets. Homosexual Michelangelo’s paintings and sculptures of muscular naked men are a case in point.

Freud’s daughter Anna would develop and see more importance in ego defence mechanisms in her work, especially in her classic work, Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (1936). The significance of the unconscious portion of the ego means that in therapy much ego defence is unconscious, so the analyst mustn’t focus only on bringing out id impulses. Hence, the origin of ego psychology.

VIII: Life and Death Instincts

For much of Freud’s career, he felt that the instinctual drives were all pleasure-based (libido), and sexual in nature. This is part of the life instinct, also called Eros.

After the horrors of the First World War, however, his thinking about human nature took a darker turn, and would remain essentially thus for the rest of his life (the excruciating pain of his cancer wouldn’t help lighten things up much). In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud discussed the more destructive side of human nature, and postulated a death instinct (Thanatos would be the word used, though not by him). This would explain our aggressive and self-destructive sides, as well as our tendency to do the same irrational things over and over again (“the compulsion to repeat“).

All forms of pleasure, whether sexual or death-oriented, involve putting the body into a state of rest. The cliché of a man and woman in bed after great sex, with him rolled over and fast asleep, and her smoking a cigarette, show how Eros (in this example, in the form of libidinal gratification) leads to a restful state. As for Thanatos, there is no more absolute a state of rest than death. As Hamlet said, “To die, to sleep–/No more; and by a sleep, to say we end/The heartache and the thousand natural shocks/That flesh is heir to, –’tis a consummation/Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep…” So here, the achievement of self-destruction in a nightmare can be seen as an exception to the idea of all dreams as pleasure-causing wish-fulfillment.

IX: Religion

Freud was born a Jew, but was also an atheist. He believed that God represents the psychological need many of us have for a father figure. His two major writings on religion, generally discredited since anthropology was not a field he specialized in, were Totem and Taboo, and Moses and Monotheism. The former dealt with primitive taboos against incest, as well as with Freud’s belief that the killing and ritual eating of the primal father was common in primitive tribes; and in the latter, Freud theorized that Moses was an Egyptian adopted by the ancient Hebrews, who later killed him (this being a reiteration of his theories in Totem and Taboo), then by way of reaction formation assuaged their guilt by revering him as the founding father of their religion.

X: Post-Freud

As previously mentioned, his daughter Anna carried on the torch, with her focus on ego defence mechanisms. Along with her among the Ego Psychologists was Heinz Hartmann, who focused on how the mind adapts in an evolutionary sense, rather than merely from psychic conflict and frustration. Given the right environment, a child’s intrinsic potential for adaptation will help it adjust to the demands of the real world, an adaptive development that needn’t be conflictual.

Then there was object relations theory, which explains how problems in adult relationships can be traced to problems in the parent/child relationship. Famous thinkers in this school include D.W. Winnicott, W.R.D. Fairbairn, and Melanie Klein, with her concepts of the good breast, which nourishes and brings out love, and the bad breast, which doesn’t feed or do any good for the infant, causing it to feel hostility instead. Her ideas about projective identification expand on Freudian projection to show how a patient can make his projections become real in other people. Her ideas were quite a break from Freud, though she considered them perfectly consistent with him.

Heinz Kohut, with his conceiving and development of self psychology, did much research and gained much insight into narcissism and NPD.

Jacques Lacan saw himself at one with, even returning to, Freud. Lacan’s notion, for example, that “the unconscious is structured like a language” was in part derived from Freud’s ideas about slips of the tongue and jokes as expressions of the unconscious. Lacan’s ideas have greatly influenced postmodernism, poststructuralism, critical theory, feminist theory, and such contemporary thinkers as Slavoj Zizek.

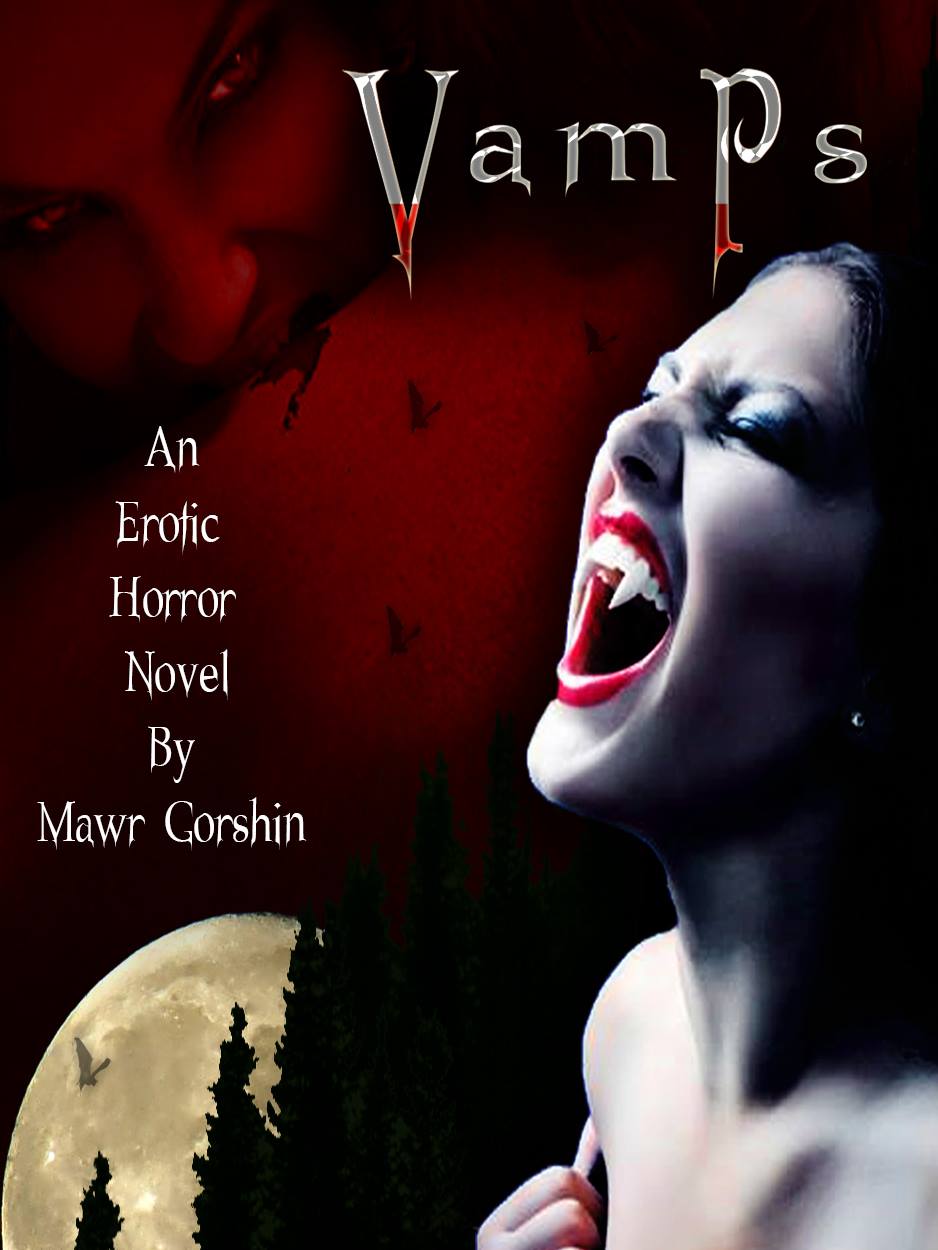

Here is a link to my vampire erotic horror novel, ‘Vamps.’

Here is a link to my vampire erotic horror novel, ‘Vamps.’

You must be logged in to post a comment.